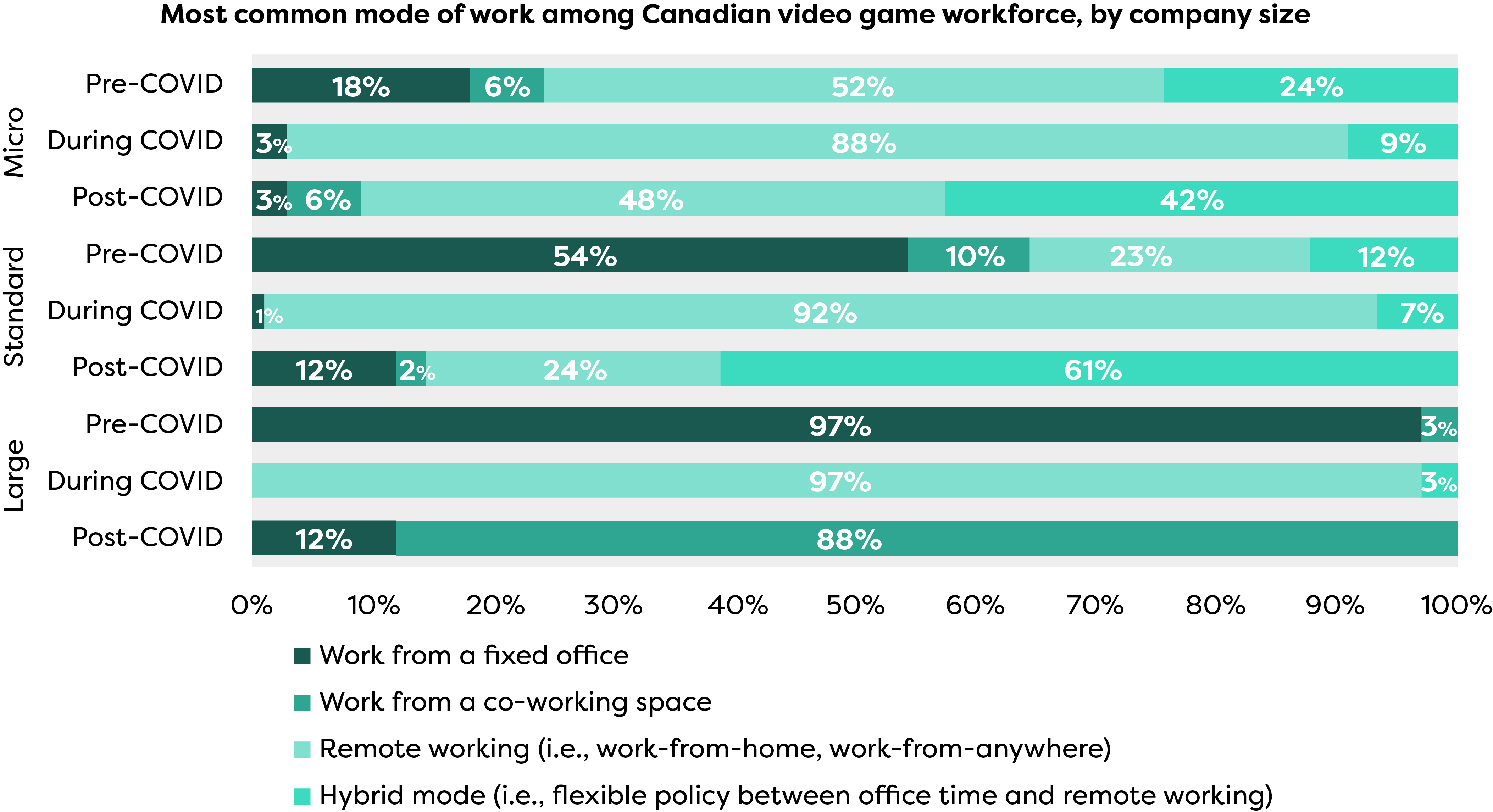

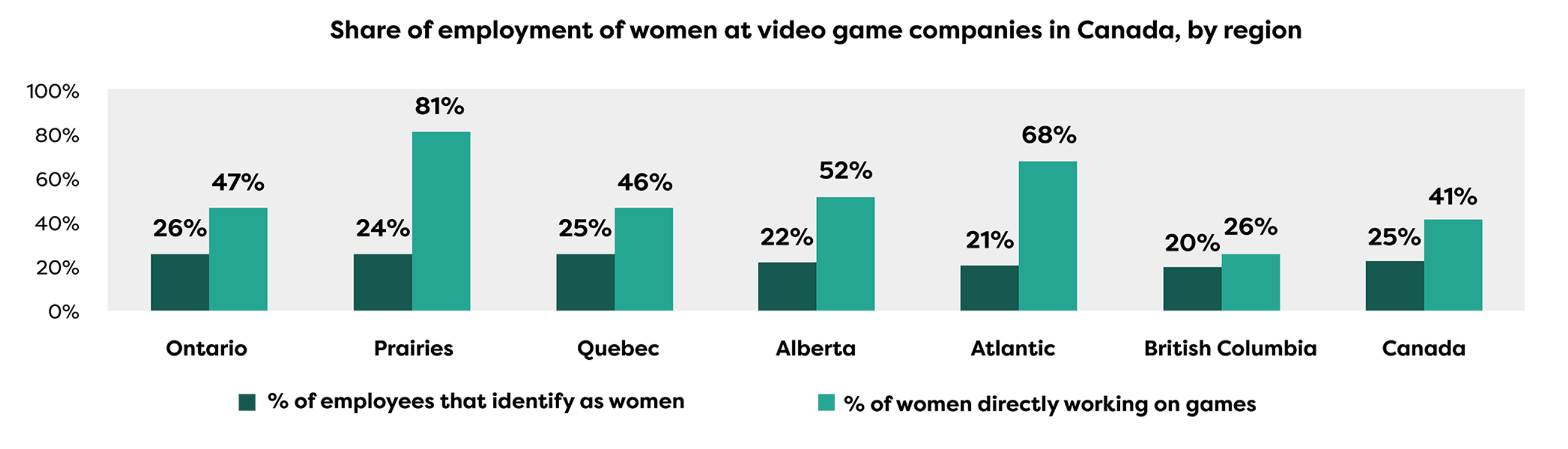

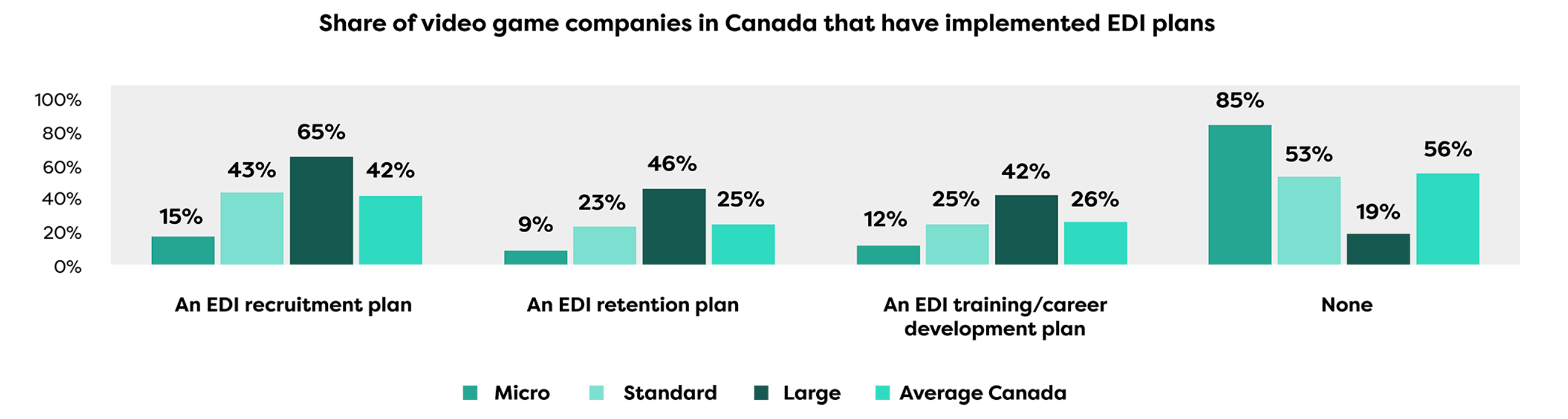

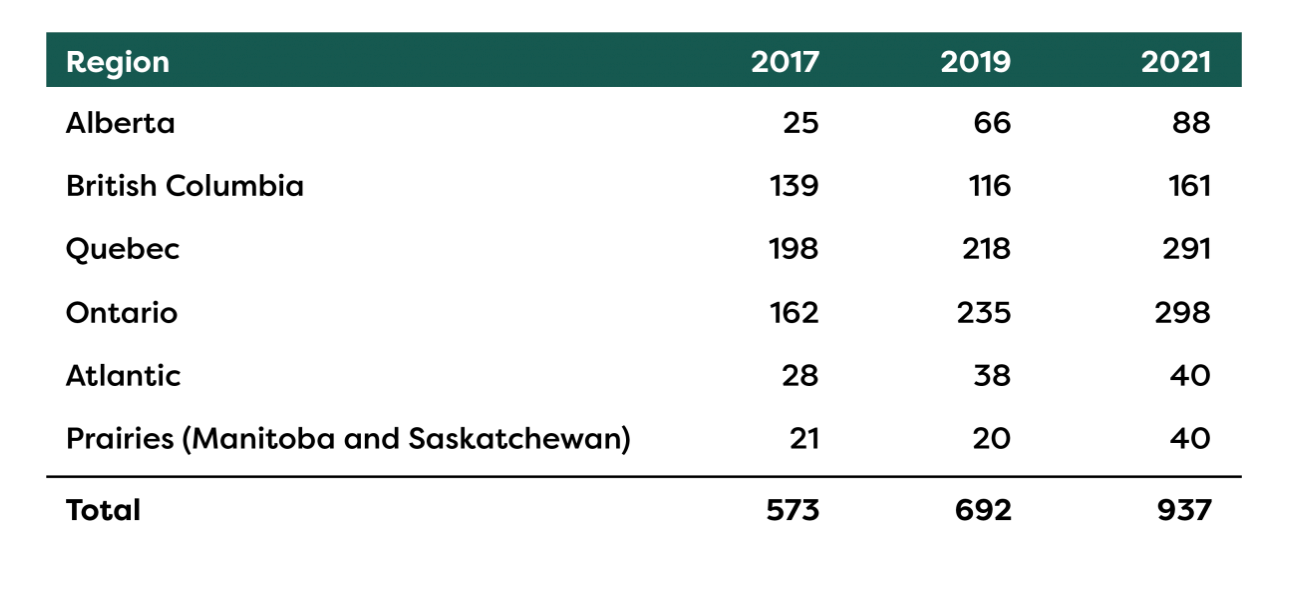

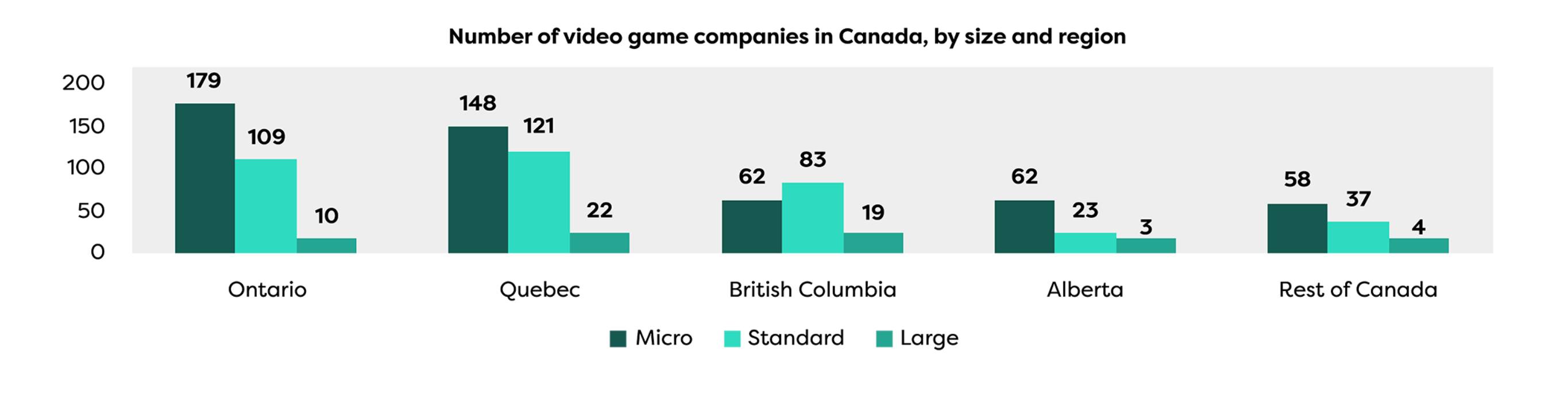

While many sectors were understandably hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic over the past year-and-a-half, the world of video games continued to grow in popularity. In Canada, in particular, nearly 60 percent of adults said they were gaming more amid the pandemic, according to a study by The Entertainment Software Association of Canada (ESAC). On top of that, 65 percent of adults and 78 percent of teens reported that gaming during quarantine made them feel better. Now, the ESAC is back with its biennial Canadian Video Game Industry report for 2021, conducted by Nordicity, which reveals a slew of data on how the national games sector has fared during the pandemic. The answer: very well. Of particular note: the Canadian gaming industry has grown 23 percent since 2019 to contribute $5.5 billion to the country’s total GDP. Further, there are now 937 active game studios in Canada, a 35 percent increase over 2019, playing host to 32,300 full-time equivalents (FTEs), up 17 percent from two years ago. “We didn’t have to invent digital channels to sell our products over the course of the last 18 months — they were already there. For years, [we’ve been] steadily improving the infrastructure and the ability to do that,” says Jayson Hilchie, president and CEO of the ESAC, of the gaming industry’s ability to flourish during the pandemic. “And so I think that what we have here is so special that we need to ensure that we continue to nurture it.” He also commended developers for being able to adapt to remote work — even when 60 percent reported less productivity amid the pandemic — so quickly. “We’re talking like 30,000 workers in Canada, and almost every single one of them being moved home, and still being able to launch the games that were in development here,” he said, pointing to the likes of Ubisoft Toronto’s Far Cry 6 and Eidos Montreal’s Guardians of the Galaxy as big Canadian titles that were still able to be completed and released despite COVID-related hurdles. “So I think it’s a testament to the industry’s technological underpinnings that allowed us to both continue to produce the products that we make, but also get them to the consumers, even in the face of physical lockdown.” Having said that, he admits that he didn’t quite expect the extent to which the gaming industry would grow amidst all of this. “I’m always surprised when I see the continued double-digit growth in jobs and GDP […] These are really big numbers, and they would be healthy in a normal time,” he says. “Being able to see that we’ve continued to hire people throughout what was an unprecedented period in our history — not just the industry, but in the world — was definitely surprising. That said, it wasn’t completely out of the realm of possibility; it just always surprises me when I see the level of growth that we’re able to achieve in this industry.” Companies are also becoming much more flexible in letting developers continue to work remotely. Per the survey, only one out of ten Large companies intend to go back to a fixed-office model, with the remainder considering a remote-office hybrid. Among Standard companies, 61 percent of respondents said they’ll attempt the hybrid pursuit, while 24 percent aim to go fully remote. Last month, a Bloomberg report noted that Quebec companies, in particular, may face some difficulty in this regard, as the lucrative tax incentives the province gives them are dependent on hiring enough people there. Hilchie says it’s important to strike a balance between bringing in more talent physically into the country and expanding where people are hired from. “I think that the most remote work situation needs to be considered very carefully. Not every job needs to have a tax credit associated for some companies, so it may be more important for them to get the person that they want and have them work somewhere that isn’t that particular province, instead of them qualifying for the tax credit,” he says. “But obviously, the more people that work outside the jurisdiction, the fewer and fewer that will be eligible for the tax incentives. And the whole point of that program is to create jobs in the provinces.” Ultimately, he says the incentives are a good way to get people “into the ecosystems” of Canada’s game development market. “I believe that it’ll be even more important moving forward with remote work that tax incentives act as kind of an anchor to keep those people here.” Hilchie also notes that it’s “really interesting” to see how different each province is when it comes to gaming. “Every ecosystem in every province has its own really unique characteristics,” he explains. “And when we talk about the Canadian video game industry, it isn’t as simple as just saying it’s one industry — it’s a number of different industries, all with their own unique characteristics associated with it. A breakdown of Canadian gaming studios by province. (Image credit: ESAC/Nordicity) For example, the ESAC singled out how, for the second time in the report’s history, British Columbia appears to be unique in that it has a greater number of ‘Standard’-sized companies — which it defines as five to 99 employees — than ‘Micro’ ones (four or less). Hilchie notes that this speaks to how old the gaming industry is in B.C., starting way back in 1982 with Burnaby-based Distinctive Software. The company would eventually be purchased by Electronic Arts in 1991 and become EA Canada (and, most recently, EA Vancouver, which makes the best-selling FIFA series). Many of these developers then went on to work at other studios, like Nintendo-owned, Vancouver-based Next Level (Luigi’s Mansion) and Vancouver-based Kabam (Marvel Contest of Champions). “And so what ends up happening is that you just have a longer time for some of these studios to develop and become Standard studios. They don’t have as many studios as Ontario and Quebec; whereas Ontario and Quebec have these massive amounts of startups and Micro studios, in combination with their Standard studios, B.C. is a much more balanced environment,” he says. “They don’t have as much new entrepreneurial activity in the Micro side of studios, but they have way more established video game companies, I would say, than anywhere else, if you’re taking into account the Standard and the Large [more than 100 employees].” Image credit: ESAC/Nordicity Overall, though, Ontario, B.C. and Quebec continue to account for 80 percent of the total number of game development studios in the country. That’s not exactly surprising, given that it’s traditionally been this way, but it’s still worth noting that there’s also been some solid growth in other provinces. The “rest of Canada” (Atlantic, Manitoba and Saskatchewan) notably added 41 studios since 2019, just slightly under B.C.’s total of 45. On that subject, Hilchie singled out Nova Scotia, which saw its Lunenberg-based HB Studios (2K PGA Tour) getting acquired by the publishing giant 2K earlier this year. 2K is also using HB as the headquarters for its broader Canadian operations. “Nova Scotia is a really, really interesting example. Because for such a small industry, there are about three or 400 people working there, and it really isn’t that old. Within the last decade, HB Studios has been around for 20 years, but the rest of the industry really kind of started the last 10 years, I would say.” He went on to mention how the Maritime province has also seen growth from Kabam, while St. John’s-based Other Ocean (Project Winter) is growing in PEI as well. “I think that’s a testament to the fact that our industry can really go anywhere.” The PGA Tour games, featuring golf legend Tiger Woods, are being made by Nova Scotia’s own HB Studios. (Image credit: 2K) That growth isn’t as widespread as he’d like, though. “The unfortunate part of the story is Alberta, where you’re seeing very little growth in an industry with some really exciting companies,” he says. “While he noted that there are some notable players there, like Edmonton’s BioWare (Mass Effect) and Improbable (led by BioWare alum Aaron Flynn) and Calgary’s Unity Technologies and New World Interactive (Insurgency), there’s overall “such little growth,” especially compared to other provinces. “That really does come down to the fact that the government has not paid the attention to the video game industry that it really needed to in Alberta. I think Alberta could be very similar to Nova Scotia on a much larger scale with big brands there if the government decided to double down on the industry. He stresses that the provincial government should pay close attention to reports like the Canadian Video Game Industry to “realize that they’re missing out” on all of that opportunity. “You’re looking at almost 5,000 jobs being created across the country in the middle of a pandemic that are paying close to $80,000, on average. If I was the premier of a province like Alberta, I’d be looking to diversify my economy, and I really think that the video game industry is a phenomenal place.” The beloved Mass Effect series is made by none other than BioWare Edmonton. (Image credit: EA) Hilchie went on to mention how skills developed for making games are also transferable to other industries, like visual effects studios working with Marvel. “You end up with other technology and IDM [integrated device manufacturer] companies that are leveraging the abilities and the innovation that the video game industry is bringing, and Alberta is missing out on so much of that.” He notes that a good start would be to reintroduce the Interactive Digital Media Tax Credit that it offered in 2019, which covered up to 30 percent of salaries and bonuses for game makers. It’s especially important for provinces of Alberta to take note, he says, because the economic impact of gaming is being seen all around the world. Hilchie specifically pointed to Ireland, Australia, Italy and Germany as four countries that have been “instituting new targeted programs” to grow their respective gaming sectors. “And so I think that what we have here is so special that we need to ensure that we continue to nurture it. Making sure that those government supports and targeted incentives are available for the industry and remain, making sure that immigration streams are there for us to find the right targeted talent around the world, [and] ensuring that we start looking internally to build the natural resources pipeline of digital skills that’s going to go forward.” When speaking to MobileSyrup in 2019 over that year’s industry survey, he noted how he also wanted to see improvement in the representation of women. Per the 2021 study, women now account for 23 percent of the Canadian developer workforce, up four percent from 2019. While Hilchie says he’s glad to see that number rising, it’s still nowhere near where he’d like to see it. It should be noted that the survey was conducted between May and July, meaning it couldn’t take into account the industry’s response — or, in some cases, lack thereof — to widespread allegations at Activision Blizzard of a “frat boy” culture that regularly mistreated women. Similar reports have come out at Ubisoft, including at its Toronto and Montreal studios, which have reportedly not yet been addressed by the company. “…people still look at the video game industry as really this kind of enigma.” Per the survey, 56 percent of Canadian video game companies have not developed an equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) plan. However, 81 percent of ‘Large’ companies reported having adopted at least one type of EDI program. Hilchie says the number is lower among smaller teams because they’re spread relatively thin by focusing on actually making games. Overall, though, he says he believes EDI is a “priority for most companies.” The problem, he argues, is that there are actually many jobs that are going unfilled. “We are facing a massive labour crunch in our industry — we’re growing so fast that we can’t find the people, in a lot of cases, to fill the jobs,” he says. “Right now, there are roughly 2,000 unfilled jobs in Quebec — there would have been close to 3,000 new jobs created in Quebec in the last two years if they were able to fill all the different jobs that they have available. But the problem is that there’s such global competition and national competition for this skill set that it’s becoming harder and harder.” What will ultimately make this easier, he says, is “a total focus on diversity and inclusion and getting more women” into the video game industry. “When I’ve talked to the deans of computer science programs at universities, they tell me that their enrollment is only 15 to 20 percent women. How do we ever get beyond 15 to 20 percent women in our industry if they’re only graduating 15 to 20 percent women from [computer science] programs?” he questions. “So the problem exists before they even enter in the technology industry. And so we need to work with the government to reform the education system to be able to expose young girls and people from all backgrounds to computational learning and technology at a much younger age — I’m talking [kindergarten] to [Grade] 6.” He notes that much of what the federal government has done has been with third-party organizations like the non-profit Kids Code Jeunesse, who go into schools to promote STEM education. “But that’s like a day here, a day there — we need computer science to essentially be the same as chemistry, biology and physics,” he says, noting how such coding-related classes just aren’t as prevalent.

“If you knew you wanted to get into physics in university, you could have three years of physics in high school before you ever get to university, but you can’t do that with computer science. Oftentimes, people end up in computer science programs at universities, it’s the first real formal CS class they’ve ever taken […] So we have to make digital technology and learning accessible and attractive to people from all backgrounds in order to six the diversity and inclusion issue.” He thinks this could go a long way towards promoting the video game industry to larger groups of people and, in turn, bring more into it. “The video game industry is definitely a credible economic sector, there’s no question about that, but people still look at the video game industry as really this kind of enigma,” he says. “But in order for us to be mainstream, I think people need to see their friend’s sister or their own sister working in the video game industry. And I think that that’s really where we need to go.” This interview has been edited for language and clarity. Header image credit: Square EnixStrong growth, even during a pandemic

Breaking it down from province to province

The importance of diversity and inclusion

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.