It’s weird being with something through its whole life. When my family congregated at the veterinary clinic to put down my Irish Wolfhound, Baron, in 2009, his life as it related to mine flashed in nauseating waves before me.

I remember the way his arcing tail used to smack against the mirror in my front hallway, causing the entire sheet to sway in its tentative moorings.

I still get verklempt recalling the way he used to stand up on the opposite end of our couch only to launch himself like a furry bean bag onto my mom’s lap, where he would lay still for hours as we watched television and drank rooibos tea. He always plays a central role in these memories, even if, most of the time, he was in the background, lying nearby, waiting for us to love him. I loved him then and I love him still.

It’s weird that I feel the same about a streaming music service.

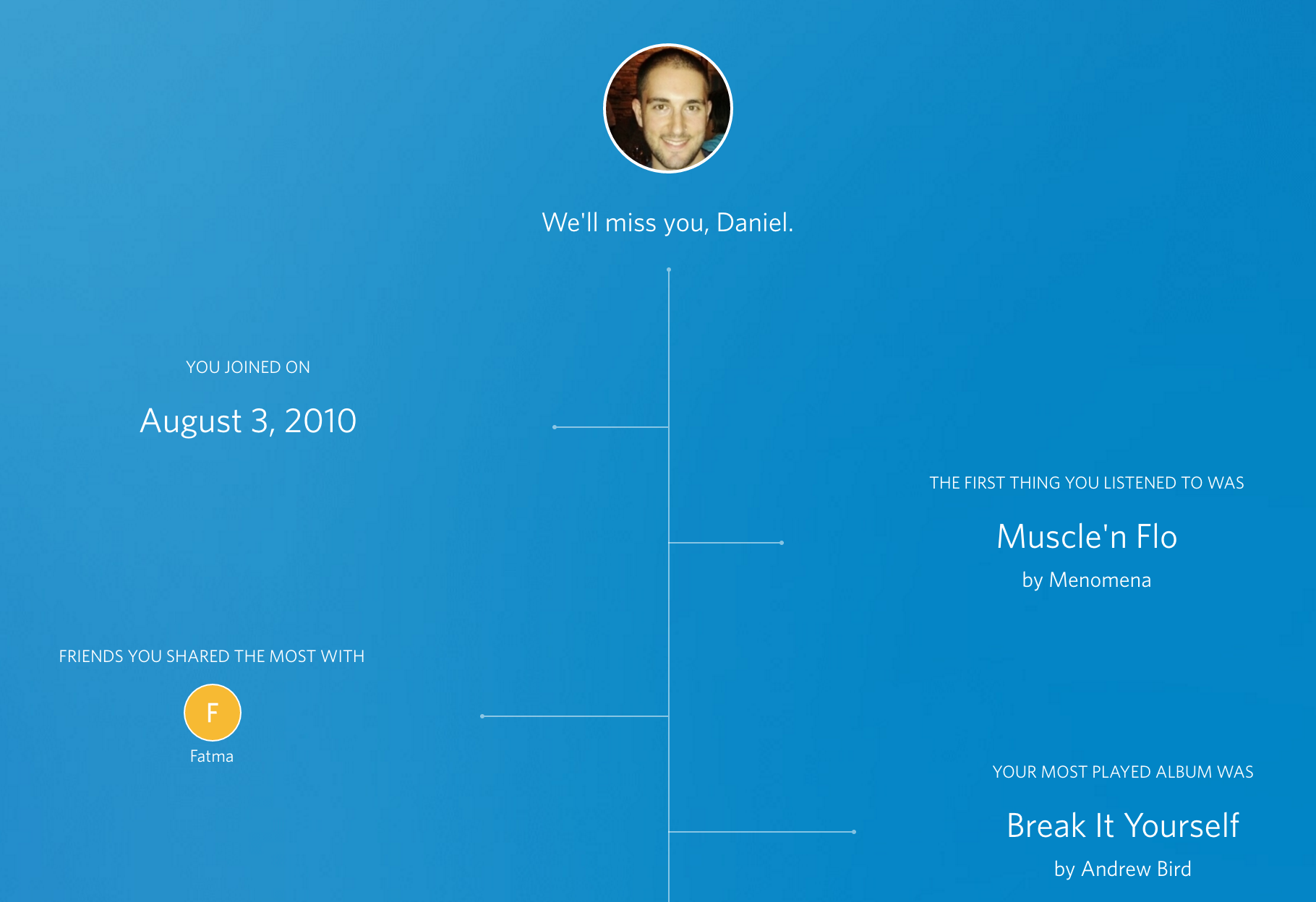

I joined Rdio the day it launched, on August 3rd 2010, and I listened to it nearly every day since. Even in its infancy, when Spotify was years away from launching in Canada and Google and Apple were still shaving layers off their respective mobile platforms, Rdio felt fully-formed, like it had always been there.

I joined Rdio the day after my favourite album of 2010, Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs, was released in Canada, but the band’s label, Merge, didn’t make it available on the streaming service for over a year.

In the interim, the album’s Rdio listing filled up with comments decrying its lack of availability — “How could a top Canadian artist not be available in Canada?” they cried, and I drank it in — the first of many hours I’d spend scrolling through what would become my favourite social network next to Twitter.

There were surprises like this peppered throughout my experience with Rdio. How it would, before any other service came close, be able to suggest albums and playlists I would end up listening to for months. I would listen to my friends’ playlists and learn more about them, and share unique links on Twitter only other Rdio people could consume. It was the ideal community, full of support and discovery and, best of all, music.

Because it was the first streaming service of note to come to Canada, for many early adopters like me Rdio existed as a hat-tip, a closed nod to others in the community, and an impulsive recommendation to those without. “Have you tried Rdio yet?” I’d ask, and they’d say no until they, one by one, said yes.

Rdio’s core functionality always prioritized design over features, which was as much a benefit at its inception as it was a detriment towards its end. The company was one of the first to promote white space and clean, sharp typography at a time when Retina was a term barely used outside tech journalism. It implemented a left-side sliding menu in its mobile apps long before it was standard practice. And, perhaps most importantly, despite its seemingly-boundless library of singles and remixes and live albums, it honoured the album better than any service I’d used before, and used since.

It was clear Rdio was in trouble when, despite innovative engineering feats and relentless attention to design minimalism, Spotify kept getting all of the press. We Canadians were somewhat shielded by this fact, since until Spotify’s Canadian launch some four years later there were few true competitors. Deezer and Slacker had been around for some time without making an impact, and Google Play Music launched to middling reviews, but I rarely heard of anyone giving up their Rdio subscription until the end of 2014, when Spotify did here what it managed in every other market: to suck up all the air.

Somehow, even as Spotify stole more of my time with its insanely-good Discover Weekly playlists, I always returned to Rdio, to the life I built within its comforting blue-and-white walls. When the company launched new features, like personalized radio stations or recommendations based on listening history, I altered my habits slightly, spending more time in sections I knew would eventually lead to the company’s demise. Each expansion further mired the core product in complication, and reinforced just how fully-formed it was upon its debut in 2010.

Earlier this year, when the company launched a baffling new $3.99 tier called Rdio Select, it became obvious to me the company wouldn’t last much longer. It had already taken investment from US terrestrial radio giant Cumulus, which allowed Rdio to launch free ad-based streaming and, later, with Shaw, to localize commercials and fashion a wider distribution berth for the Rdio brand in Canada. The product itself hadn’t fundamentally changed, but there was an ominous patina of grit just underneath the surface.

My best memories of Rdio are not of its minimalist design or its feature set, but the way it simply made music into a tool that could be manipulated to suit my particular mood or situation. But instead of dehumanizing the artists or commodifying the songs, Rdio managed to find a balance between emotion and utility.

I will miss Rdio. Even as I have gently tapped the competition, owned by giants, I have preemptively mourned today, the day Rdio disappears. There is something strange about this, too: despite having exported my playlists and favourite artists, this digital death is most acute because my emotional connection to Rdio is tangible and human and all about that evening in August, and the four Augusts since, when it was in the background, lying nearby, waiting for me to love it.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.