“Not only does the COVID Alert app keep you safe, but it’ll also slow the spread of the virus and help prevent future waves,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted two months after the long-anticipated COVID Alert app was made available on iOS and Android.

Nations across the world took a similar approach, collectively thought of as a way to break down the cycle of COVID-19 infection.

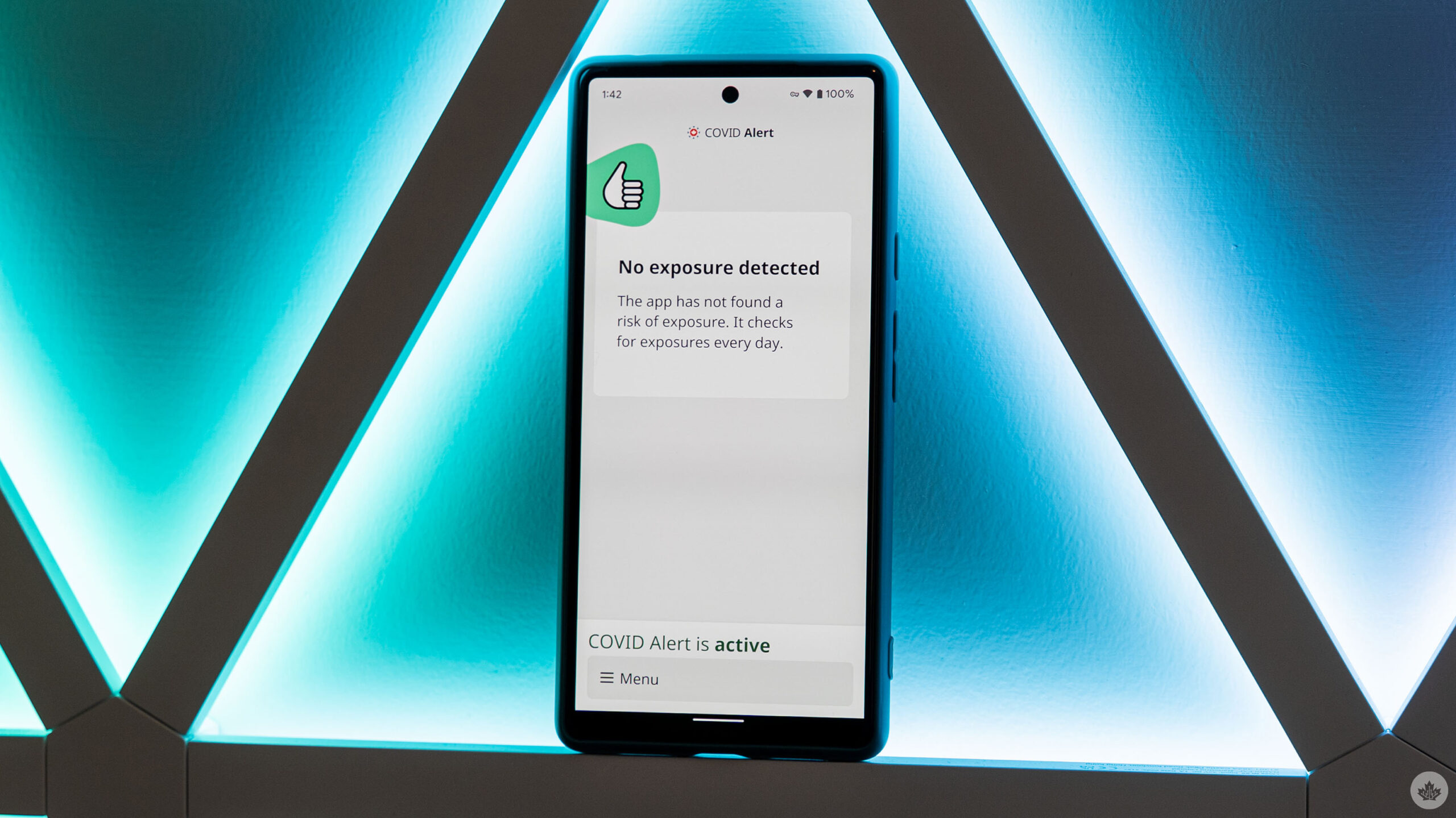

The app was presented with the idea that no personal data would be collected. Instead, a low-energy Bluetooth feature detects proximity with other phones and exchanges random codes.

After Canadians test positive for COVID through a PCR test — which have become increasingly rare — they receive a code to upload. Those who spend 15-minutes near another user who has tested positive and uploaded a code will be alerted.

But a year-and-a-half after Canadians downloaded the COVID Alert App, questions started to emerge if the app was useful anymore or if it even served its initial purpose to begin with.

The numbers

As of February 1st, the COVID Alert app was downloaded nearly 6.9 million times across nine provinces and territories in Canada. Local governments in Alberta, British Columbia, Nunavut and Yukon didn’t make the app available to their residents.

According to 2016 census data from Statistics Canada, the collective population of residents 15 and older for all the provinces and one territory where the app is available equals just over 22 million. This means only 31 percent of Canadians 15 and older who had the app available to them downloaded it.

Of course, there are several factors impacting this. Not everyone has a phone or applicable service that can allow them to download the app in the first place. The app also wasn’t available to all Canadians at the same time and depended on when local governments launched it in their province or territory. Provinces started to adopt the app in October 2020.

But that didn’t mean everyone who received a code uploaded it.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford promotes the app in a video. Image credit: Doug Ford/Twitter

Figures shared with MobileSyrup show that between October 2020 and January 2022, a total of 57,615 codes were uploaded. Data shared by Health Canada indicates a total of 81,434 codes were issued to the one territory and eight provinces that participated in the app. It’s unclear how many people could have been informed if codes were actually uploaded.

The government spent $21 million creating and promoting the app. Google and Apple worked together to create the foundation of the app.

Health Canada told MobileSyrup they don’t track how many people deleted the app.

“Bad Policy”

Blayne Haggart, an associate political science professor at Brock University, told MobileSyrup ‘technological solutionism’ is at play. The concept refers to looking into how technology can deal with a problem instead of exploring what the best method may be to deal with the issue.

“It wasn’t so much this is the best way to improve contact tracing, but it’s here’s how we can use technology to improve contact tracing,” he explained. “In doing so, it actually changes what is meant by contact tracing in a way that I don’t think was particularly helpful.”

Referring to academic research by Tamar Sharon, Haggart explained contact tracing requires information that can turn into a possible data point. In the case of the COVID Alert app, the obligation starts and ends with phones being in contact with each other for more than 15 minutes with the idea that a lot of information on whereabouts and personal information is kept safe and not shared with the government.

But Haggart said contact tracing, especially when done manually, depends on trust and taking a deep dive into contact with others. The digital app can’t pick up on other factors that may prevent the spread of the virus, like if people were in a well-ventilated room when they came into close contact or had a barrier between them.

“It basically took contact tracing, which is quite a complex and involved process, and turned it into a couple of data points, which themselves may or may not be accurate, depending on the quality of the technology.”

The chart below shows where codes are issued. PEI and North West Territories are represented in “other” given less than 20 codes were issued each.

Technology is not a one size fits all solution. The app is designed to keep information private, but that "limits its utility in a public health context."

There isn't a lot of trust between government and tech companies when it comes to data and surveillance and there were a lot of questions on privacy and how data would be used. Given how important trust is in contact tracing, Haggart said that should've worked as a warning that maybe this app wouldn't work very well.

"It was based on the idea that you can deliver this public service without having to trust anybody."

In a way, the onus was put on the public to be their own contact tracers and take charge of COVID since they were responsible for downloading the app, requesting and uploading codes themselves.

MobileSyrup asked Health Canada if a specific threshold would deem the app ineffective but didn't get a direct answer.

"The Government of Canada continually reviews the evolving scientific evidence and public health guidance to determine the app's continued use. The Government of Canada is maintaining and monitoring the service as the pandemic evolves," a spokesperson said.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.