Welcome to Tête-à-Tête, a series where two of our writers converse on interesting topics in the mobile landscape — through chat. Think of it as a podcast for readers.

This week, Daniel and Douglas chat about whether bringing cellular service to the underground spells doom for the calm commute.

Daniel Bader: Douglas, you charming man, I like talking to you. I like those times when conversations sprout from nothing, a wending trail of topics leading somewhere — or nowhere.

But I also like to not talk. I like to have that option.

With the announcement that Montreal’s Metro Service, STM, have begun rolling out cellular service to one of its lines, and T-Connect, Toronto Transit Commission’s wireless infrastructure, is all set for carriers to roll out signal in the coming years, the truth is this: we’re soon going to have nowhere to hide from the hoards of cellphone-clutching close talkers.

Thinking about this, I’m excited about the potential for getting work done while traversing Canada’s various underground transit systems, but, like that of cellular service on planes, the inevitably close proximity to people making phone calls sours somewhat my enthusiasm.

What do you think: is the tradeoff worth it? And since wireless signal regulation doesn’t exist on public transit systems, is opening up cellular service to underground commuters a Pandora’s Box of frustrated, underslept people trying to catch some early morning shuteye?

Douglas Soltys: Daniel, don’t kid yourself. Firstly, the subsurface cellular expansion has nothing to do with productivity: it’s so people can check Facebook and Instagram, watch YouTube videos, and fire off a few Snapchats on their commute home. In the same way that the ability to bring a book on the subway doesn’t prevent people from choosing Dan Brown over Hemingway, cellular access won’t magically make commuters more productive, just more connected.

Which is a shame, because like you, I too value the imposed digital silence of the Bloor line. While I might have my earbuds in listening to music or a podcast, at least I’m not staring compulsively staring at a screen like every other moment of my day (seriously, if you know the strength of your particular mobile addiction, download Checky and weep). It’s a moment of respite, when I actually see my fellow commuters, and sometimes even pause to consider an existence outside my own.

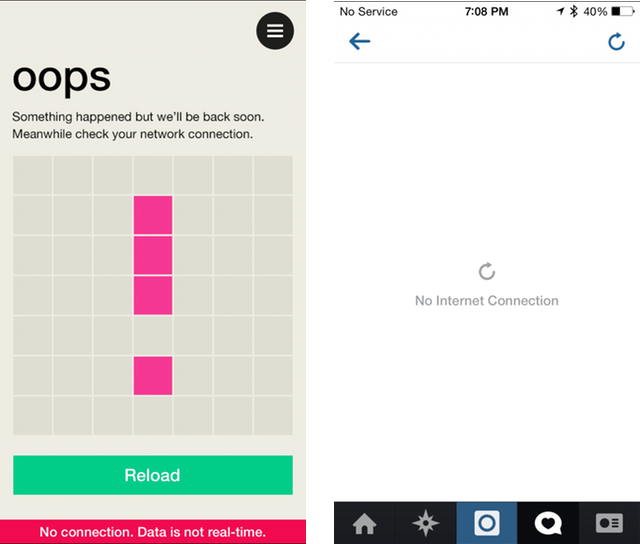

But as you said, ubiquitous connectivity in inevitable, and resistance is futile. So let’s make this conversation more productive, and consider the quality of this service. So far, I’ve been remiss to use T-Connect, not only because of its limited station support, but because I hate the idea of being forced to watch one more low-grade video ad just to get to my ad-filled Facebook feed. There’s a difference between cellular service and good cellular service, and I’m wondering if you think we can expect the latter.

Daniel: The beauty of underground cellular connectivity is that it will be exactly that — cellular. It won’t require a splash page or a terms of service: it will be your existing SIM card communicating with your existing provider.

And while WiFi on the platform is step one of a three-step process (cellular on the platform being the next one), eventually we’re going to be connected everywhere. There’s something to be said for being comfortable going offline, but when I used to live north of Finch, I’d lose a lot of time not working. That said, I agree with you: few people are going to take advantage of those available megabytes to collaborate on a Google Doc — and even today, those people can take the document offline and sync it later — but I’m talking of advantage in a broader sense.

You see it today: when the subway emerges from its dark tunnel into the light of day (or early winter evening), people clamber to check messages, make calls (“Come pick me up, I’m at Rosedale!”) or update Twitter before the subway continues on its underground journey. Removing the load from those towers will not only make the experience better for everyone in the surrounding areas, but it will ensure that riders have a better time riding, which is what public transit is all about. An essential service facilitating another essential service.

But few people want to overhear someone’s phone call during a morning, and some people even prefer to be offline for those precious, quiet minutes. Do you think there’s something to be said for forced disconnection?

Douglas: It’s funny: when I read that the first time, I thought you wrote ‘forced discretion.’

I think we live in a society that rightly expects certain freedoms, but rarely pays attention to the responsibilities that coincide with those freedoms. I think we’re past the point where most people desire, let alone expect, to disconnect in major metropolitan areas. As such, any forced disconnection will be seen as either a violation or an impediment, but not really an opportunity.

Look at us, two tech reporters hoping for peace and quiet rather than constant connection. Why is that? Perhaps as more and more devices and product categories find new ways to keep us connected, we’re looking for a filter to only let in what we really need or want? I’ll accept constant connectivity whole-heartedly the day Siri/Cortana/Her is smart enough to act as my personal assistant/receptionist/digital body guard.

Daniel: That’s exactly it: discretion is key to delivering a network of connected humans. Just as we give a strange look to someone talking into an invisible microphone on the street, text-based communication has risen in popularity. Canadians send more texts than any country in the world, and we love our WhatsApp, Kik, Facebook Messenger and BBM. We are a country of polite talkers, and I would hope, given the opportunity, we’d continue to do so on the subway — or anywhere with an LTE signal.

Image Credit: Urban Toronto

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.