Welcome to Tête-à-Tête, a series where two of our writers converse on interesting topics in the mobile landscape — through chat. Think of it as a podcast for readers.

This week, Douglas and Daniel ponder whether the rise of mid-range phablets in the 5.3″ to 6.3″ range are killing tablet sales, or whether people are tired of carrying around too many devices.

Douglas Soltys: Daniel, the world is coming to an end, at least if you are a tablet maker. According to the IDC, the worldwide tablet market grew just 11% this quarter. Best Buy’s CEO says tablet sales are crashing, and even Apple’s tablet shipments are down 9% year-over-year for the quarter. Dogs and cats are living together; it’s mass hysteria!

Or maybe not: while IDC projects strong growth tablet growth in Europe, Asia, and the rest of the world over the next three years, it also projects that North America will flatline. So I ask you, sir, what’s killing tablet sales so close to home?

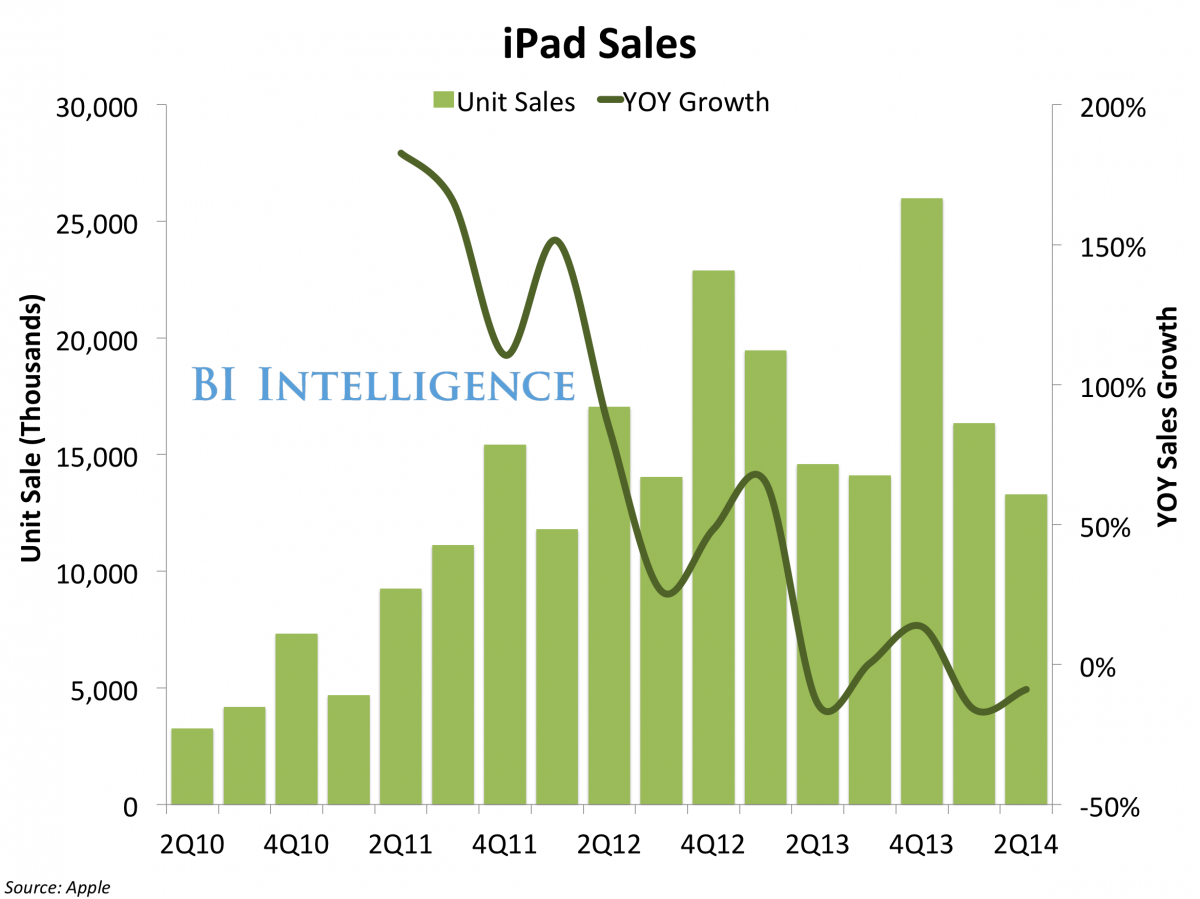

Daniel Bader: There are a number of factors slowing the tablet sales market, but things are not as dire as you intimate. North America picked up on tablets more quickly than the rest of the world, so the slowdown is happening here first, beginning with the iPad. Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, acknowledged that the tablet market was born of pent-up demand that lifted the industry from zero to 100 in just under two years. More specifically, between Q4 2010 and Q4 2013, traditionally, the company’s biggest sales quarter, the iPad went from 7.5 million to over 25 million units. But unlike phones, tablets have a longer replacement cycle, as they are not used for as many mission-critical functions.

Moreover, between the middle of 2010 and the end of 2013, the average phone size increased from 3.5-inches to 5-inches. As a result, the things that we could previously only do on tablets are becoming more easily accomplished on larger-screened smartphones, also known as phablets. When the Galaxy Note was unveiled in 2011, its 5.3-inch display was considered enormous, and Samsung marketed it as a high-end product with unparalleled performance. Today, we wrote about a 5.3-inch phablet from Sony that will likely cost under $300 outright.

The commoditization of large smartphones is having a direct impact on tablet sales, especially in the Android arena, and while the overall market is growing, it appears that consumers are choosing to buy larger, mid-range smartphones and hold on to their laptops for more comprehensive productive spurts.

Douglas Soltys: Your case for pent-up demand and longer replacement cycles makes sense, but leaves many unanswered questions. First among them is why someone would prefer a phablet to a tablet? I get that as the tech has gotten better, screen sizes have expanded in search of an equilibrium, but things are starting to get literally out of hand. The Samsung Galaxy Mega is 6.3 inches! Can that even fit in a pocket?

Could it perhaps be that everyone in the 21st century requires a smartphone, but they don’t necessarily require a smartphone plus a secondary device (i.e., a tablet), and thus choose the biggest smartphone they can afford? Put another way, people will choose an unwieldy 6 inch phablet over a 7 inch tablet and a smaller, yet functional, smartphone.

If that’s the case, what implications does this push towards bigger have on the nascent wearables market? Will consumers be more likely to purchase a smartwatch if they have a smartphone that’s too large to be readily available?

Daniel Bader: I think there’s a point to be made about the confluence of smartwatches and phablets; the former doing triage for the latter makes more sense when the latter is too cumbersome to remove from one’s pocket or bag. These days, smartwatches are to smartphones as smartphones were once to laptops, a slightly more manageable conduit to managing content.

It also stands to reason that wearables, as they stand right now, are more aimed to fill the gaps in platforms that tablets never could quite get right. The prospect of using a tablet to create or consume content seems great for most people, but once they saw it was possible to consolidate that experience into a single device — a larger phablet — many took the bait. That the larger phablets quickly lowered in cost, many of them becoming free on contract, made, or is making, the prospect of spending that extra cash on a smartwatch more attractive.

Indeed, as the smartphone did with the home phone, the camera, the MP3 player and, increasingly, the laptop, larger smartphones are mitigating the need for a tablet in many homes.

But the North American market is just one place: inexpensive tablets still have huge potential in emerging markets, especially since smartphone penetration has not reached the same heights as it has here. For tablets, that’s where the growth is. But do you think Canadians have checked out of tablets completely, or are we just in an awkward teenage phase right now?

Douglas Soltys: I wouldn’t exactly call it an awkward teenage phase, but it’s certainly a period of self-discovery. Tablets definitely have huge potential in emerging markets, where, like smartphones, they can function as laptop replacements — although in that case, radio-enabled tablets are a must, as reliable Wi-Fi access simply isn’t prevalent.

In North America, I think we’ve finally reached the point where the newness of the tech has worn off, and we’re starting to realize that we simply don’t need a device in every form factor: wearable, smartphone, tablet, laptop. I believe this is less about cost and more about redundancy: even you and I would be hard pressed to rock all four device types day-to-day — and we work in tech.

If that’s the case, the tablet market — like the wearable market, the smartphone market, and the laptop market — will continue to ebb and flow as technology advances, forcing consumers to regularly reconsider the two (maybe three) devices they’re willing to take with them each day. We’re at the point now as well where no one combination is vastly superior to the alternatives, but there’s enough value amongst each to win over small pockets of advocates.

In other words, expect a lot of college-era experimentation.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.