When Meagan Byrne co-founded her Hamilton, Ontario-based indie game studio with Tara Miller in 2016, they named it “Achimostawinan Games” after the Cree word for “tell us a story.”

As an Âpihtawikosisân (Métis, Ontario) artist, Byrne wanted there to be an Indigenous-led developer that would make games focused on Indigenous stories. Now, six years later, Achimostawinan has been recognized for that work by some prestigious figures in the gaming industry.

Earlier this month, Achimostawinan took home the top honour in the Ubisoft Indie Series, an annual competition to award two Ontario indie studios with funding and mentorship from Ubisoft and National Bank. As the Grand Prize Winner, Achimostawinan receives $50,000 in funding, while the Special Prize Winner, System Panic, is awarded $25,000.

Congratulations once again to Ubisoft Indie Series Grand Prize winner @AchimoGames and @nationalbank Special Prize Winner SYSTEM PANIC! 🎉 Missed the awards ceremony? Catch the highlights: https://t.co/RQh2IV3eGO

— Ubisoft Toronto (@UbisoftToronto) May 7, 2022

“That was amazing. At first, I didn’t actually believe we won,” Byrne tells MobileSyrup. “When [Ubisoft Toronto juror and developer Andy Schmoll] started doing the vagaries of the studios, I was like ‘that could be anybody.’ And then I was like ‘wait a minute.’ And then they said our name, and it took me a second. ‘Did I hear that right?'”

Achimostawinan is being recognized for Hill Agency: Purity & Decay, a “cybernoir” detective mystery game about an Indigenous P.I., Myeengun Hill, who’s hired by a woman to investigate her sister’s murder. The project first came together in 2017 at a game jam hosted by Dames Making Games, a Toronto-based non-profit aimed at supporting women in game development. Byrne now serves as the main writer and game designer on Hill Agency.

Right away, the game sticks out for having a striking Blade Runner-esque futuristic setting: a North American city in the year 2762. Byrne says the decision to give Hill Agency such a backdrop initially came about from a deep love of sci-fi.

“I’m very into Terry Gilliam and Brazil came to mind when we were thinking about places — how it’s so very grounded in his childhood and the world of the adults that he saw in his childhood, but he’s just transposed it into the future and kind of added a few features that way,” explains Byrne. “We did that to start because I love that kind of weird sci-fi, where you’re like, ‘this is barely sci-fi.’ And that’s how we started and it just really connected with people.”

But this far-future period also gave the team the opportunity to develop a narrative centred around one key question: “What would our world look like on the brink of freedom from colonial oppression?” It’s a story that has gained even more relevance over the past couple of years as many more Canadians have learned about the country’s residential school graves and other horrific crimes against Indigenous peoples.

While Byrne says these acts haven’t changed anything with Hill Agency‘s core story — “we already knew about this stuff, we just didn’t have public proof of it” — they have influenced her overall approach to the subject matter.

“I think what it has made me want to do is be ever more careful about how we talk about things. I think when I first started the game, it was a little bit brasher — a little bit more ‘in your face.’ As I sort of worked through the story and polished and cut, I started realizing some of these things could be too triggering to some of my audience,” says Byrne. “But I don’t want to not talk about these things. So how do you play that line? And I was like, ‘I will do what we always do — I’m going to throw in some cheese and laughter and kind of create these spaces where you’re not so invested and it doesn’t feel so real, because you’ve got that terrible Harrison Ford narration over top. You can’t take it too seriously.”

While Byrne makes that Blade Runner reference with a laugh, she’s also quick to mention that she wants to give the game a “sort of heightened reality rather than reality, because so many Indigenous people have to deal with this reality every day.”

Of course, that’s not to say Myeengun’s story won’t still be grounded in Indigenous experiences. For Byrne, Hill Agency is a way to “talk about a lot of things that come up in the community that we don’t really talk about publicly” — namely, family.

“Part of the whole thing with [Myeengun] is that she literally lives in a neighborhood that is completely made up of her family. She doesn’t live with strangers — essentially, everyone there is related to her somehow, either through marriage or through adoption, or [by] blood. And we don’t just tell the player that right away — you figure it out fairly quickly, because of how everybody talks to you. But you get this casual kind of, ‘oh, is this what it’s like?’ This is what it’s like when things are good and healthy.”

She says players will be able to revisit this area as the narrative eventually takes darker turns for a sense of comfort. “I kind of wanted to make a safe space for the player in the game.” Cree characters and language have also been strewn throughout Hill Agency to create a more unique and authentic experience.

Another notable aspect of Hill Agency is that it doesn’t have any combat. Instead, players make choices throughout their investigation, and these will affect the story as a result — no “game overs” are present. Initially, this focus on a combat-free gameplay system came down to budget considerations and doubling down on the strengths of their small team.

But Byrne adds that she was conscious of the fact that some games have forcibly included combat to the detriment of their stronger elements. “One of the things I’ve seen over and over again is, ‘oh, the art was great, the story was good, but I hate the combat or these mechanics.'”

She says she brought this up to the team early in development and specifically cited Murdered: Soul Suspect, the Square Enix-published 2014 adventure-mystery game from the now-defunct developer Airtight Games. “I love the investigative part of that — I think it’s a fantastic investigative game. And they shoehorned a whole bunch of combat and sort of avoiding [enemies], and I hated that,” says Byrne.

“For us, it was, ‘What tools do we have to do this? Well, writing.'”

Getting to tell your own stories

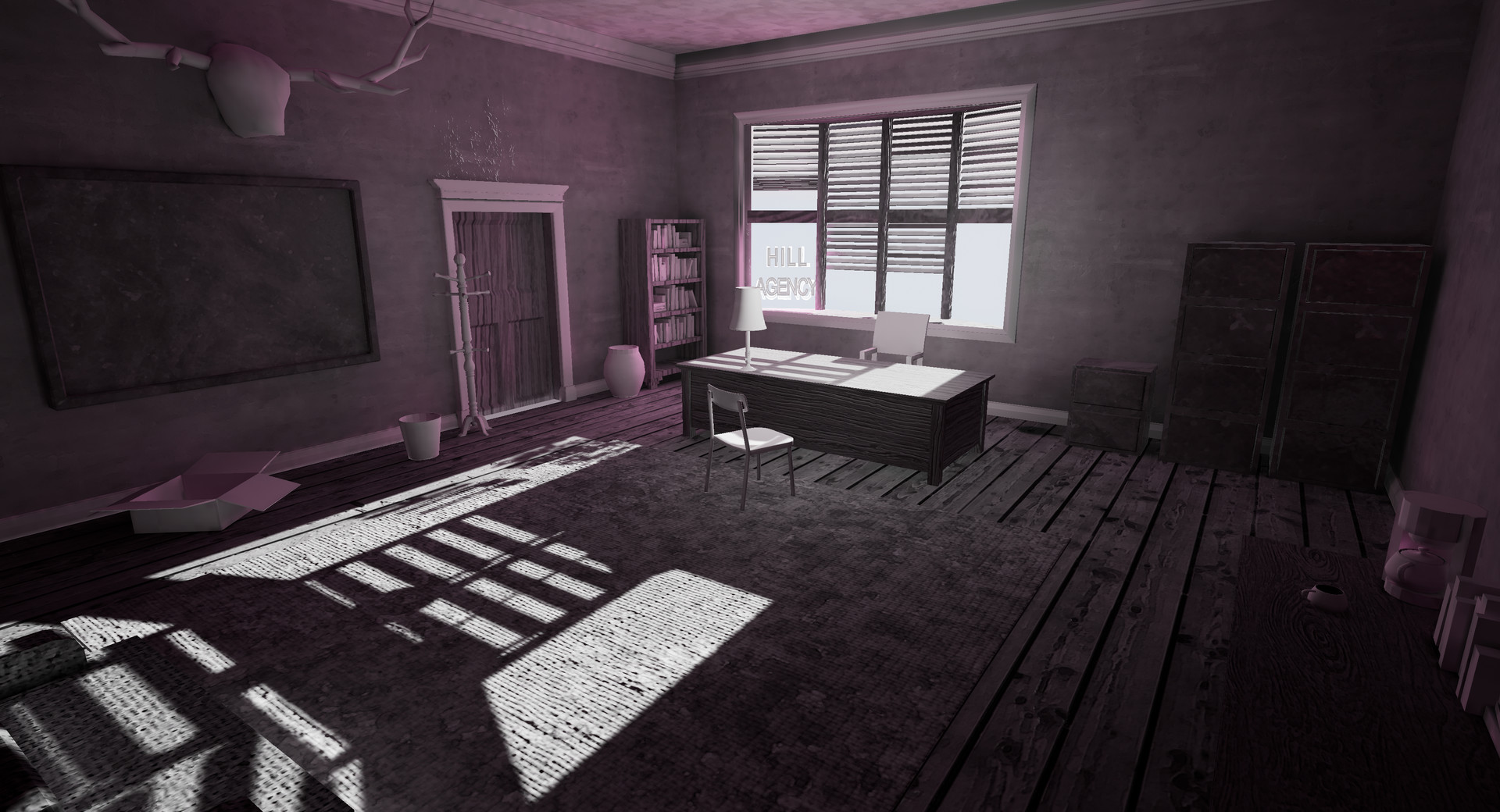

Hill Agency office (Image credit: Achimostawinan Games)

Before Achimostawinan, Byrne was working in theatre — that is, until the financial crisis in the mid-aughts led to mass layoffs and show closures. “My career just kind of got sliced in half and stopped,” she explains.

Knowing she had to try something else, Byrne enrolled in a game design program at Sheridan College and quickly found a lot in common with theatre.

“When I started, they were talking about how everyone wants to do cinematics, they want to do film. I was like, ‘this is literally theatre, and your player is one of the actors. This is awesome, I know how to do this!’ So I was right away getting into it,” she says. “And all I had to do was just reframe who the audience was because the audience is no longer passive — they’re not just receiving, they’re participating. So you have to write a role for them.”

In this case, she knew she wanted to write roles for Indigenous characters. The problem, however, is that she was never really given the opportunity.

“Up until that point, I’d never been kind of encouraged to talk about my culture — to talk about my feelings of belonging. Being Métis in Canada is a politically, internally and externally fraught existence. Marriage laws and such have had long-term detrimental effects on a lot of Indigenous people today who don’t have access to that community. In my own way, I don’t have access to my traditional community,” she says. “And I didn’t know how to talk about that, and I wasn’t encouraged to talk about it at school. Why would you? You’re here to learn games.”

She credits Indigenous performing artist and teacher Archer Pechawis with inspiring her to focus on what she wanted to talk about in a game.

“That was like a lightbulb moment for me. We could talk about difficult, awful things without literally talking about it, or without making it super plain to everybody that this is a sad or hard or painful thing.” This inspired her to “play around” with a platformer prototype that doubled as a metaphor for the “difficulty of navigating these spaces,” which helped lay the groundwork for her future game dev work.

“I was very, very thankful that they helped me get started in the space. And then I wanted to give back — I wanted to return and re-invest the investment they put in me,” she says. In her case, this has meant working closely with groups like Dames Making Games, Indigenous Roots and imagineNATIVE and hosting events like Night of the Indigenous Devs 2020.

“We can’t just keep putting them into things, and not exploring or examining. Why did I think that’s a shorthand for ‘exotic?'”

“That was important to me because I just didn’t see places for Indigenous people making weird digital stuff or video games to showcase their work the way they want it to be showcased. We’re still being kind of pigeonholed into this, like, ‘new media’ — it’s very Canada Council, very gallery, which didn’t vibe with a lot of us. And then imagineNATIVE is very film and television. And you don’t just watch a game, you play a game. So again, that didn’t really vibe. And it was difficult to kind of know that this isn’t how you want your work being shown, but also not being able to communicate how you want it being shown.”

Getting to experience all of this for herself made her feel “so special” and “so wanted,” she says. “That’s why I do it — to get other people to be like, ‘I’m gonna make more games now.'”

The importance of Indigenous representation

Kotallo, left, is one many tribal warriors in Horizon Forbidden West (Image credit: PlayStation)

Of course, there are non-Indigenous developers who also games featuring such subject matter, which clearly runs counter to what Byrne is talking about. This was most recently exemplified in PlayStation’s Horizon Forbidden West, an action-adventure game featuring various warrior tribes during a post-apocalypse. Some Indigenous gamers and creators have criticized Forbidden West — which was made by Guerrilla Games, a predominantly white team in Amsterdam — for creating stereotypical Indigenous imagery and characters.

For Byrne, it all boils down to whether Indigenous content needs to be in a game to begin with. “If it doesn’t change anything with the story, just take it out, because it means you’re just using it for flavor. And that’s what I see a lot. It’s not about even representing anyone; it’s just ‘I’m looking for a visual shorthand to get across something.'”

The problem with this, Byrne says, is that people don’t even think about where said shorthands come from. “We can’t just keep putting them into things, and not exploring or examining. Why did I think that’s a shorthand for ‘exotic?’ Why did I think that was shorthand for ‘primitive?’ Why did I think that was shorthand for ‘stupid?’ These are long-standing tropes that we have internalized because our parents and our grandparents internalized them.”

She acknowledges that “we’re all kind of guilty of taking in things from other cultures and then regurgitating them in such a way that we think tells this different story than what it’s really telling,” so it’s important to be “reflective” and “respectful” or what you’re actually doing. For stories that do need to involve an Indigenous character, Byrne urges teams to actively involve those from that given community to ensure authenticity.

But on the whole, she says developers like Guerrilla should just “find a studio that’s Indigenous” and let it tell that story instead.

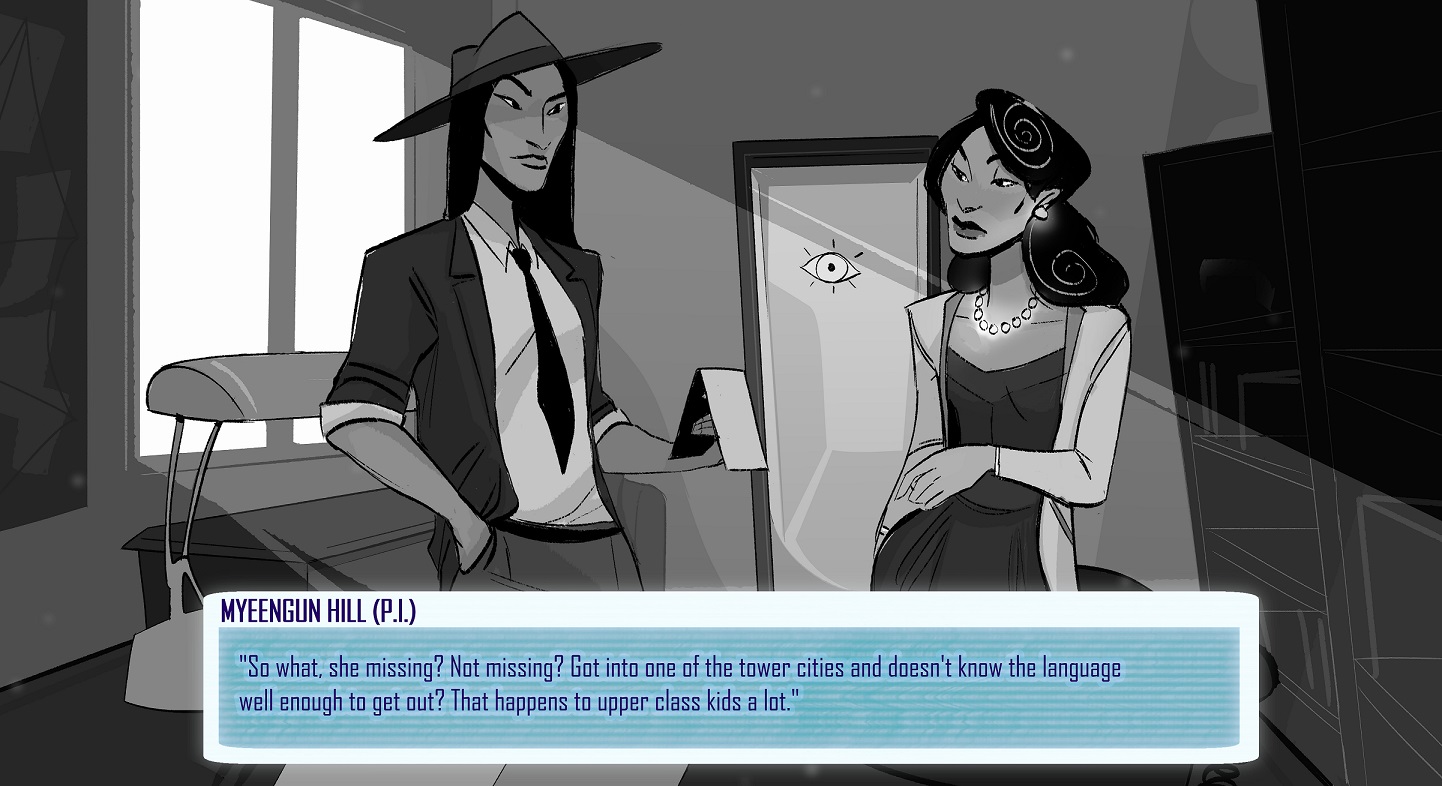

Myeengun in Hill Agency (Image credit: Achimostawinan Games)

“What I don’t love so much hearing about is, ‘oh, this studio was going to write a game about this Indigenous nation. We don’t have anybody on the team who’s from this nation. We don’t even have anybody on the team who’s Native.’ Why? Why are you telling this story?” she says.

“Sometimes there’s an inclination — and this [happened] a lot when the Truth and Reconciliation came out, and they started having to teach about residential schools in Canada — for a lot of younger people and older people [to be] like, ‘I just learned about this, I need to tell this to everybody — I need to tell this story!’ Why do you have to tell this story? Why not look for others who are involved directly and are already telling the story? Amplify them — spend the money on them. That would be really lovely if we could kind of disengage from this ‘I’ve got to be the guy’ attitude that I see in games a lot when it comes to Indigenous people and let them tell their own stories.”

In so doing, these people are “going to tell a story that’s not going to be grounded in the sort of way we see ourselves,” she says. “You’re always going to be looking from the outside. And so you’re going to be seeing these sort of trappings of culture, rather than the nuances behind that — an ‘under the road’ kind of idea. Because the way we see ourselves, at first glance, probably doesn’t look very different from [how] anybody looks at themselves in their culture.”

On that note, Byrne points out that there are several Indigenous creators in Australia and New Zealand that have been releasing such games, including the former’s Origame Digital (Umurangi Generation). “That was fantastic. Nowhere in it did he really advertise, ‘Oh, this is an Indigenous game.’ But if you play it almost immediately, if you’re a Māori person, you would be like, ‘oh, I recognize those symbols.’ And it’s a very lovely surprise. And then for everyone else, it’s a really cool photography game.”

Umurangi Generation is a Māori photography game from Australia’s Origame Digital (Image credit: Origame Digital/Playism)

To that point, Byrne says games like Umurangi Generation can be a great way to simultaneously celebrate Indigenous peoples while also introducing those from other cultures to it.

“Sometimes, I hear people describe a similar feeling when they’re playing these games to like when I first started watching anime. I really liked it, but there were things that would happen that were obviously a cultural note that I was like, ‘what does that mean? I don’t understand — this is definitely not made for me.’ But I still enjoyed it, and the stories will resonate,” she says.

“People are free to engage with Indigenous stories that are made by Indigenous people. ‘I’m not going to get it’ — do you watch anime? Do you read manga? These are not ‘made for you,’ but you like them nonetheless. Why? Because stories connect. Just because you don’t get the underpinnings all the time, doesn’t mean you’re not going to connect with it.”

Looking back, and looking ahead

Reflecting on everything, Byrne says winning the Ubisoft Indie Series has been validation for all of her work and the broader significance it carries.

“You have to understand — we hadn’t really shown too much of [Hill Agency] to very many people. It had just been our Kickstarter, and we’re not talking directly with the Kickstarter backers. So to hear somebody who’s never seen it before, go, ‘Oh, my God.’ And these are industry vets that I respect […] It really made me feel like we were on the right track.”

That was especially important to hear, she says, because of the challenges of an upstart team making a game during the pandemic. “Everything has been very stressful there, and this has been a very rough go. We’re kind of an untested team. It took a really long time for us to get full funding for the project. And then when we did, it was like, COVID [happened], there were certain systems I didn’t know I needed to have in place, there were certain roles I wish that I had not taken on that I had found somebody else to take those on… There were lots of things I didn’t know.”

She’s also started to think about game development as “this is me learning,” which has helped significantly.

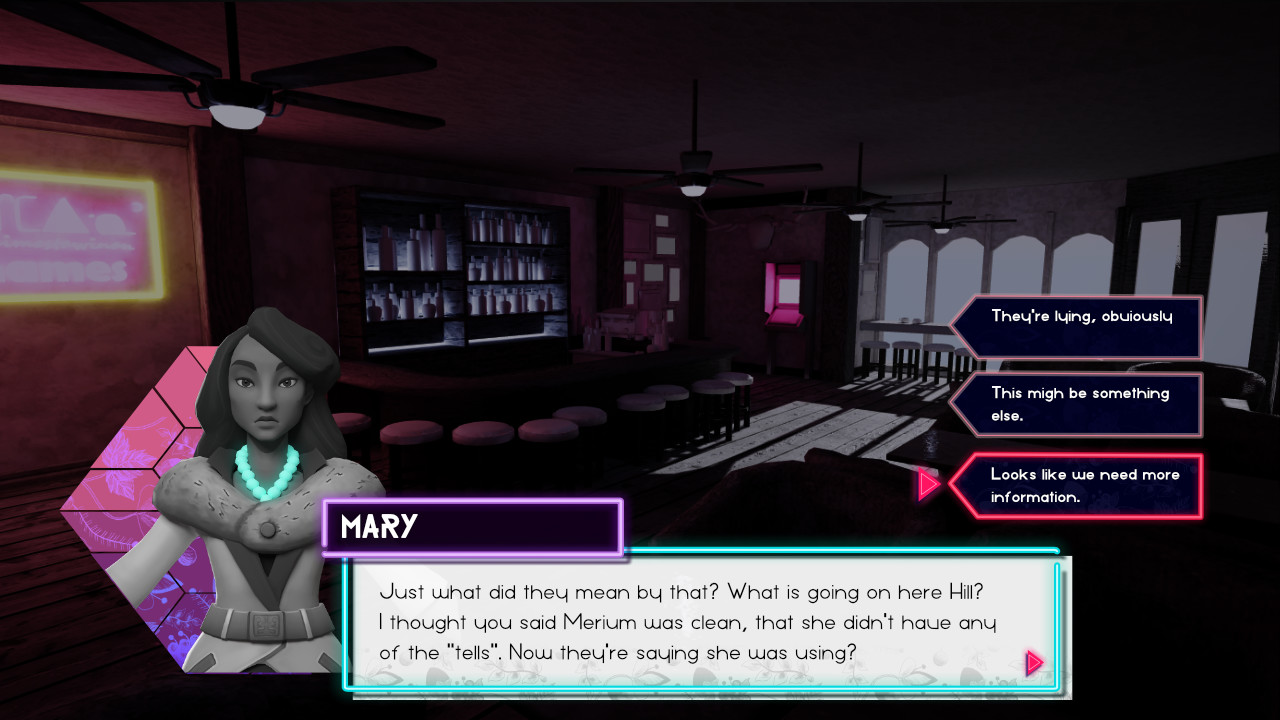

Dialogue choices in Hill Agency (Image credit: Achimostawinan)

“I’m being taught through my actions and my work — learning a lot about what are all the processes that need to happen to make a project start, to keep a project going and to finish it. Because honestly, a lot of times the finishing never happens, and that is definitely the hardest part. So getting the funding was just a little bit of a load off of things that we’ve been really worried that we were gonna have to just stop early because the money would be gone. And it’s more important to get it done.”

As Achimostawinan works towards doing just that with Hill Agency, Byrne also has some advice for other aspiring Indigenous game devs.

“Start small. There are lots of different small groups that are trying to teach code, that are trying to teach game development tools. One of the things that a lot of Indigenous people struggle with, especially if they’re up north, is internet — it’s just not accessible. So what I would also like to see is more things like libraries and even big software companies kind of offering a USB key you can take with you or come to the library and you can work on it. I have seen it more in cities, but there are rural and reservation spaces that need this as well.”

At the same time, she says to not let a lack of resources hold you down.

“Just make. A lot of times people are like, ‘oh, I have to have this, I have to have that.’ Like, you can just have a pen and paper. There are lots of free books out there. But also find your community. Sometimes that can be the hardest thing — just finding the community that’s also making game. My big belief is that the Indigenous people that I see most successful in making games have found a group that could support them when things get rough. And I think if you’re aspiring, find that group, treat them well, make sure they treat you well, and you’ll probably find yourself taking off a lot faster. Because a lot of the load will be taken off. That’s what I love about Indigenous game devs — I always feel like somebody’s like, ‘Oh, let me help. Let me do what I can.’ It’s really necessary and it’s really helpful, especially when you’re trying to figure out where to go.”

Hill Agency: Purity & Decay is set to release on August 31st on PC. You can wishlist the game on Steam.

Achimostawinan Games is based on Hamilton, Ontario, which is recognized as being part of the Between the Lakes Treaty or Treaty No. 3.

Correction: Hill Agency is currently only confirmed to be coming to PC. This story previously mentioned Mac and Nintendo Switch as well. It has been updated accordingly.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.