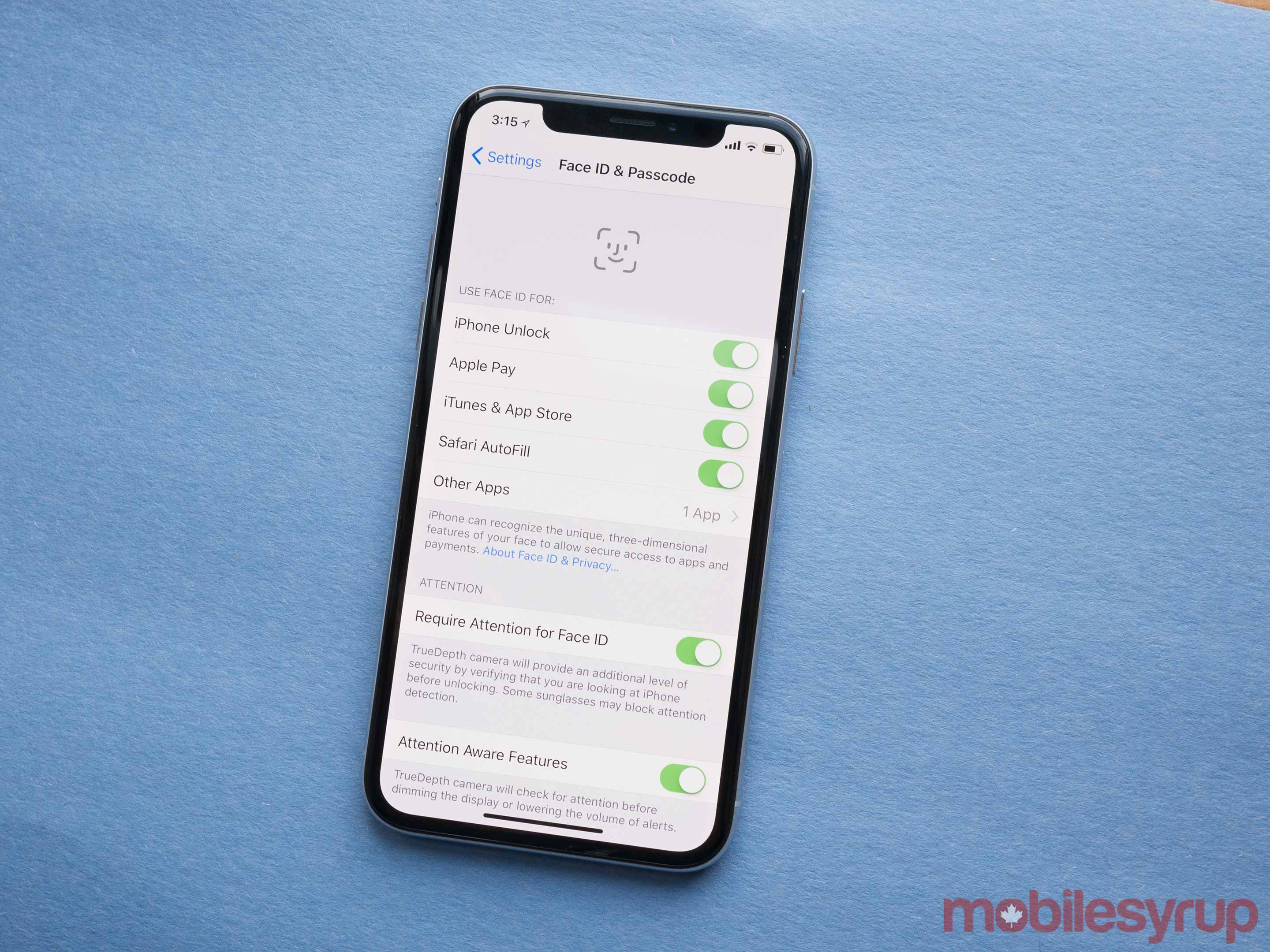

At its core, Apple’s Face ID is a facial scanner that unlocks the iPhone X when the device recognizes the user’s face.

You no longer need to press your finger against a fingerprint sensor — like with Touch ID — and users don’t need to type in a password — like with locked computers or smartphones. All it takes for the owner of an iPhone X to unlock their smartphone is to raise the device to their face, allow the phone’s TrueDepth camera to scan their facial features, and briefly wait for the device to unlock.

Apple claims that the process is almost instantaneous and that there’s a one-in-one-million chance that someone else will be able to unlock the phone using their face. Apple has also reassured any potential owners that Face ID can’t be fooled by a photograph, like other similar features that currently exist in the market.

In a recent security briefing, Apple clarified that the iPhone X’s facial recognition biometric data is not stored in the cloud. Instead, facial data will be kept onboard the iPhone X’s A11 Bionic chip — meaning that Apple won’t be able to use any user’s biometric data without their consent.

Apple has further clarified that you can disable Face ID by pressing a number of different button combinations — the easiest of which is holding down the device’s right-side button along with the volume down key.

These facts are meant to alleviate concerns related to losing the phone, as well hesitancy related to switching away from Touch ID — biometric technology that arguably led to the widespread adoption of fingerprint sensors on modern smartphones.

While comforting, Apple hasn’t actually addressed the larger privacy concerns raised by the presence of their facial scanner on the iPhone X — namely that privacy legislation currently doesn’t outline any specific rules stopping government actors from abusing software that automatically unlocks a phone as soon as the device recognizes its owner.

As a matter of fact, there’s very little privacy legislation outlining any specific rules about fingerprint sensors and other biometric security measures, either. That’s the central problem, and in Apple’s defence, there’s very little that the company can do to actively change Canada’s, or the U.K.’s, or even the U.S.’s privacy legislation — which was outdated when Touch ID launched on the iPhone 5S in 2013 and that has changed very little since then.

Canadian law enforcement addresses the legality of warranted and warrantless searches

In Canada, law enforcement at any level — whether municipal, provincial or federal — is beholden to the existing legal infrastructure established by the laws of the land (including acts of Parliament), case law and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The RCMP, therefore, “allows for search of material relevant to the investigated offences only.”

According to an RCMP spokesperson, Canada’s federal police force also “uses a search warrant to access data on lawfully seized devices.”

This falls in line with Section 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which clearly outlines that “Everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure.”

It’s right there in the Charter’s text, immediately following Section 7’s establishment that “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person… in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” The RCMP clarified that there are a number of circumstances by which the force “may conduct a search of a personal item contained within a prisoner’s personal effects, including a prisoner’s wallet or cellphone” — including a search without a warrant in circumstances when a search is incidental to arrest.

The RCMP clarified that there are a number of circumstances by which the force “may conduct a search of a personal item contained within a prisoner’s personal effects, including a prisoner’s wallet or cellphone” — including a search without a warrant in circumstances when a search is incidental to arrest.

To be clear, the RCMP is allowed to search material that is deemed relevant to the investigation at hand. This can include things like a person’s home, car and, of course, their electronic devices.

“Such a search must be done promptly upon arrest or as soon as practicable after arrest, i.e. with proper justification it can be conducted in cells,” explained an RCMP spokesperson, in an email exchange with MobileSyrup.

The RCMP can also search devices without a warrant if “reasonable grounds exist to obtain a warrant to search an item, yet the delay necessary to obtain a search warrant would result in danger to human life or safety (including the prisoner’s), and/or loss, destruction, disappearance or removal of evidence.”

Admittedly, that’s a very complicated statement. In short, the RCMP is allowed to search electronic devices without a warrant if it makes sense to search an electronic device, but waiting to get a warrant could endanger someone’s safety or ruin evidence.

“…there exists no legislative compulsion to force a person to unlock their phone for police.”

Obviously, the RCMP can also search an electronic device if they’re given consent by the legal owner of the device, “which at times may be a person other than the prisoner.”

It’s also important to note that, according to the RCMP, “there exists no legislative compulsion to force a person to unlock their phone for police.”

This means that there’s currently no law in place that compels individuals under arrest to unlock their devices for an officer. That is to say, if asked by the RCMP to provide a password for a locked device, an individual can’t be forced to turn over the password.

However, Face ID isn’t technically a password or passcode.

Theoretically speaking, if RCMP officers felt it was justified to search your iPhone X, it would not necessarily be unconstitutional for RCMP officers to point the locked phone at your face in order to access its contents. After all, are you being forced to unlock your phone if it can be unlocked by simply pointing it at your face?

Then again, Face ID only works if your eyes are open. You could always close your eyes the entire time you’re under arrest.

MobileSyrup also asked if the RCMP takes into consideration the different kinds of biometric security protections on a smartphone before determining how to proceed with the investigation of the device.

The mounted police replied with a single word: “No.”

As representatives of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) and OpenMedia — two Canadian civil rights advocacy groups — will later elaborate, these distinctions matter, because biometric security can be bypassed by the simple DNA that law enforcement collects during routine arrests.

Electronic devices at the Canadian border

Of course, the RCMP wasn’t the only federal agency that has an established position on electronic devices.

According to a Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) spokesperson, anyone trying to enter Canada is beholden to a complete search of any goods they may be attempting to carry into the country. If requested, you have to submit to a CBSA search.

“Electronic devices and media, including laptops, cell phones and other devices are classified as ‘goods’ in the context of the border, and CBSA officers have the lawful authority under Section 99 of the Customs Act to examine them as part of a routine examination,” said a CBSA spokesperson, in an email exchange with MobileSyrup.

Section 99 of the Customs Act enumerates the circumstances in which CBSA officers may search the belongings of someone attempting to cross into Canada. It’s a lengthy section, with multiple subsections broken down into further sub-subsections; however, it’s Section 99.1.a that really matters.

Interestingly enough, the CBSA clarified that Section 99 of the Customs Act doesn’t require the agency to establish reasonable grounds to “suspect or believe that a contravention has occurred.” In this case, the phrase “reasonable grounds” refers to the legal definition of the term, meaning that, once again, the CBSA technically doesn’t need to have a reason beyond suspicion to issue a search.

However, it is CBSA policy that an individual’s electronic devices will only be examined “where there is a multiplicity of indicators, or [to further] the discovery of undeclared, prohibited, or falsely reported goods.”

As for passwords, the CBSA will only “make note of passwords to gain access to information or files if the information or file is known or suspected to exist within the digital device or media being examined.”

“Passwords are not to be sought to gain access to any type of account (including any social, professional, corporate or user accounts), files or information that might potentially be stored remotely or online,” said the CBSA spokesperson.

All of which is to say that, if a CBSA officer asks you to unlock your device, you legally have to comply, but you don’t have to turn over any social media passwords, passwords to email accounts or passwords of any other variety.

“Modern law treats the contents of our phones and laptops […] as no different from the contents of a suitcase.”

It’s also important to note that CBSA policy mandates that a border officer disable a device’s wireless communications during a search. That still doesn’t change the fact that you have to submit to a search if requested.

Crossing into the U.S. from Canada is a completely separate issue, handled by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. However, Privacy Commissioner Daniel Therrien has previously said that Canadians should be “very concerned” about having their digital devices searched at the U.S. border.

Parliament is also currently debating preclearance measures for individuals entering the U.S. via Canada that should more firmly establish the rules for searching electronic devices.

As a quick note, MobileSyrup did reach out to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) in researching this story. However, the OPC was unable to coordinate a phone or email interview.

Biometric security and privacy from the perspective of Canadian civil liberties groups

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) is a not-for-profit organization that works through Canada’s legal system to ensure that the human rights and democratic freedoms of anyone who calls Canada home are secure at all times.

Brenda McPhail has been the director of the CCLA’s privacy, technology and surveillance project since June 2015. She has a masters of information studies in library and information science from the University of Toronto, as well as a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto’s faculty of information.

“…it still is a very unsettled area of law.”

Understandably, McPhail has some noteworthy opinions on digital privacy and, to her credit, when asked about law enforcement authority to compel prisoners to unlock their devices — with or without a warrant — she matter-of-factly told MobileSyrup to consult a defence attorney.

Still, McPhail was able to shed some insight on the subject of Canadian privacy law and biometric security, beginning with the fact that “it still is a very unsettled area of law.”

“In general, fingerprints and other physical biometrics are treated differently in law than a passcode,” said McPhail, in a phone interview with MobileSyrup. “You actually have more privacy protections in the passcode than the biometrics.”

That’s because there’s little Canadian case law on the subject, and according to current precedent established in places like the U.S., biometric data is considered part of an individual’s body.

“Police can, with a warrant when it’s necessary, collect DNA,” said McPhail. This includes DNA like a fingerprint, or a breath sample at an impaired driving checkstop.

“A passcode is a product of your brain.”

In contrast, “a passcode is a product of your brain,” explained McPhail.

“So there are constitutional arguments that you shouldn’t be able to provide a passcode in a confrontation if providing a passcode is giving evidence against yourself,” said McPhail. “[There are] potential arguments to be made around passcodes and protecting passcodes that you can’t make with biometrics with the way jurisprudence is going.”

When McPhail says that there are potential arguments to be made, she means that quite literally. In many cases — both legal cases and the colloquial definition of the term — the important, essential arguments haven’t been made yet, because Canada’s legal framework hasn’t gotten to the point where it seriously needs to start legislating things like passwords versus biometric security on electronic devices.

“Law enforcement has long been behind the times when it comes to addressing the immense privacy considerations that should come with new technology.”

A device like the iPhone X, with facial scanning that Apple claims outrivals anything else on the market, enters a legal framework that isn’t just unprepared — it’s unaware.

Victoria Henry, a surveillance and free expression campaigner for digital rights not-for-profit OpenMedia, put it quite simply.

“Law enforcement has long been behind the times when it comes to addressing the immense privacy considerations that should come with new technology,” said Henry, in an email to MobileSyrup. “Modern law treats the contents of our phones and laptops, which contain everything from our most private conversations and photos to medical records and banking information, as no different from the contents of a suitcase. This is clearly outdated and needs to be addressed.”

Consider a series of thought experiments

Imagine you’re at a family gathering and you put your iPhone X down on a table. You’re with family and you trust them — it’s also rude to be on your phone around the people you love. Your 10-year-old, tech-obsessed cousin picks up your phone without your permission, points the device at your face, and has complete access to the contents of your device. Naturally, you’d be annoyed, but considering that your cousin meant no harm, you let it slide and let the kid play with your phone. Maybe you even politely, but firmly, tell your cousin that it’s rude to take other people’s stuff without asking first. Still, no harm, no foul.

Now, imagine you’re at the Canada-U.S. border, driving back home with your Canadian father and mother after visiting your American aunt and uncle. You approach the Canadian border agent, and they ask you to unlock the contents of your phone. You ask if you absolutely need to unlock your device, and the border agent says that yes, legally you do. Your parents whisper that you should listen to the agent and unlock your phone. After all, it’s not a big deal, right? You have nothing to hide, and they don’t want to run the risk of a lengthier security check — or worse. You unlock your device, and the border agent has complete access to your smartphone.

One last thought experiment. Imagine you’re at a police station, in an interrogation room. As is routine, the officers have taken the contents of your pockets — your wallet, your keys, and your shiny, brand spanking new iPhone X. They ask you to unlock your phone. You’re not smart enough to stay out of trouble, but you do know that under Canadian privacy law, agents of law enforcement need a warrant in order to compel you to hand over a password to unlock your phone.

But then the officers realize that you’re the proud owner of an iPhone X. It’s got a facial scanner. Canadian law isn’t terribly clear about biometric security. The officers confer with one another and determine that, for the sake of their investigation, they’ll proceed without a warrant. So they point the phone at your face, and all of sudden — just like your mischievous 10-year-old cousin — these officers have complete access to the contents of your iPhone X.

This is the world in which the iPhone X now exists.

There’s a solution — but it’s not necessarily a good one

It’s not unreasonable to argue that anyone worried about the iPhone X’s Face ID feature shouldn’t get an iPhone X. Other than not committing a crime, that’s the simple solution to this privacy problem.

It’s also not unreasonable to suggest that this privacy kerfuffle isn’t Apple’s fault. After all, facial recognition and other biometric security measures have existed in consumer devices long before Apple released Touch ID on the iPhone 5S and Face ID on the iPhone X. Android, for instance, has a feature called ‘Trusted Face’ that works similarly to Face ID, while Samsung introduced an iris scanner with the Galaxy Note 7 in 2016.

Both features, however, are less effective than Apple purports Face ID to be.

The issue on the table, however, isn’t who released facial scanning and fingerprint reading first, or who should and shouldn’t buy the latest iPhone.

The issue on the table is that we now live in a world where the rate of technological innovation and development supremely outpaces the rate of legislative decision-making.

The solution to this privacy challenge, therefore, isn’t to avoid buying an iPhone X. The solution to this privacy challenge isn’t to point out simple solutions, either.

Truth be told, I don’t know what the solution is. I do know, however, that the first step to solving any problem is acknowledging that there is one.

Our laws are supposed to be descriptive as well as prescriptive — they should not only look back, but they should also look ahead. As of right now, our laws are lagging far behind and the iPhone X is only the latest device to make that evident.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.