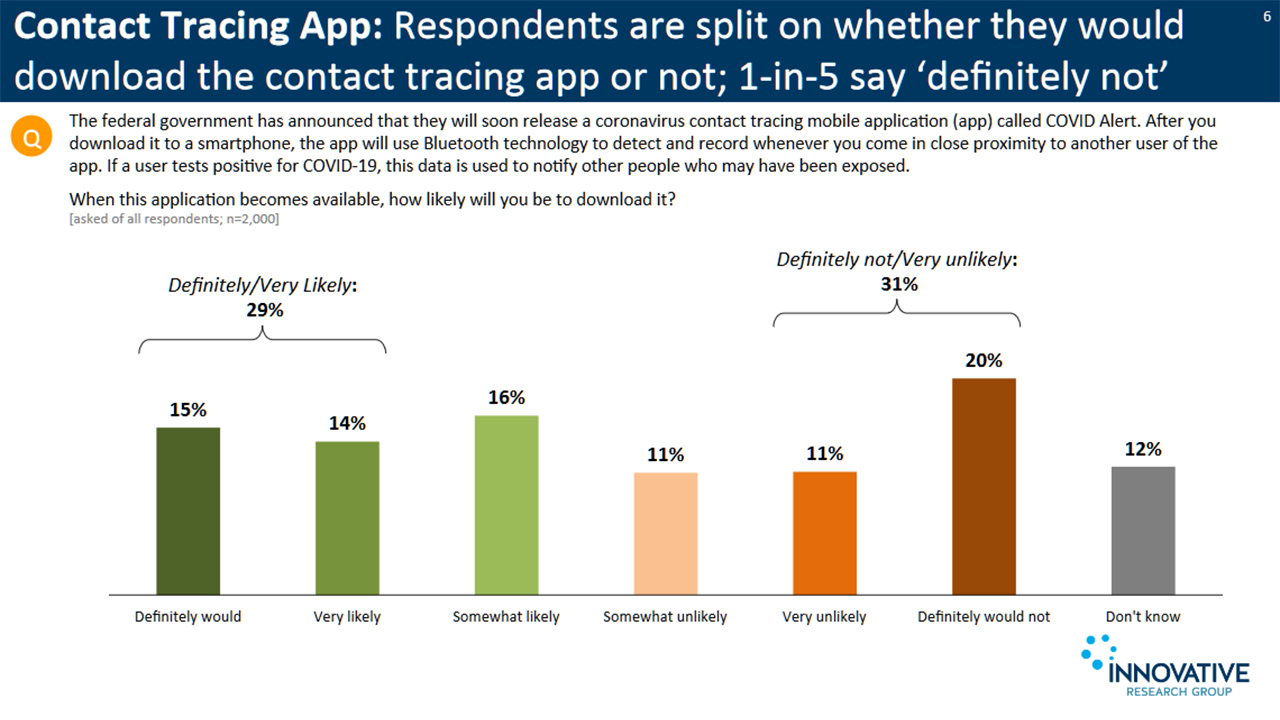

A new Innovative Research Group Poll commissioned by OpenMedia says that 29 percent of Canadians were very likely to download the government’s ‘COVID Alert‘ contact tracing app. Further, 41 percent of people stated privacy concerns were the main reason for lack of confidence in the app.

COVID Alert, initially supposed to launch at the beginning of July, is now making its way through beta testing. It relies on the Exposure Notification API designed by Apple and Google, and the government built the app alongside technology partners like BlackBerry and Shopify.

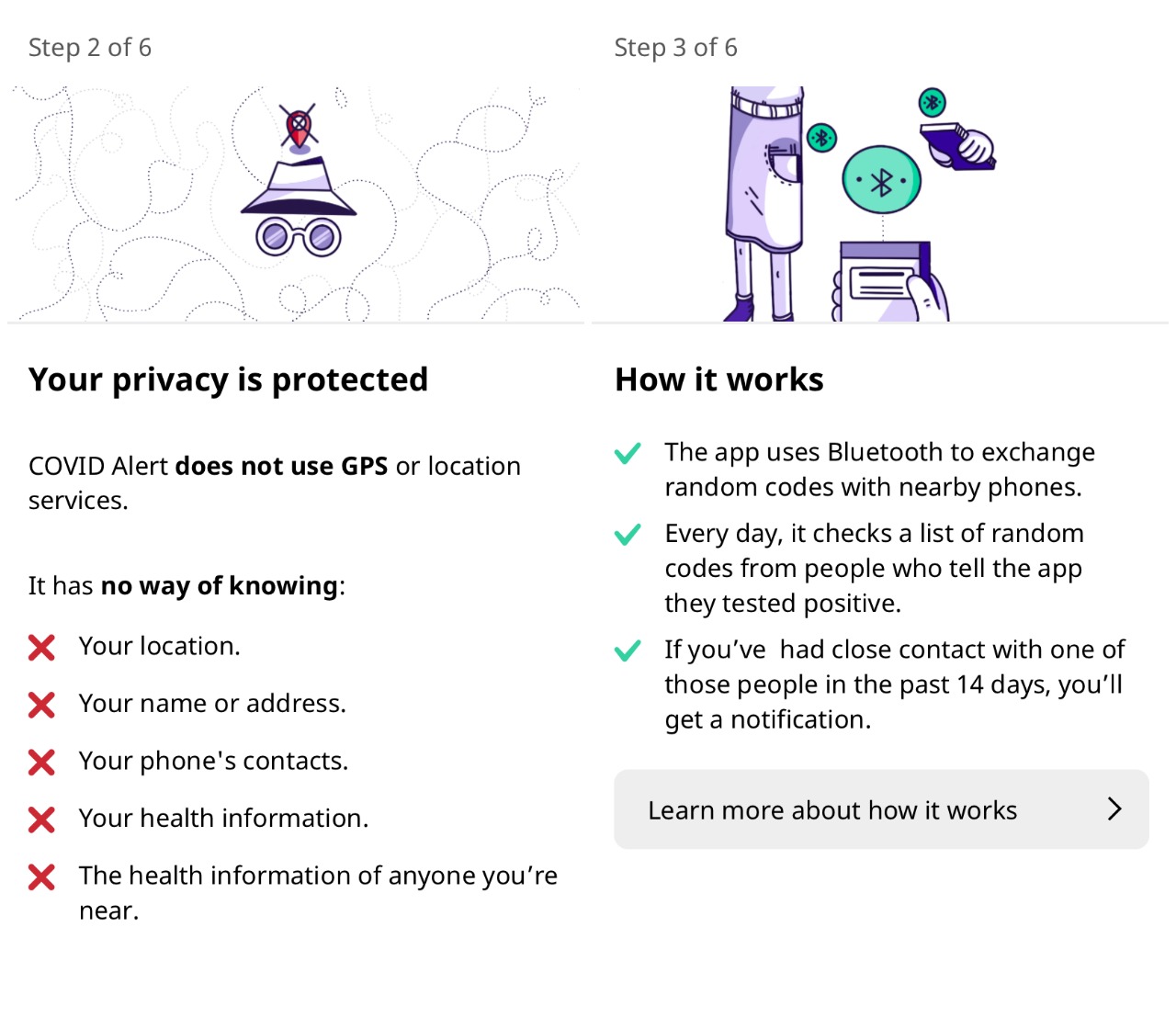

In short, COVID Alert, in conjunction with the Exposure Notification system, works by using Bluetooth to trade anonymous, random codes between nearby devices securely. Each smartphone stores a local, secure record of anonymous identifiers. If someone tests positive with COVID-19, they can use a one-time code provided with their test result to authenticate that result in the app and upload their phone’s list of codes.

Other smartphones check the list for matches and alert users if they were in contact with someone infected with COVID-19. For a more in-depth look at how the system works, check out MobileSyrup’s full coverage of the Exposure Notification system.

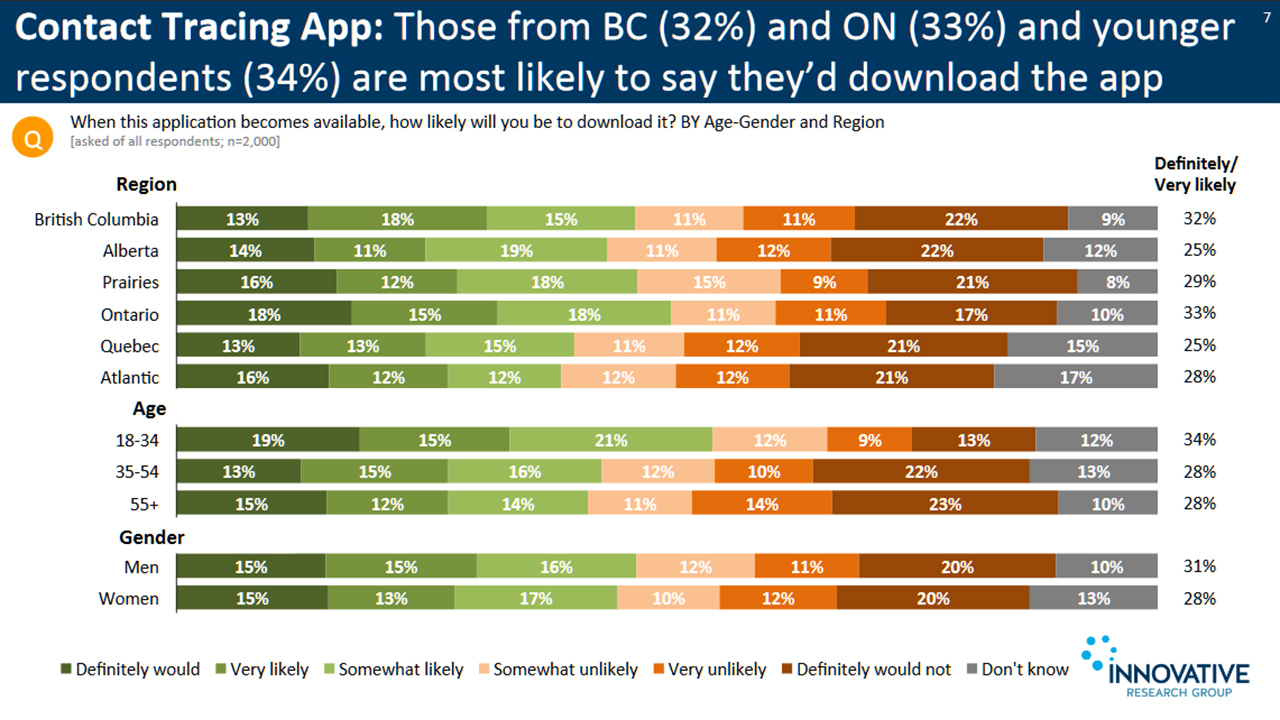

Survey results show B.C., Ontario most likely to download app

Innovative Research Group conducted the survey online using it’s ‘Canada 20/20’ national research panel, as well as with additional respondents from Lucid. Innovative says that the study was administered to a randomly selected sample from the panel and weighted to ensure that the sample’s composition reflected the actual Canadian population.

The total sample included 2,599 Canadian citizens aged 18 years or older. Innovative conducted the study from July 14th to 20th.

According to the survey results, Innovative says that 15 percent of Canadians “definitely would” and 14 percent were “very likely” to download the COVID Alert app. However, 31 percent of people were very unlikely to or definitely would not download the app.

Further, Innovative found that people from B.C. and Ontario, as well as younger respondents, were more likely to say they’d download the app.

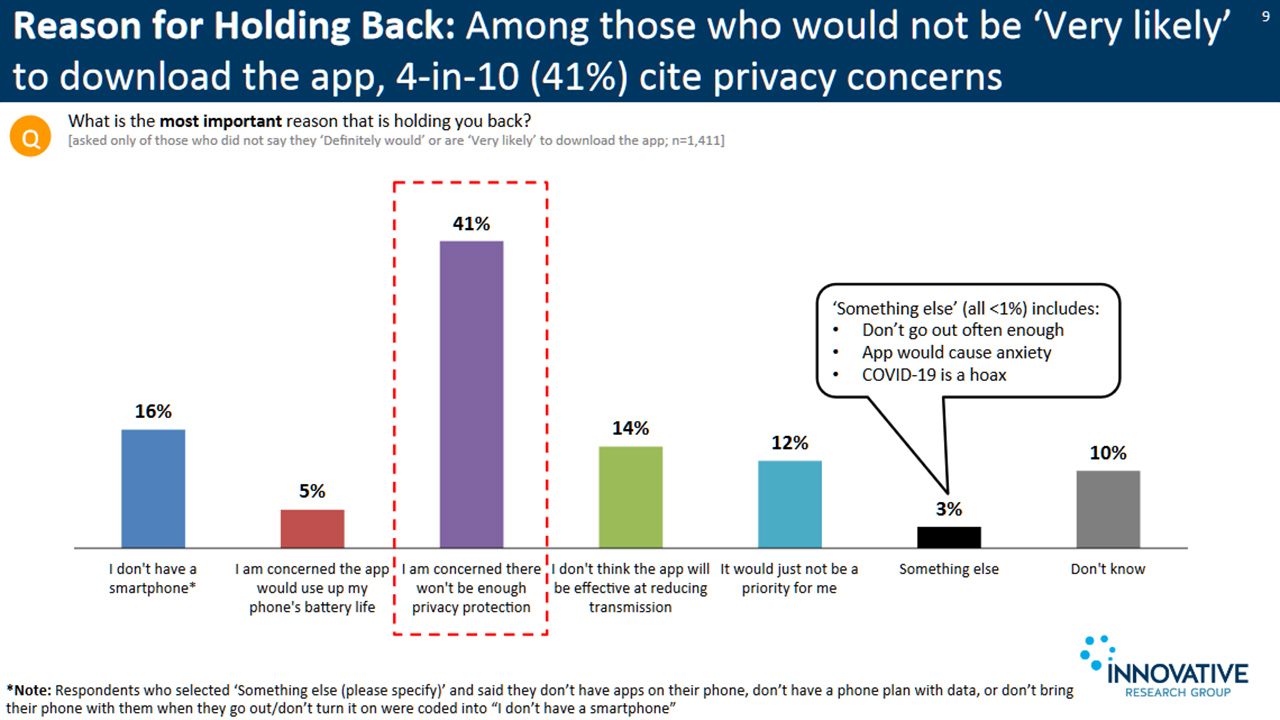

While privacy concerns were by far the most significant reason respondents said they were considering not downloading COVID Alert, it wasn’t the only reason. About 16 percent said they wouldn’t because they didn’t have a smartphone, 14 percent said they didn’t believe the app would effectively reduce transmission, and 12 percent said it wouldn’t be a priority.

OpenMedia pointed out in a press release that privacy concerns are warranted given some of the events of just the last year alone. For example, federal and provincial police forces misrepresented use of the controversial Clearview AI facial recognition software, LifeLabs had a medical data breach that affected 15 million people and Facebook was fined just $9 million for misrepresenting their privacy policies despite a U.S. court charging the company $5 billion USD ($6.7 billion CAD) over a similar issue.

Understanding how COVID Alert works

Still, it’s important to understand what the app actually does and how it works to judge privacy implications properly.

First, the COVID Alert app and the Exposure Notification API are separate pieces of the puzzle. Apple and Google designed the Exposure Notification system to run across the majority of iPhone and Android devices. Since the companies that make these mobile operating systems implemented the API, the Bluetooth communication needed to function can run in the background — something other apps like Alberta’s ABTraceTogether can’t do an iPhone. Further, Apple and Google said they could implement it in a way that doesn’t significantly impact battery life.

All the system does is trade anonymous identifier keys along with some non-identifying Bluetooth data such as the strength and length of transmission. This information can help estimate how far apart people were and for how long they were near each other. It does not reveal who they are or where they came into contact with each other, only that contact happened between two people.

On top of that, the anonymous identifier keys change on a regular basis as outlined here, making it extremely difficult to match keys to a specific user.

As for the COVID Alert app, Google and Apple designed the Exposure Notification system as an API that developers can plug into. In other words, COVID Alert doesn’t perform the tracking, it just uses the tracking system already in place. Additionally, the app facilitates delivery of those results to Canadians through a Canadian system managed by Health Canada.

COVID Alert’s privacy explanation.

As explained in MobileSyrup’s first look at COVID Alert, the app takes the time to explain how it works in simple terms and also notes that it has no way of knowing a user’s location, name, address, phone contacts, health information or the health information of anyone they’re near. As confirmation of this, the beta app installed on my phone has no access to any of the required Android permissions to access that data, nor has it requested access to any of those details.

Finally, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated that the federal government would maintain the database of randomized codes and said that only the government would hold this data.

Trudeau also said that the app is voluntary, but noted that the more people that use it, the more effective it will be.

OpenMedia says that the minimum estimated adoption rate for a contact tracing app to be viable varies between 10 and 80 percent. However, few countries have managed to surpass 15 percent adoption. Further, seven weeks after launch, OpenMedia says only five percent of Alberta’s population downloaded the ABTraceTogether app.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.