It was a big day for Rocket Adrift.

On February 9th, the three-person Toronto-based indie studio was awarded the Grand Prize at Ubisoft Indie Series, securing $50,000 in funding and mentorship opportunities from Ubisoft and National Bank. The team’s past two games, a smaller Itch.IO project called Order A Pizza and the larger, more widely sold Raptor Boyfriend, were both visual novels.

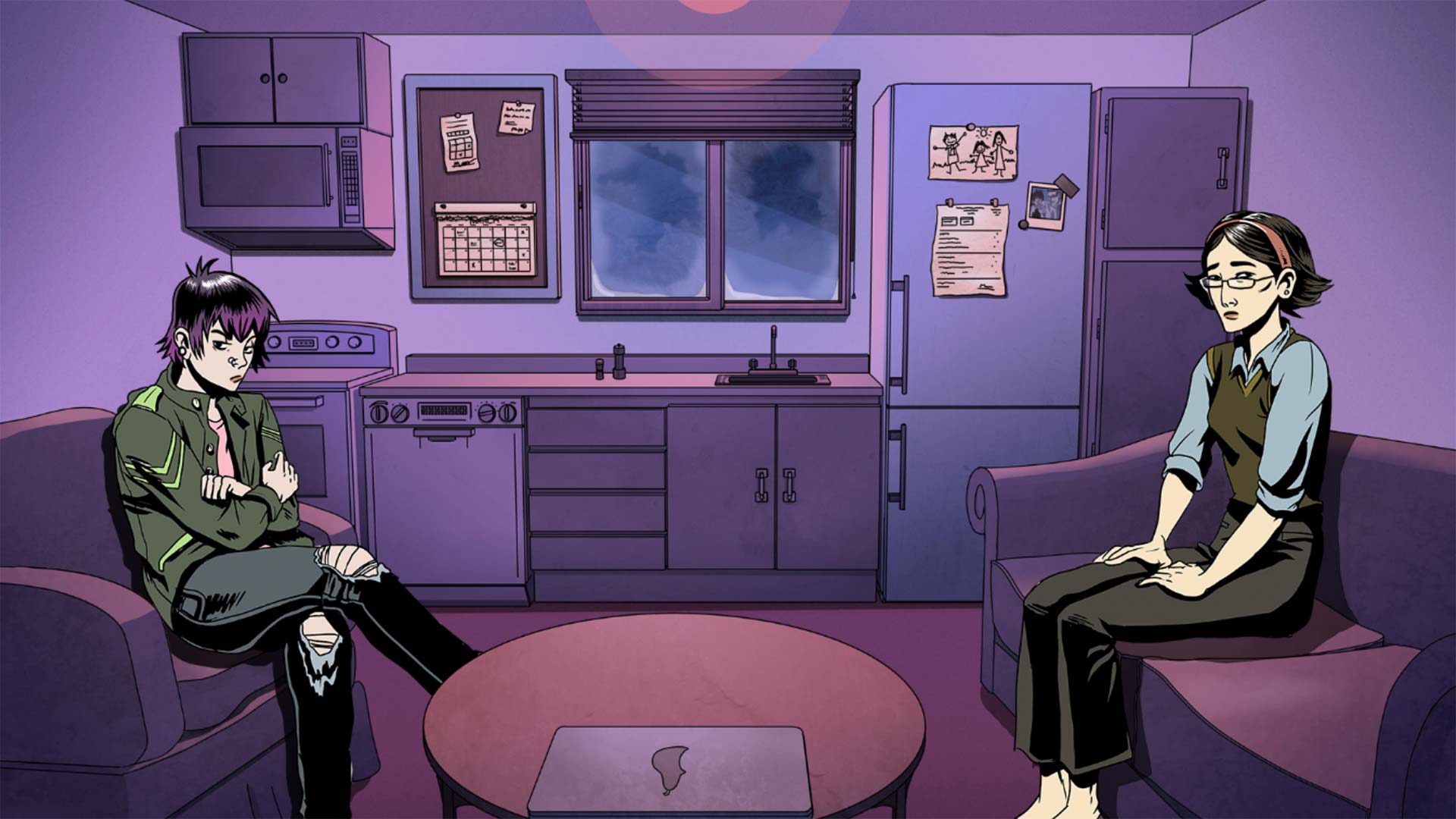

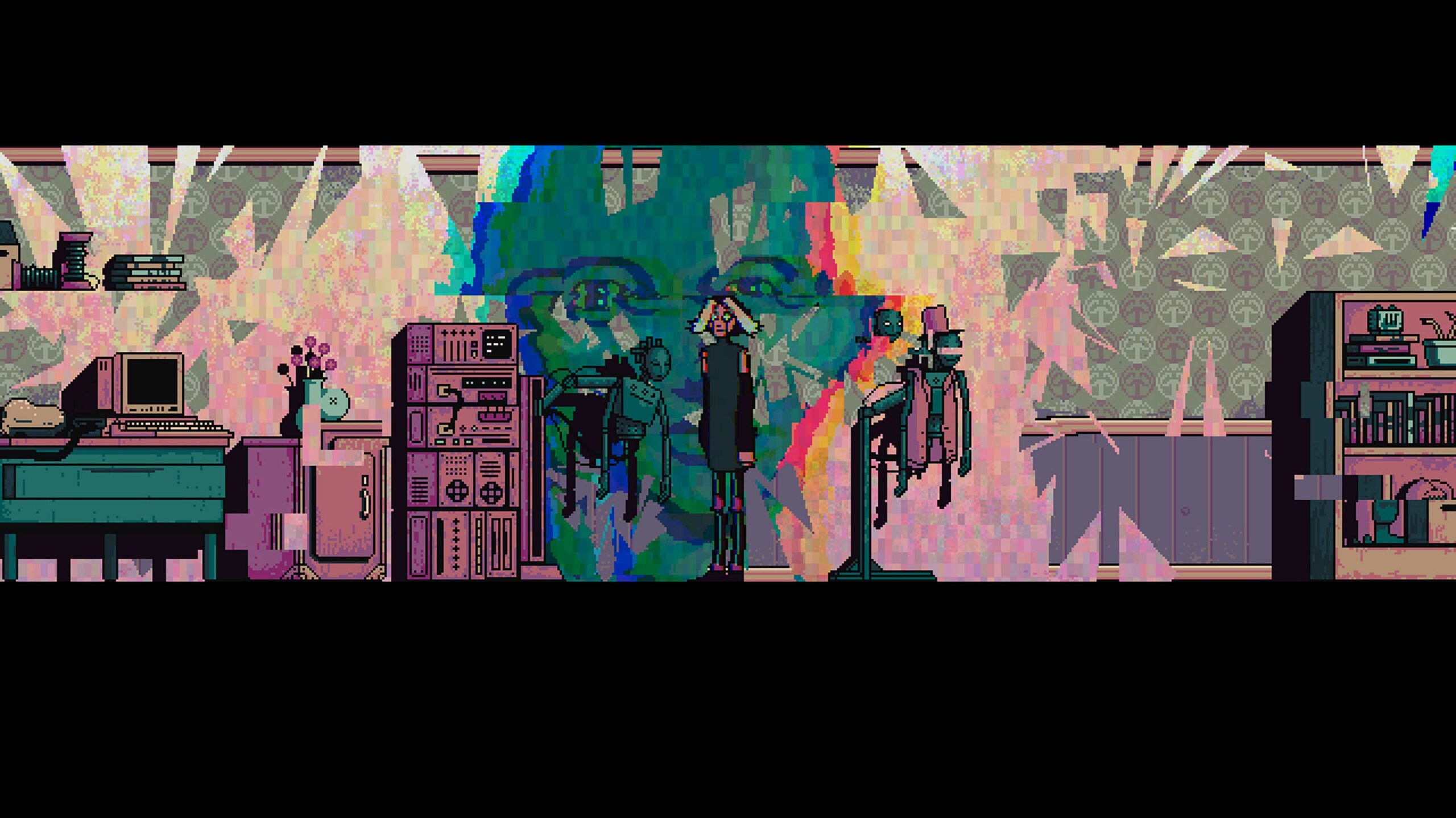

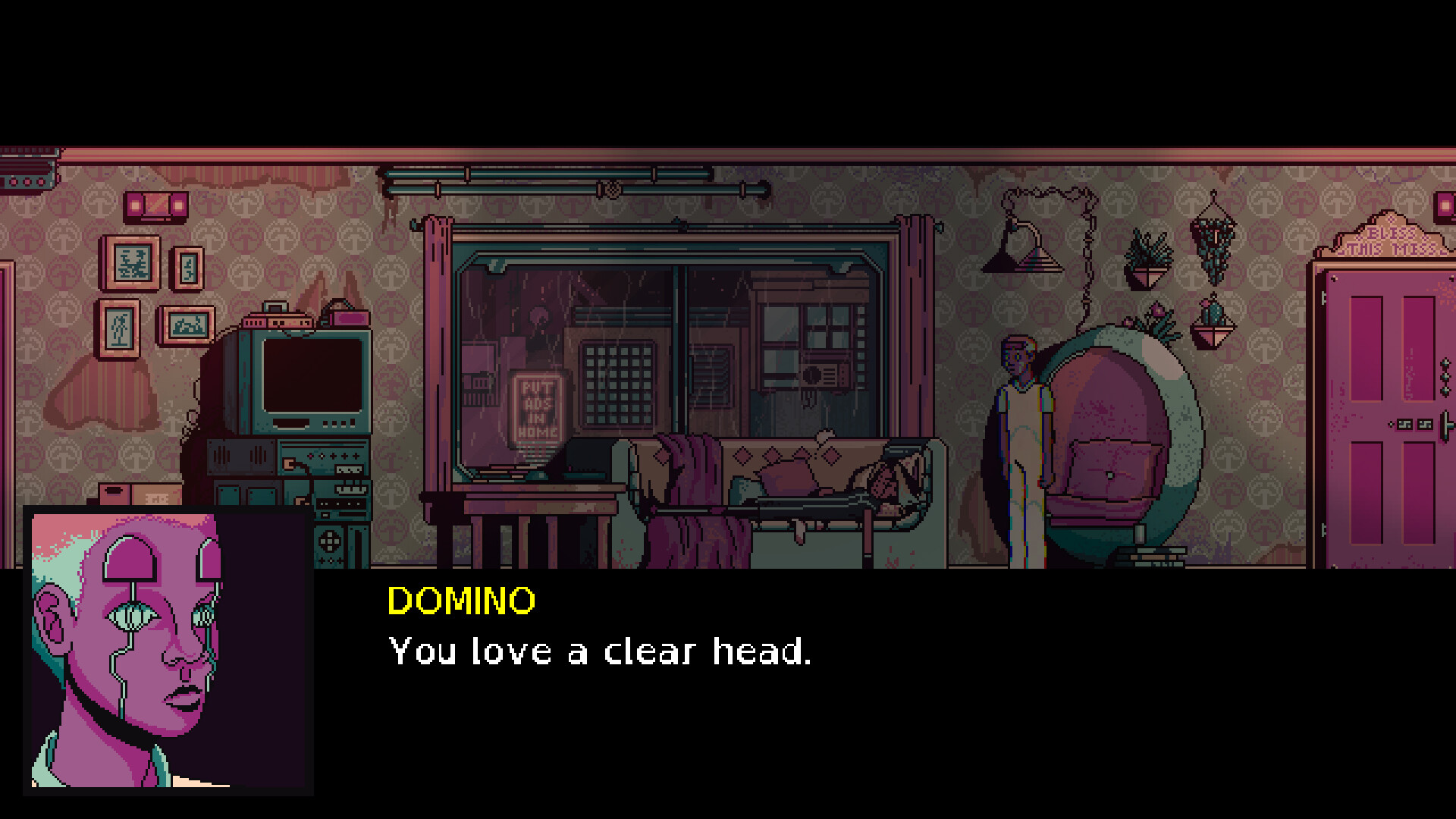

Now, Psychroma, the team’s first crack at a narrative cyberpunk sidescroller, is already getting major recognition within the industry. The game follows a non-binary digital medium, Haze, as they piece together broken memories in a cybernetic house.

Naturally, this whole experience has been overwhelming for Rocket Adrift.

“We had set ourselves up to accept the disappointment of not winning. We just didn’t expect that we would have won,” says co-founder, writer, programmer and character artist Lindsay Rollins.

“It hasn’t sunk in yet, still — it’s been weeks,” adds Sloane Smith, co-founder, writer, composer and background artist.

“I always try to get ready for the worst possible outcome and everything. I don’t really allow myself to enjoy it until it’s confirmed,” remarks Titus McNally, co-founder, writer, lead programmer and UI/UX designer, with a laugh. “That’s my strategy — I don’t know how healthy it is.”

They’ve come a long way since meeting at Toronto’s Seneca College in the Independent Illustration program. After working in animation for a few years, the trio made the pivotal decision in 2017 to break into the gaming industry through Rocket Adrift.

“It’s a medium where you can not have voice acting, and there’s a lot more flexibility in the world of video games,” says Smith of the decision to shift to game development. “But that gave us the opportunity to tell a longer story, versus doing two-minute animated shorts. We were stuck in that realm of animation because it’s too hard to produce anything else.”

Of course, making such a change is easier said than done. “We kind of came into it with the hyped-up ego of somebody who’s new at something thinking that they’re gonna change the industry and make some great game,” admits Smith with a laugh. “And then we were humbled quickly by how difficult it is to make games.”

What helps, however, is having a small, close-knit team that jives well together.

“We all just kind of switch hats when it comes to the development and design parts of the game,” explains Rollins. “We have our specializations […] but we all write, all design, and we all code to a degree.”

Tackling a new type of game

One quick look at Psychroma reveals a decidedly darker experience than the colourful Order A Pizza and Raptor Boyfriend. As Smith puts it, they’re both “kind of silly on their face.” While players have praised Rocket Adrift’s previous work for their emotional depth and 2SLGBTQIA+-friendly themes, Rocket Adrift does feel that the goofier elements sometimes misrepresented their intentions.

“It was really hard to sell people that we’re going to make something that says something interesting,” admits Smith. “We wanted to make it more obvious upfront that we like to tell stories that have an impact and say something and can go deep. We decided that a psychological horror game with a narrative-heavy direction was going to be easier to get people to understand what we were trying to do. As well, we wanted a bit of a departure — more interactivity in the gameplay, and to just kind of push ourselves a little bit to try something new.”

“We were kind of burnt out from like the teen coming-of-age, romantic dating sim comedy kind of genre, and in our true fashion, we pivoted completely opposite to less humorous and more horrifying,” adds Rollins with a laugh.

The darker tone also lets them expand on their love of the cyberpunk genre, which they currently explore in a recreational role-playing podcast called Dark Future Dice.

“[We wanted] a narrative that was representative of the disillusionment of marginalized identities within that kind of dystopian future,” says Rollins. “A lot of popular cyberpunk media really focuses on what we would describe as a ‘dad rock’ mentality of cyberpunk where it’s basically a male power fantasy. It’s not so much talking about the socio-economic issues that the cyberpunk genre has really pioneered.”

A key part of that, says Smith, is the “psychological” aspect of cyberpunk. “A pretty famous theme in cyberpunk is what makes humans human, and we wanted to focus on that and talk about identity. How much does your identity matter in who you are? And how much do memories play a part in that? So we want to just focus more on the cerebral side of it and less on the action side, technological side.”

One way they’re tackling said psychological elements is through non-linear storytelling. As Haze, players will encounter fragmented memories that distort space and time, giving the game more of a trippy feel. It’s that sense of unease over what might happen next that goes hand-in-hand with the type of cyberpunk tale they’re targeting.

“By making it in the horror genre, we’ve tried to really depart from that power fantasy,” says McNally. “It’s sort of the opposite thing where this stuff has control over you, rather than you having control over it.” He says he wants this narrative to have more of a profundity to it in the way that the best psychological horrors tend to grab you. “Your mind is constantly turning over the bits and pieces of it and it hits you in a way where there’s this unanswered question that lies with you while you’re in bed at night thinking about that media, and I hope to capture that in the game.”

This approach presented its own challenge, however, as the team needed to maintain a “pretty loose” narrative structure compared to the far more scripted and tightly laid out visual novels.

“In Raptor Boyfriend, [the narrative planning] was a slowly growing or merging kind of Google document that was continually expanding. And for this game, it’s a series of boards and murals that really look like that meme from Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” says McNally with a laugh.

“It’s super different, and there’s definitely a challenge to it. But I think with this style of game, you have to be okay with a little bit more ambiguity in the story,” notes Smith. “I actually think that’s a point for this type of storytelling, especially when it’s horror and psychological.”

Adds Rollins: “I’m realizing, too, that we’re probably going to be working on the narrative structure to the end!”

Bringing it closer to home

On its website, Rocket Adrift says its mission is to “tell personal narratives that highlight the perspectives of LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC experiences while also showcasing an outsider lens to Canadian culture.”

Smith says that the “outsider lens” comes naturally to the team. “Our writing and our wits and our outlook on things is kind of uniquely Canadian. None of us feels like we super fit in when the Toronto culture specifically and stuff like that, but we still are obviously influenced by it. So it kind of helps to bring a unique angle toward stories.”

Raptor Boyfriend certainly leaned into the silliness.

While all of this subject matter factored into Raptor Boyfriend, the team says it was heightened. As Rollins notes, Raptor Boyfriend was meant to “give a sense” of what it was like to grow up in ’90s small-town Ontario, albeit in more of a “fantasy” version of that setting. “We wanted a nice, comfortable story where a marginalized identity person could enjoy that coming-of-age story without having to deal with the realities of that.”

Psychroma, then, is a chance to lean towards realistically portraying Canada. “For Psychroma, we need to think more about how Canadian culture might reflect the dystopia of the world. But I think one of the things that definitely we want to tackle is the rent problem, the housing crisis — that should play a big role in the narrative,” says Rollins. “And that’s something that Torontonians — and just a lot of other people in major cities — would be able to relate to.”

As McNally tells it, Psychroma presents the “worst-case scenario of what could happen if we don’t start thinking about neighbourhoods and communities” in Toronto.

“It takes place in this old house surrounded by these modern buildings, mega city structures, and it’s a safe haven for marginalized people to find some kind of housing,” says Smith. “Without going too much into the story, it struggles to stay up because of the outside world and past mistakes by other generations.”

But even if you’re not a Torontonian, Rocket Adrift hopes the larger explorations of representation and identity will resonate. As mentioned, Haze is a non-binary protagonist, and she’s also mixed-race. Some of the supporting characters, meanwhile, include Salem, a trans woman; her disabled lesbian partner, Agatha; and people with different kinds of neurodiversity. For characters whose lived experiences don’t directly relate to any of the Rocket Adrift team members, consultants have been brought on. But on the whole, the story and characters draw heavily from their creators’ own lives.

“I think stories about mixed race or non-binary people are very few and far between. And usually, when they’re included, they’re either not the main characters, or their identity doesn’t really play into the narrative in any meaningful way,” says Rollins. “When I go to play games, I want to see myself represented in them in that way. Why not be the example you want to see in the world?”

For Smith, a trans woman, stories like this can even be life-changing.

“Games are an incredible vehicle for people having some empathy for people that may not be like them, or may not look like them, but they are still figuring things out. For example, when I played a little indie game, Secret Little Haven, about a trans girl who was figuring herself out, it was like a lightbulb moment for me that I just didn’t see coming,” she says.

“It’s just something about being in the shoes of that character that can make you understand things a little bit better. Games are a really powerful tool in that way, too — just have some self-discovery while you play. Representation is more than just seeing yourself sometimes; it’s also about helping people understand.”

“I hope that [players] are able to cultivate empathy for people that might be in dire situations such as this,” adds Rollins. “But I’m also hoping to just scare the shit out of them and make them cry. I’m always looking to make people cry!”

This interview has been edited for language and clarity.

Psychroma is set to release in Q4 2023 on PC (Steam).

Image credit: Rocket Adrift

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.