Sitting here comfortably in 2016, it’s easy to take for granted just how much smartphones have changed the daily lives of so many Canadians.

Sure, most of us are more distracted than ever, and it can be easy to feel bogged down by a seemingly endless stream of notifications, calls and text messages that come with owning a mobile device. But the benefits smartphones bring to our life are innumerable — you can’t get lost with a data connection in 2016, for instance.

For the time being, however, there’s one industry that hasn’t succumbed to the massive tidal wave that is the mobile economy.

Unlike transportation and house, two industries that are experiencing massive upheaval thanks to apps like Uber and Airbnb, healthcare, especially the administration of it, remains stuck in the era of the paper and pencil.

One of Canada’s most successful entrepreneurs, Mike Serbinis, the founder and former CEO of Kobo, is trying to change that with his latest startup Toronto-based League.

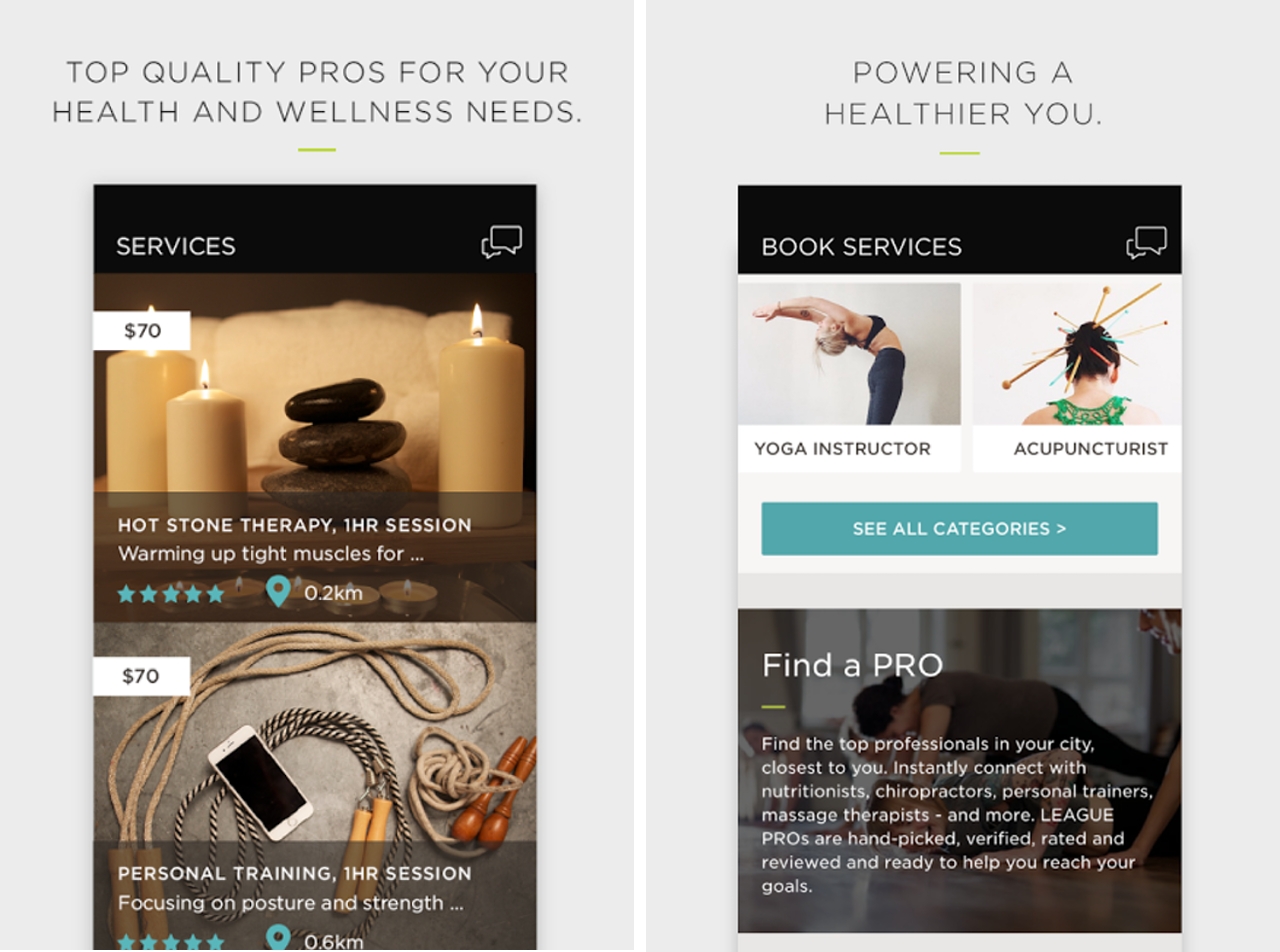

About a year-and-half ago, when Serbinis first started showing off League to people, it was a mobile app for connecting consumers with wellness professionals in and around their local area.

Much like with apps like Zocdoc — which has since changed focus, as well — people could sign up to the platform and use it to schedule appointments with a variety of wellness professionals, including massage therapists and acupuncturists.

League has since evolved into a platform that allows companies to administer their employee healthcare plan using a digital wallet. The personal healthcare component is still there, but it’s the business-to-business aspect of League that has the most potential to add value to the lives of Canadians.

And it comes at a critical juncture.

The need for someone — anyone — to disrupt how healthcare benefit plans are administrated has never been more pressing. This past September, Statistics Canada published a report that said there are now more people in Canada over the age of 65 than there are individuals age 15 and under. The combination of a massive aging population and the increased prevalence of preventable diseases like diabetes type two will result in drastically increased healthcare costs over the next few decades.

In Ontario, for example, already 40 cents of every tax dollar is spent on healthcare. Within the next decade or so, the amount the province spends on taking care of its sick is expected to escalate to 70 cents of every tax dollar, according to Serbinis.

In the private sector, healthcare costs are likewise expected to become untenable.

In the U.S. and Canada, the average employer-sponsored health benefits plan todays costs between $10,000 and $15,000 per head. The same factors that will cause public healthcare costs to increase will result in companies paying more to take care of their employees healthcare bills. For companies that depend on a five to 10 percent profit margin be profitable, they will either need to stop offering their employees a healthcare plan or go out of business.

“We’re at a tipping point,” says the former Kobo CEO.

The light at the end of the tunnel is that costs can be reduced, and they can be reduced without impacting the quality of care people receive at their doctor.

With a traditional health benefits plan, it can cost between $10 and $20 to administer something as simple as a $150 dental cleaning. On League, employees can pick a dentist, schedule an appointment and go to get their teeth cleaned. At the end of the process, money automatically changes hands.

Companies that use League to administer their healthcare benefits plan pay a small administration fee, whereas the insurance providers pay a 2.5 percent transaction fee. Consumers and employees, however, don’t pay a single cent.

“That model that can move money from a health benefits plan for less than a hundredth of the cost turns out to be pretty disruptive,” says Serbinis.

Since launching this part of its platform in Toronto and Vancouver, as well in Seattle and Boston, Serbinis says his company can’t keep up with the amount of companies and insurance carriers that want to work it. Within the year, the company plans to launch in other major cities throughout Canada and the U.S.

For Serbinis, League also represents a chance to surpass the heights he achieved with Kobo. Despite the fact he successfully exited the company when it was acquired by Rakuten in 2012 for $315 million, talking to him several years after the fact there’s a sense that Kobo was a missed opportunity.

“You like to compete against big, dumb and slow. We didn’t have that at Kobo, we had Amazon,” he says. “Jeff [Bezos] was a relentless competitor.” One particular episode that stands out in Serbinis’ mind was when Kobo was preparing to announce it was set to launch in Brazil. Amazon pre-empted Kobo’s announcement by issuing a press release that said it too was launching in Brazil. That same day Amazon updated the amazon.com.br website with a tagline that said, “Kindle. Coming Soon”. There was no release date or price mentioned.

“We’d lose some wind in our sails because of [Bezos],” says Serbinis.

The spectre of Amazon informed a lot of the decisions Serbinis made during his tenure at Kobo, including the choice to sell the company to Rakuten. In its first year, Kobo recored sales exceeding $100 million. Going into its second year, the company projected sales to increase to between $200 and $300 million.

With Kobo, however, the issue was so much of the company’s revenue was tied to manufacturing a hardware product — between 70 to 80 percent, according to Serbinis. Amazon, on the other hand, could turn to its other revenue generators, including its web services business (AWS) and e-commerce store, if it decided the e-book market wasn’t going in its favour. It’s ace in the hole, as it were, was that it did not depend on the Kindle to be profitable.

“Ultimately, the nuclear warhead threat that was Amazon — Jeff Bezos could press a button and drop the price of the Kindle, rendering all our inventory dead — was a real and present danger,” says Serbinis. “Selling Kobo was the choice that we had to take to continue growing the company.”

“In this world, it’s different,” he adds. “It’s a huge market for the taking. Carriers like the Sun Lifes and Manulifes of the world could become partners. It’s what I did at Kobo. I picked a partner in each country and went after Amazon — the enemy of my enemy is my friend. We could the same here and get big fast.”

Serbinis compares it to competing in an Olympic demonstration sport. “There’s no guarantee that it will make the next Olympics,” he says. “Likewise, it might be a tech category no one cares about, but no matter what it’s global and there’s a podium. There will only be three people on that podium; you want to be one of the top town because no one ever remembers number three.”

“I want to build this to be giant and I think we can.”

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.