New rules governing the use of drones by recreational users prohibits flying near buildings, people, animals, and airports; imposes a $3,000 fine if you’re caught.

Drones, quadcopters, or UAVs as they’re officially known, have been a hot consumer item for several years, and are becoming more and more popular. Research firm Tactica last year estimated that the market for these airborne cameras would balloon from 6.4 million units in 2015 to 67.9 million by 2021. And though drone prices are gradually coming down, the NPD Group says that at least 56 percent of buyers are dropping $500 US or more on a new drone purchase, a price that indicates these are not just toys for annoying the family pet.

But Canadian drone buyers might soon be flying back to their retailer for a refund. New Transport Canada rules governing the use of recreational drones were announced by Minister Marc Garneau on March 16th, surprising both drone owners and manufacturers, even though there had been hints that stiffer regulations were coming.

The new rules, which went into effect immediately, stipulate that as a recreational drone pilot you may not fly your drone:

- higher than 90 m above the ground

- closer than 75 m from buildings, vehicles, vessels, animals, people/crowds, etc.

- closer than nine km from the centre of an aerodrome (any airport, heliport, seaplane base or anywhere that aircraft take-off and land)

- within controlled or restricted airspace

- within nine km of a forest fire

- where it could interfere with police or first responders

Further, there’s no flying at all at night or in clouds, you must keep the drone in sight at all times, and you must be at most 500 m from your drone. Finally, your name, address, and telephone number must be clearly marked on your drone. The fine for breaking any of these conditions is up to $3,000.

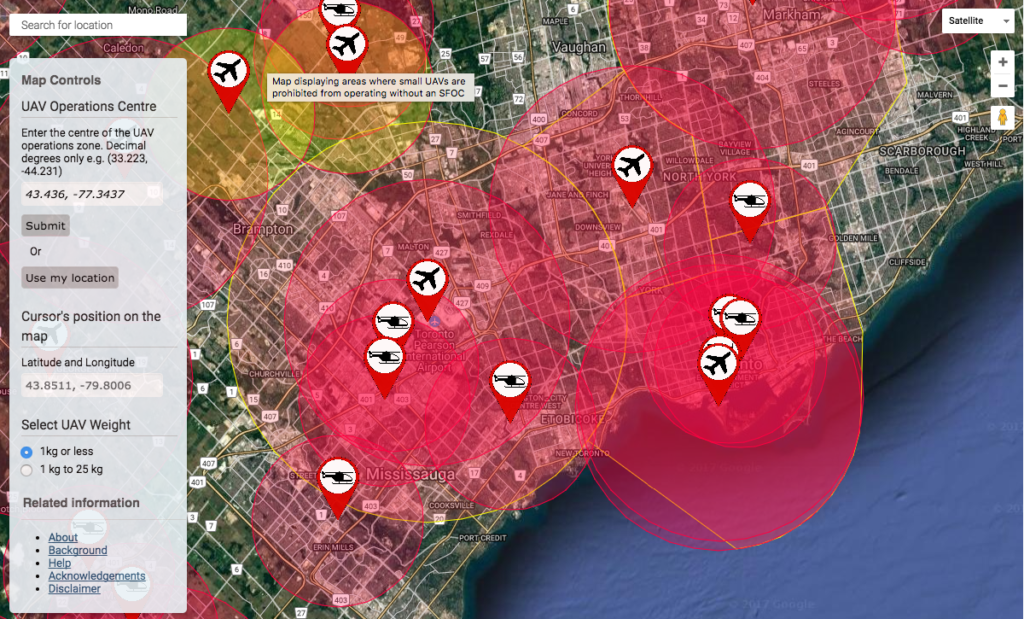

Some of the rules, like the ones covering forest fires or first responders, seem obvious and will likely affect very few recreational pilots. But others, such as the nine km minimum distance from an airport, have effectively created massive no-fly zones across the country, especially in urban areas. The National Research Council (NRC) maintains a site that drone pilots can use to determine they’re operating within an illegal distance from an airport. Most of southern Ontario is covered by dozens of overlapping red circles, leaving only a few small rural areas where recreational flight is allowed. The same is true for every major Canadian city.

Garneau characterized his announcement as being all about improving safety. “When it comes to safety, I don’t think anything is overkill,” Garneau said in response to a reporter’s question, according to the CBC. “I have read almost on a daily basis reports from pilots coming into airports, on the flight path, and reporting seeing a drone off the wing.”

According to Transport Canada, which responded to MobileSyrup’s inquiries via email, there were 148 “reported drone incidents” last year, a increase of 300 percent from 2014, when there were only 41. The government agency did not define what it meant by the term “incident.” It also characterized the response to the new rules as positive, claiming that, “stakeholders were very supportive of the initiative and did not foresee any negative impacts on their members.” But questions remain about just how many recreational drone pilots belong to the stakeholder groups, which include the Model Aeronautics Association of Canada (MAAC). In fact, MAAC received an exemption from the new rules for its members flying at MAAC sanctioned fields and/or events.

Transport Canada says that its actions are a response to municipalities, aviation associations, law enforcement and the general public, all of whom have contacted it over the last few years with “strong concerns surrounding the increased operation of recreational drones.”

Among those who were not consulted, reaction to the new rules has been mixed, with strong opposition being expressed by the Drone Manufacturers Alliance (DMA). It criticized the government’s actions, saying the the new measures will not significantly improve safety. “Aviation authorities around the world have never recorded a single confirmed collision between a civilian drone and a traditional aircraft,” the Alliance’s executive director, Kara Calvert, wrote in a press release. The rules apply to all drones that weigh between 250 grams and 35 kilograms, which covers all of the drones made by the Chinese drone giant, DJI, including its highly portable (and hugely popular) 734 gram Mavic Pro model.

Professional UAV operators are cautiously optimistic about the new rules. “We’re looking at it as a positive thing,” Tom Comet, owner and operator of DroneBoy, a Canadian aerial cinematography company based outside of Toronto, told MobileSyrup.com. “But it’s going to make people not want to get into drones,” he said, “which is kind of sad. Most people who end up being professional drone operators start out as recreational pilots.”

Drone enthusiasts are decidedly unhappy with the rules, with many saying they’re too restrictive. Reddit user _hugerobots_ said, “So if you don’t have a vehicle to drive out far enough to be 9km away from any where air or water craft area, you’re left with… national parks? Where you’re also not allowed to fly…,” a sentiment echoed by other commenters in the New Canadian Drone Laws thread. “I was looking into buying a phantom this summer and getting into the hobby but there’s no point now,” user killjoy269 added.

Steve Barnes, a member of the private Facebook group, Toronto Phantom Pilots, questions the logic behind the altitude restrictions. “Where did they come up with 90 m?” he asked MobileSyrup. “Why couldn’t they go with the American height of 400 ft or 120 metres?” Barnes is frustrated that proximity restrictions to other buildings means he can’t fly over his own home or place of work. He’s also unsure what to make of the “animals” provision, wondering if it includes squirrels. As for the 9km aerodrome rule, Barnes suggests that services like Airmap, can provide detailed guidance on where and when to fly, without imposing specific distance limits.

Comet agrees that the regulations seem heavy-handed. “I’m actually a pilot myself and I don’t think it’s as big of a problem as everyone is making it out to be.” As far as he’s concerned, the biggest problem is with amateur drone operators flying over large crowds at music events, or over crowded city streets, something he says even professionals aren’t allowed to do.

Not all consumers drones are affected. RCDroneArena.com maintains this list of consumer drones that weigh 250 grams or less, and it contains some models that are much larger in physical size than the Mavic Pro. All of them possess cameras, which means that citizens concerned about their privacy won’t be able to use the new laws to curtail would-be peeping toms — this would still need to be addressed by police as matter of criminal mischief.

Drone owners seeking to fight the regulations may have little recourse. Ben Bloom, a lawyer with Minden Gross in Toronto, says the Minister of Transportation has every right to issue rules that “deal with a significant risk, direct or indirect, to aviation safety or the safety of the public.” It’s unknown how many of the 148 reported drone incidents fell under this category.

That’s not stopping some from trying. Vancouver-based Charles Lamoureux, has started a petition aimed at getting Mr. Garneau to reconsider his hardline stance on the 9km airport rule, saying, “The new law is inflexible. Transport Canada has essentially labeled most model aircraft operators and other who fly drones as lawbreakers.”

DJI, in an effort to protect its business and at the same time help drone owners organize themselves to respond to new regulations in the U.S. and Canada, has created the Network of Drone Enthusiasts (NODE) – a site that lists campaigns and other awareness efforts.

Pilots who want to be given greater freedom to fly have no choice at the moment but join the ranks of those who fly drones commercially. Drone pilots can apply for a Transport Canada “Special Flight Operations Certificate,” or SFOC, which is a one-time permission to fly in a designated location, and is a requirement of all commercial drone flights from the simplest real-estate fly-over to the most complex Hollywood shot. Being granted an SFOC is no easy task, Comet warns.

The process can take weeks, sometimes even months, and the prerequisites are onerous. “You need drone insurance, at least two people on your team, you still need to keep 100 feet away from adjacent properties,” he said, and this assumes that you’ve been through a ground school training program and can prove you’re knowledgeable about the many formal aviation rules that govern commercial drone operations. Want what’s known as a Standing SFOC (the ability to fly without submitting an application for each flight)? You’ll need to prove you’ve got a great safety track record — something Transport Canada alone gets to decide, vaguely saying “your eligibility depends on various factors,” on its website.

In other words, it’s something only the most dedicated amateurs are likely to take on.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.