Over the past few weeks, I’ve kept coming back to this recent Q with Tom Power interview with Matt Johnson, the director of last year’s incredible BlackBerry.

During the chat, the Toronto-based filmmaker talks about his desire to elevate Canadian creators around the world due to a general lack of awareness. As he tells it, “ninety-nine percent” of the international people he’s talked to during the making and promotion of the film didn’t even know that BlackBerry, the iconic phone brand, was made in Canada.

“It’s almost like this didn’t happen on the world stage. Our country doesn’t get the credit for the fact that we invented the smartphone,” he said, making a salient, albeit disheartening, point.

While Johnson goes on to discuss his efforts to address the lack of acknowledgment of Canadian films, that sentiment is certainly just as valid in other fields. In particular, it got me thinking about my own primary passion, video games, and how often the Canadian gaming industry tends to be under-appreciated.

Despite being a $5.5 billion powerhouse in a country with a relatively small population, it rarely gets its due recognition.

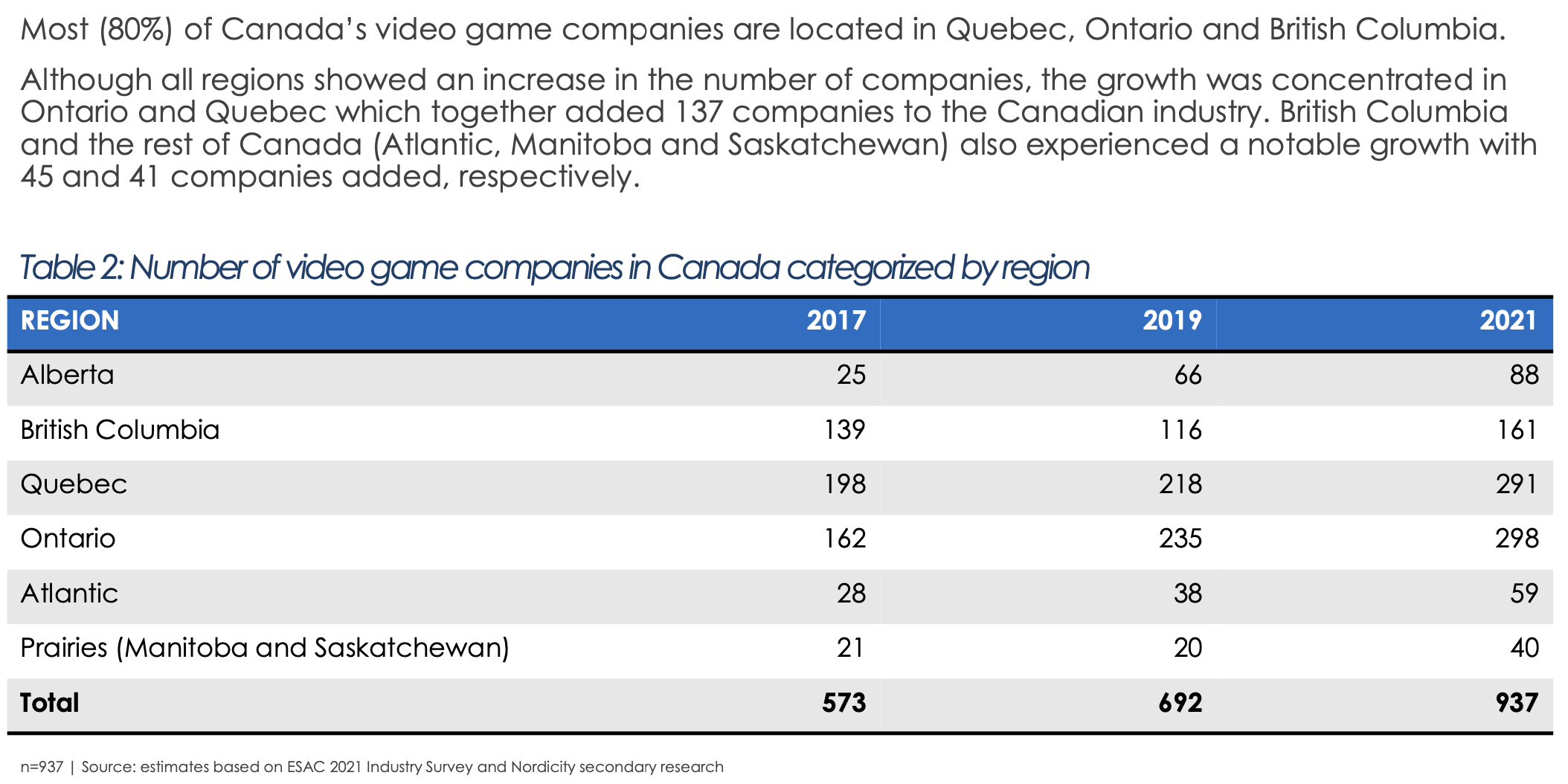

A provincial breakdown of the number of gaming studios in Canada as of 2021. Image credit: Entertainment Software Association of Canada

To put this into context, it’s safe to say that most people would likely know (or at least assume) that games like Mario, Zelda and Final Fantasy were made in Japan, or Call of Duty, Fortnite and Counter-Strike hail from America. After all, those are the two biggest countries in the world for game development. But when we move onto the third-largest hub of game makers, Canada, the conversation seems to shift towards a resounding “Huh?” That’s certainly not due to a lack of Canadian games.

FIFA (now EA Sports FC) is always among any given year’s top-sellers, but how many people actually know it was made by EA Vancouver?

Lots of people recognize Ubisoft as a French company, but do they know that most of their biggest titles, like Assassin’s Creed, Splinter Cell, Far Cry and Rainbow Six: Siege, were primarily made at Ubisoft Montreal?

Warframe is one of the rare multiplayer games to maintain popularity for 10 years, but you likely wouldn’t have realized it’s made by Digital Extremes in London, Ontario.

There’s a lot of demand to this day for a remaster or remake of 2003’s The Simpsons: Hit & Run, yet most probably wouldn’t have guessed it was made by a Vancouver team, Radical Entertainment.

People undoubtedly know BioWare for its work on beloved and iconic RPG series like Baldur’s Gate, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, Mass Effect and Dragon Age, but how many are actually aware that the EA-owned studio is located in Edmonton?

And that’s just on the AAA side. Some of the most celebrated indies — which already get less attention, to begin with — have been made in Canada, like Cuphead (Oakville, Ontario’s Studio MDHR), Celeste (Vancouver’s Extremely OK Games), Inscryption (Vancouver’s Daniel Mullins), To The Moon (Toronto’s Freebird), Spiritfarer (Montreal’s Thunder Lotus) and last year’s viral hit Venba (Toronto’s Visai Games).

And yet, we don’t see any of this reflected in the public eye. In that CBC interview, Johnson said he wagers that random people on the street would likely not be able to name a single Canadian film, and I’d imagine that extends to gaming. All the time, I have people respond to the pieces I write, like this one about 2024 Canadian games, with “I didn’t know [insert game/developer] was Canadian!” Hell, just this week, I had my trainer at the gym — who is otherwise pretty savvy about games — say he didn’t even know Ubisoft had a Toronto team, even though it’s been around for nearly 15 years and has released such prominent games as Splinter Cell: Blacklist, Watch Dogs: Legion and Far Cry 6.

That said, I can hardly blame them. The gaming industry does little to promote Canadian creators, so why would everyday people know of them?

There are a multitude of reasons for this, I imagine. First, the video game industry is frustratingly secretive in a way that other artistic media, like film and television, just aren’t. Indeed, it’s rare for studios — which operate behind tightly shut doors — to give us the kind of intimate look that Ubisoft Toronto did for Far Cry 6. (Even something like the Ubisoft co-produced Mythic Quest on Apple TV+ can offer some insight, however small, to casual audiences, especially through its recurring gag about the game producers back in Montreal, although there’s really nothing else like it.)

Further, Canada itself is home to so few events, despite us having an ever-growing roster of nearly 1,000 game development studios. The U.S. has big shows like PAX (and, for many years, E3), Europe has Gamescom, Japan has Tokyo Game Show and even the likes of England and Mexico got their own Xbox events right before the pandemic. Canada, however, has no sizeable consumer events, only industry-facing ones like the Montreal International Games Summit (MIGS) and the XP Game Developer Summit. (We had the PAX-like EGLX, which quietly went away, while Fan Expo no longer provides the big game demos it once did.)

It’s a shame since these kinds of events are a perfect way to promote local game creators, like how Ubisoft Toronto once hosted demos and meet and greets for Watch Dogs: Legion at EGLX. Activision has also put on neat Fan Expo panels with the likes of Quebec City’s Beenox and Sledgehammer Toronto so they can discuss working on Call of Duty in Canada. But otherwise, there’s little else. In fact, one of the few programming efforts here, the Canadian Game Awards, faced a litany of issues last year. (Disclaimer: I was a juror on the 2023 CGAs.)

Meanwhile, Canada is certainly not getting much love on the global stage, either. Geoff Keighley, the Canadian creator of The Game Awards and Summer Game Fest, will occasionally pay lip service to developers from his native country, but that’s always second fiddle to celebrities and ads. Moreover, the show’s jury — which consists of more than 100 international outlets — exhibits a paltry representation of Canada that includes Screen Rant (a site owned by Montreal-based Valnet but primarily staffed by Americans) and has featured The Gamer (another Valnet publication that otherwise predominantly employs Brits.) This isn’t to throw shade at these sites (far from it, as I enjoy their work!) but rather to highlight how Canada is bafflingly overlooked even in situations where we absolutely shouldn’t be. Why aren’t we representing ourselves on the global stage?

Mainstream news representation is important, but there are lots of great gaming and tech-focused publications that should be on that list, especially given the impact games developed in Canada have on the global industry. pic.twitter.com/MUwK9WLPWH

— Patrick O'Rourke (@Patrick_ORourke) November 27, 2023

All of this is important for several reasons. Besides just giving our incredibly talented creators more of a much-deserved spotlight, it also helps show the next generation of aspiring game makers that Canada is indeed a place of opportunity. While there’s nothing wrong with leaving the country for other ventures, people should at least know about the many options they have here, and yet, they likely don’t.

As an example of this, Quebec City-based Sabotage’s Thierry Boulanger, the creative director of last year’s award-winning Sea of Stars, recently talked about how he once thought that video game development wasn’t a viable career option for him in Quebec. Speaking on the AIAS Game Maker’s Notebook, he explained how there’d been a perception that games had to be made in English and he’d have to leave Quebec if he wanted to pursue game development. “For a very long time, it was kind of like an abstract idea — ‘It would be nice, but unfortunately, it’s not for me because of circumstances,” he said.

It was only after seeing Ubisoft Montreal’s Prince of Persia: Sands of Time — one of the most beloved games of all time — in 2003 that he realized the potential within his home province. “‘Okay, this was made here and it’s ‘internationally relevant.’ I’m starting to understand now that locally and around me, there can be an industry — it can exist,” he said of his response to the game. Now, it’s better understood, at least among developers, that Quebec is one of the world’s biggest hubs for game development thanks to lucrative tax incentives and a massive talent pool.

Clearly, then, there’s real power in being able to see people from similar walks of life achieve success. It’s inspirational! And even if you’re not looking for an actual career in a given field, there’s still something undeniably cool — that sort of fellowship and pride — that comes from seeing other countrymen and locales being recognized. I’d wager that’s a big reason why our coverage of HBO’s The Last of Us resonated so much last year. By highlighting the show’s Alberta production, we reached hundreds of thousands of people who were excited to see their province get big shoutouts from the likes of Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey. We rarely see that sort of thing otherwise.

Ultimately, I don’t know what the long-term solution should be when it comes to getting more acknowledgment for Canadian games and their creators. Realistically, I don’t expect some seismic shift to happen overnight or even in the next year or two. But at the very least, it would be lovely to see just a little more representation and recognition of Canadians and their many contributions to the gaming industry.

Host more events here and let fans put faces to the developers who work so hard — yet deal with so much — to make the games we love.

Organize more showcases, especially those that promote indies, and emphasize games that are Canadian. (Some, like Annapurna Interactive’s, commendably do highlight the country of origin.) We make enough games — maybe we can even get our own Canadian-themed digital Wholesome Direct-style presentations?

Involve Canadians more on the global stage, be it at The Game Awards or other events. (Seriously — Americans and Brits shouldn’t be representing us!)

Canadians are responsible for some of the biggest and most beloved games in the history of the medium. Let’s show them some love, eh?

Image credit: EA

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.