Canada is remarkably good at rallying around its stars, and just as adept at abandoning them.

In the technology sector, before it was trendy to dismiss BlackBerry, née RIM, it was a cultural darling, the type of phone — and employer — you boasted about to friends and family.

The exact date of The Turn is unclear, but the company began losing its cachet amongst consumers as the gulf between software experiences widened between BlackBerry OS and its main competitors, iOS and Android, sometime in 2011. As Apple and Google piled huge resources into outfitting their devices, or their partners’ devices, with touch-friendly features, and apps that took advantage of the latest in hardware developments, BlackBerry piously stayed the course, until it no longer could.

When it became clear that BlackBerry was building a new operating system based on the extremely powerful QNX kernel, few thought it was an inherently bad idea, but many saw the harsh reality of entering a market, in early 2013, in which two very powerful leaders, Apple and Google, and a stubborn third, Microsoft, practically owned the market. That BlackBerry tried and failed to pursue its own software strategy is a well-known mark against saturation, something Palm learned four years earlier: a strong foundation is not enough to fell the behemoths that, for better or worse, have the industry’s developer community, and all of the buying power, behind them. Even in January 2013, when BlackBerry unveiled the Z10 and Q10, it wasn’t clear how the company would sell enough handsets to keep them profitable. And they didn’t. For many quarters thereafter, legacy BlackBerry OS devices outsold their BlackBerry 10 counterparts. When the Z10 and Q10 were succeeded by the Z10, Q5, and eventually the Classic, Passport and Leap, BlackBerry was recognizing revenue from under a million devices per quarter.

In many ways, BlackBerry 10 is superior to Android. It was, like iOS, built with touch input in mind, only later being rejigged for navigation with the Classic’s trackpad or Passport’s touch-sensitive keyboard. Its Hub, which the company is bringing over to the Priv in some form, is an excellent way for people to interact with email, texts and, to a lesser extent, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn messages. And it’s unimpeachably secure, a stalwart enemy against malware.

But the native developer community never showed up. And as iOS and Android shored up their consumer-friendly feature sets, BlackBerry got left behind. When it did add interactive notifications, a flatter, more modern colour palette, and support for Android apps through the Amazon Appstore, the company was under one percent market share in the United States, and support was quickly dwindling for its homegrown devices in Canada. This happened despite relatively warm recognition for BlackBerry’s technical achievements on devices like the Z30, Passport and Classic, well-made and utilitarian devices let down by an increasingly barren app store and a tension within and without on how the company would approach its handset business as it focused on enterprise software and security.

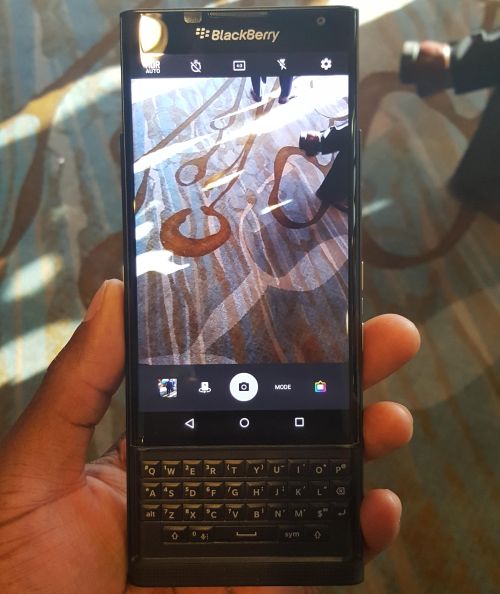

It was little surprise, then, we eventually began hearing the whispers of a new class of BlackBerry, one outfitted with Android. And when the company revealed the slider back in March, the one that would eventually become known as Venice and then, officially, Priv, we always suspected there was something special about it.

Much of the ballyhoo around the Priv has focused on its keyboard, but I suspect that will be one of the less important aspects of the device. The world has moved on, and for all of its tactile benefits, the QWERTY keyboard marks but a fraction of the industry’s priorities. The intrigue surrounding the Priv reveals itself to a kind of curiosity, a nostalgia for the time when BlackBerry made the best products — or an approximation of what we considered to be the best — and fulfilled the communications needs of dozens of millions of people.

That the Priv runs Android doesn’t immediately make it a good phone, but by giving up some of BlackBerry 10’s well-received idiosyncrasies for Google’s well-stocked Play Store is, in most peoples’ minds, a fair trade. Moreover, Google worked with BlackBerry to certify the Priv for use with its Play Services, giving the Waterloo company for the first time unfettered access to Google’s suite of services like Maps, Chrome, Hangouts and more.

The curiosity with people are approaching the Priv exceeds that of a regular high-end Android smartphone, but that’s because so little actually new has come out of the camp for so long. The industry is mature, and the players set; for all the improvements in performance, efficiency and optics, most phones are mere replicas of two Platonic ideals. On the one side sits the Nexus, pure and lightweight; on the other, Samsung, ostentatious and bloated. But the two sides are converging, with Google pegging features from its OEM partners, and Samsung reining in its excesses, its latest smartphones a panoply of restraint from the Korean giant.

Where does BlackBerry fit into this wider picture? After the swelling masses have digested and execrated their Internet feelings on the Priv’s form and function, and the reviewers have moved on, how does BlackBerry navigate this swamp of a market? At least when it controlled both the hardware and software it sat apart, peering in like a proud and headstrong ideologue.

But within Google’s world, where Samsung basically owns the North American market and companies like LG, Sony, HTC and Motorola lap up the remaining few points, does BlackBerry hold any cachet? And will a focus on security, something that has only marginally affected Android’s reputation in the wider consumer market to date, despite regular opportunities for derision and despair, aid the Priv’s cause? Android is not an insecure operating system, and devices that are regularly updated (read: Nexus phones) are amply fortified to deal with real-time threats as they arise. All of BlackBerry’s kernel-level anti-tampering security will be for nought if it can’t manage to keep its operating system updated, or if it imitates its Android peers by abandoning the Priv only months after launching.

I’ve asked a few Canadians with close ties to BlackBerry, either because they used to work there or knew people in the Kitchener-Waterloo area that did, whether they think the Priv is a desperate attempt to claw back the market share it lost over the past four years, or if this is a well-executed strategy by John Chen to promote BlackBerry’s suite of software and services in a number of markets that wouldn’t have otherwise considered working with him. Most said that the Priv was in the works for a long time, since shortly after Chen came to the company in late 2013 and, like Nokia, toyed with the idea of releasing an Android phone for years prior.

A number of things have happened since then. Android phones have become less expensive to manufacturer; Google has drastically improved the Android experience, from usability to aesthetics to security; and BlackBerry has transitioned to a multi-platform organization, recognizing internally, like Microsoft did at an equally crucial time, that iOS and Android were necessary parts of any future product strategy. Whereas Microsoft has re-approached the smartphone market, and the developer community, by making Windows 10 as ubiquitous as possible, BlackBerry is tacking its horse to the only logical compatriot. It is hedging on its customer base wanting the best specs with a price to match. It is hoping that people recognize the brand, and either out of fandom, curiosity, or a sense of stomach-pinching loyalty, choose the Priv over any number of other equally-compelling choices.

How far can nostalgia carry the Priv? It will manage to get people in the door, which is quite a bit closer to the cash register than BlackBerry has been in some time.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.