It’s been a long journey for Andrew Shouldice.

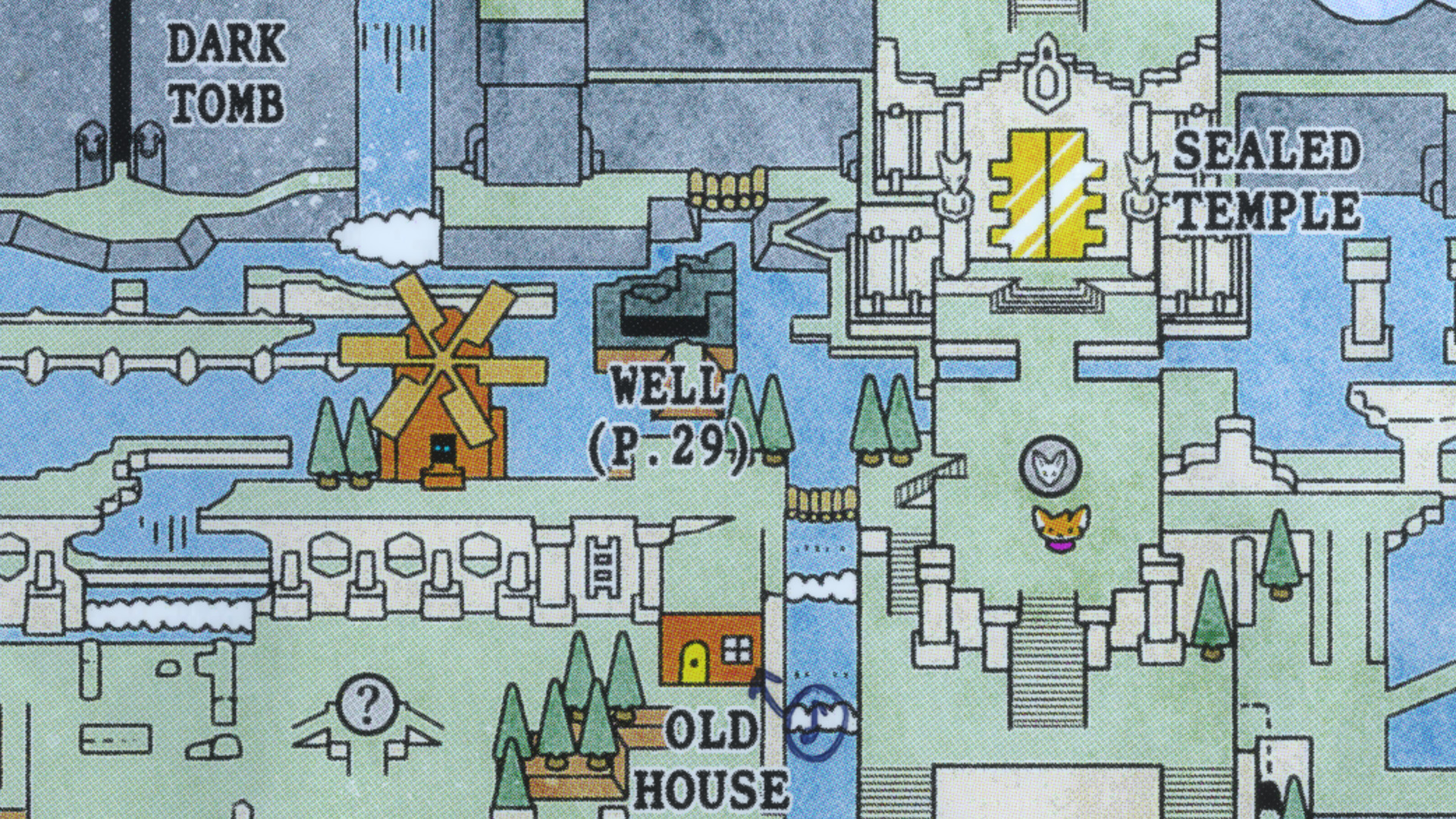

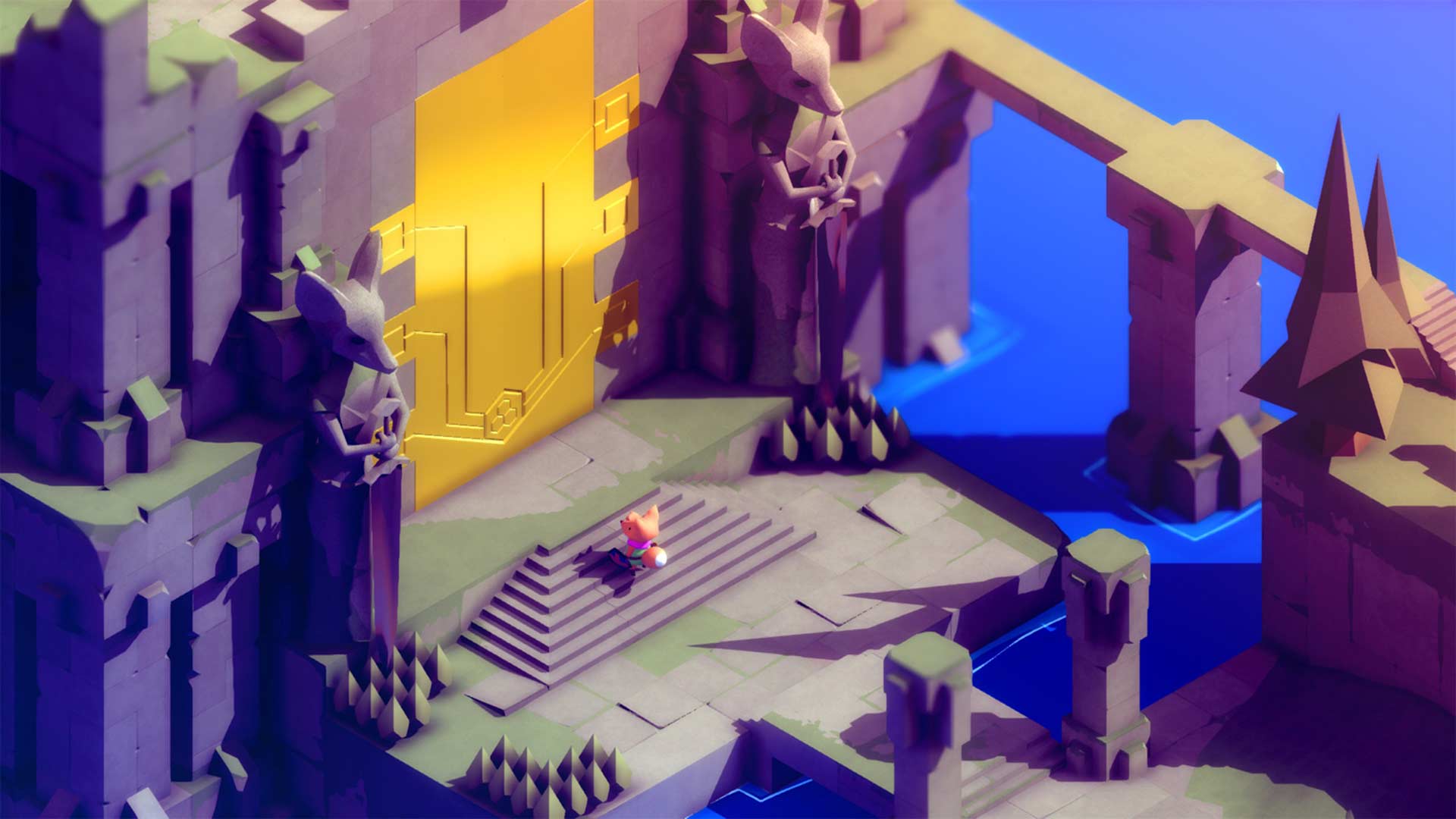

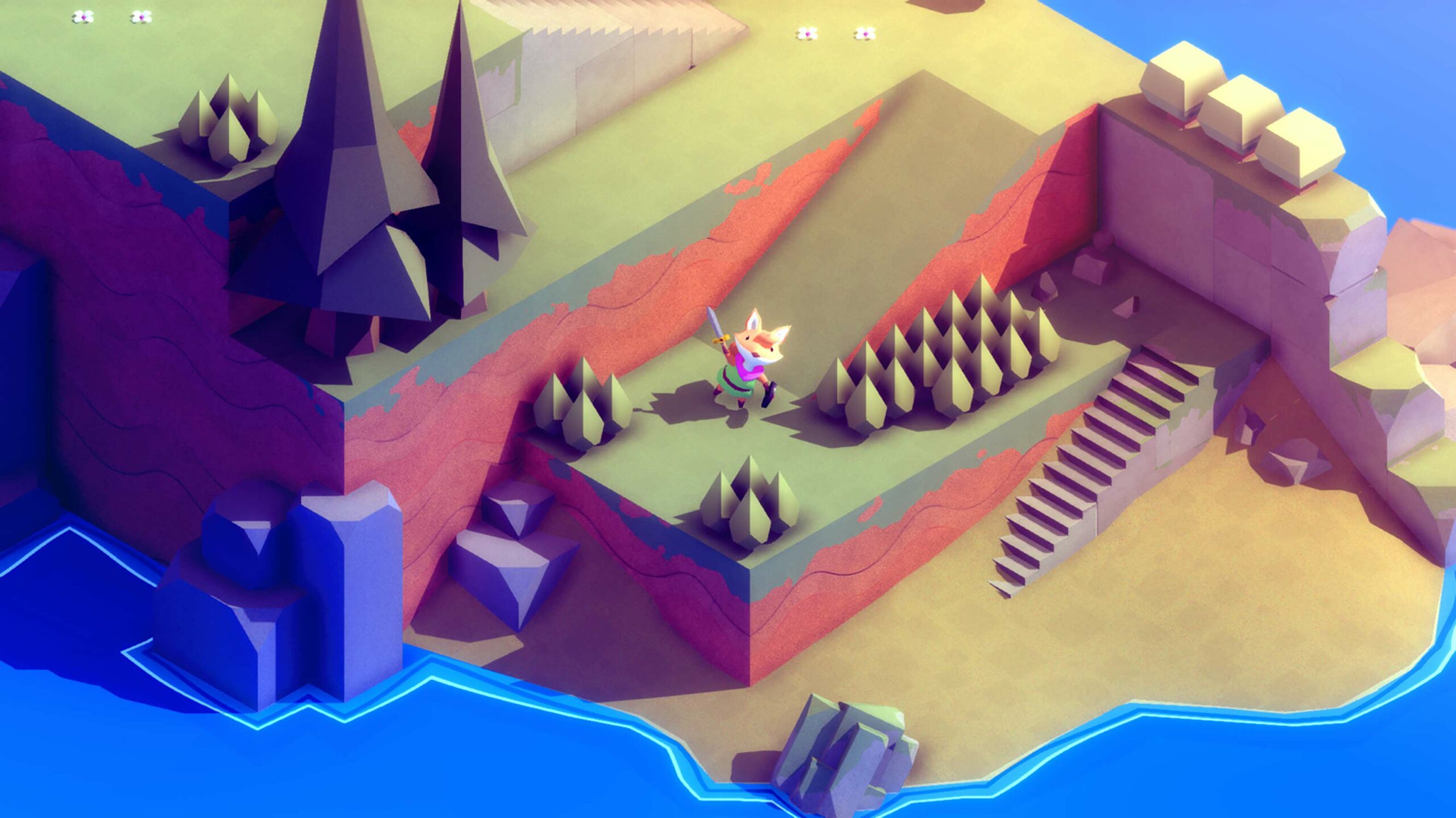

After working at Halifax-based Silverback Games for six years, he departed in 2015 to go indie and make an adventure game in the vein of The Legend of Zelda. Formerly known as Secret Legend before being renamed Tunic, the game follows an adorable little anthropomorphic fox as he explores a mysterious land. It’s so mysterious, in fact, that pretty much all of the in-game text is written in a foreign language. As the fox, you’ll need to recover pages of an instruction manual and piece together your quest.

It was a pretty risky decision to rely so much on the player to figure all of this out for themself, but thankfully, it paid off. Upon its release in March 2022, Tunic garnered rave reviews for its world and puzzle design, boss fights and more.

With that long development journey behind him, Shouldice sat down with MobileSyrup to provide a post-mortem on the game. Joining him was Kevin Regamey, creative director at Power Up Audio, the Vancouver-based development house that’s worked on hit indies like Cadence of Hyrule, Celeste, Into the Breach and Darkest Dungeon 2. In addition to sound, Regamey and his team helped Shouldice with other aspects of Tunic‘s design, including the creation of the fictional in-game language.

Together, the pair talked about inspirations, the work that went into making a game over such a prolonged period, how they balanced difficulty and the lessons they learned from the whole process.

Note: this is a spoiler-free discussion about Tunic.

Question: To start, what’s it been like to finally have the game come out? This was, for you, Andrew, a seven-year journey. And then Kevin came on a little later. So for both of you, especially Andrew, what does it mean for you to have the game released and the response so positive?

Andrew Shouldice: The moment when I realized that people really liked it was emotionally profound, let’s say. But now that I’ve sort of had a chance to absorb it, it’s a bit of a relief. I wish I could go back in time and tell myself that all those moments when I was 100 percent convinced that it was a tire fire that everything’s gonna be okay. And Kevin, actually — you’ve been on it for just about as long, right? Because it was only a few months into development in 2015 that we had crossed paths.

Kevin Regamey: Yeah, you hit us up at Power Up in, I think, April 2015. Yeah, we’ve been [on Tunic] for a while, too. [laughs]

Q: You’ve been asked many times about Tunic‘s clear The Legend of Zelda inspirations, so I wanted to take that a bit further. We’ve heard stories about how Zelda creator Shigeru Miyamoto was inspired by childhood adventures in the wilderness of Japan. I’m curious — did you have any similar experiences in the Canadian outdoors?

Shouldice: Yeah, totally. It’s embarrassingly similar to that Miyamoto story, actually. I remember mapping out the park near where I grew up [in Halifax] — near one of the canals — and sort of dividing it into sections. And there was this weird section of pipe that you could crawl inside. And here’s the place where the big rock with fire ants are. And there’s the lake on this side, and here’s where chickadees will eat seeds out of your hand. And so that feeling of ‘it’s a big, wide, open space with all kinds of cool stuff, and you just want to run as fast as you can to see what’s next’ — I like that. I don’t know if I was thinking specifically about that [with Tunic].

I mean, there are definitely times when I was walking through that very same park as an adult, taking notes and trying to recapture that same feeling. But I think that emotion definitely is something that carried through. And, of course, playing games like The Legend of Zelda and Fez and things like that definitely also influenced it. Listening to the music of [Tunic co-composer] Terence Lee, Lifeformed, when I was first getting started on the project also sort of helped colour my feelings — at least at the beginning — about what the game was going to be about. Kevin — have you got inspiration thoughts as well?

Regamey: Nothing quite like walking through the park in my childhood.

Shouldice: [laughs]

Regamey: I haven’t even heard that answer before, Bradly. What the heck! [laughs] This was new to me, too, about this park.

I’ve always kind of gravitated, my whole life, towards the kind of games with a ‘what’s underneath this rock’ kind of thing? Like you’re always poking around every corner. I recall playing Commander Keen in CGA [Colour Graphics Adapter] graphics on my home computer, and that game’s secrets were so ridiculous and arbitrary, but they rewarded poking around in such a great way. I saw someone on the Steam forums complaining about Tunic — how this game was like, ‘Oh, I can’t believe they demand you to poke in every corner. This is like ‘Walking Into Walls: The Game.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, totally — isn’t that fun?’ [laughs]

I love that kind of gaming. In Commander Keen, any given wall you look at might be non-solid. It was so arbitrary, but it was like, ‘oh, man, I found another one, that’s great!’ I like to think that Tunic is a little more than ‘Walking Into Walls: The Game.’ But just the idea of poking around — I think that was a lot of what we tried to push into the audio side of things as well — trying to hide things here and there. And I think that we’ve done okay at that, too.

Q: Since you were both there from the start — what’s it like to work on a game for seven years? On the one hand, you’re in the unique situation where your game has been in the public eye and demoed on show floors for a while now, so you get that feedback. But on the other side, that’s still a very long development cycle. How did you pace yourself during that and plan everything, especially as ideas may have evolved over time?

Shouldice: I can start, but maybe Kevin can answer from the perspective of having shipped games in less time as well. Whereas this is sort of my first major project, so I can’t speak as much on that. But it had iteration. I think the reason that the development period was long was, first of all, that it’s a very small team. And it’s a relatively large, complex game. But learning along the way was a big thing — iteration, figuring out what works, discovering what the game is and wanted to be.

And also, because it started very small, the very first sort of, ‘hey, I’m working on a video game’ was on Vine — just sharing with friends, basically. ‘I’m working on this thing. Hey, you want to show it at your event? That’s awesome. That’s so cool. That’s a huge deal.’ And then that slowly ratcheting up as more and more people found out about it. Like [being] a part of the Xbox stage presentation at E3 2018. Like, ‘wow, yes, of course, we want to do that, even if the game is not ready yet. What an amazing opportunity.’ So it was just sort of this slow process of refining the game itself and being presented with these amazing opportunities. But Kevin might be able to contrast that with things with less protracted development.

Regamey: You use the word “pacing,” Bradly. I don’t think that we started in 2015 and said, ‘Okay, here’s the plan for the next seven years — here’s our roadmap.’ [laughs] That wasn’t quite the move. It’s a bit different, certainly. I’m not sure if you know — our team is Power Up Audio. We’re third-party and we’ve worked on a variety of games. And before our current company, my partner, my co-founder and I, worked at other third-party companies. So the two of us together worked on like hundreds of different kinds of games. And we’ve shipped a lot of stuff and sometimes work on a thing for four days. Like some mobile games, they need 12 sounds, then we’re done forever. So it’s a very different kind of thing than many, many years. And even comparing to larger projects like Darkest Dungeon or something — taking three years to finish that kind of game.

Being in the position of a third-party company like ours — like a vendor, basically — we certainly view ourselves as deep collaborators. We want to throw ourselves into the game as much as possible, but we’re also faced with deadlines. Like, ‘what is the most blazing fire right now? We’ll put that one out first.’ So with a game like Tunic, it was a matter of weighing in as often as we could, while kind of dealing with other obligations. And because there’s so much iteration and trying to like find the game, like Andrew’s saying, that would mean things get trashed sometimes or heavily changed or something. And what that led to was a lot of audio development.

It ramped hard towards the end naturally, because everything’s kind of congealing and coming together. And it’s like, ‘oh, this is a concrete project now, now we can put things in.’ And when you’re working down the task list — ‘this is actually not gonna get trashed, in all likelihood.’ So it was a lot of — as far as pacing goes — leisurely walking towards the beginning, and then a sprint at the very end. That’s often how it goes for audio for any game out there. I’m sure you can ask anyone in sound in games and that’s often how the story goes.

Q: The subject of difficulty has been especially prominent over the past few months thanks to Elden Ring, which released shortly before Tunic. People were talking about how that game doesn’t hold your hand, and Tunic doesn’t spell things out, either. At the same time, you offer some options for players: invincibility and infinite stamina. That’s more on the combat side of things; the player doesn’t have much guidance in exploration. With all of that said, how did you ultimately balance Tunic‘s difficulty?

Shouldice: It’s a challenge for sure. And a lot of the time, it’s very hard to test that sort of thing, because you can really only test a puzzle, truly, once per person. So we have to sort of build up an intuition for what works and what doesn’t. But I feel — and maybe this is pie in the sky thinking — that the ideal scenario is that something like that is not too finely designed. That there are some rough edges on the puzzles side of things. Maybe this is a little bit too tricky, and it’s going to require a community to figure out. Or maybe there’s a sneaky way that you can solve this riddle in a way that wasn’t intended. And that’s an exciting feeling as well. The core of the game is about uncovering mystery and feeling like you got away with something. And so having a spectrum of, I guess you’d call them ‘difficulties,’ makes a lot of sense.

As far as combat difficulty goes, including a ‘No Fail’ mode was a very easy decision to make. Because it just allows a broader audience to appreciate the parts of the game that they like — people who enjoy combat challenges are not going to touch that option, probably. And for people that are less interested, it’s there for them if they want it. And one of the intentions was that if someone didn’t really want to engage with the combat that deeply, they could still get an ending to the game and have a satisfying experience. Also, if someone wasn’t especially interested in delving deeply into the late-game secrets, they could also have an ending.

And I think that it’s not just a nice thing — a ‘warm, fuzzy, more people get to play the game’ [thing]. It also means that there are people who will know that there’s a little bit more, if that makes sense. Like, the best experience in a game is realizing, ‘Oh, there’s more here than I thought there was.’ And so exploring a world and you didn’t even know there were puzzles — let’s say you’re not much of a puzzle person, but you start to realize that they’re there and you think, ‘Oh, wow, what else is in this game — this whole other part of it that I’m not even engaging with?’ And maybe that tantalizes them and they want to get into it? So that’s special to me.

Regamey: Andrew also just wouldn’t share anything with me ever. [laughs] Myself and the rest of the team, I’m sure, were often just the guinea pigs. Because like he was saying, you only test puzzles once. So there would be times when these different kinds of puzzle pieces of the world were being developed in some isolation — different scenes in unity and such. And then it was kind of a matter of like, ‘Oh, we’re gonna get this one right here, there we go.’ And perhaps I haven’t played through that particular transition from A to B — the full kind of “playthrough” of the game. And at A to B, I’m like, ‘I have no idea where I’m going.’

Shouldice: [laughs]

I’m completely stuck. And it turns out there’s a little pathway that I just didn’t see and it’s ‘critical path.’ It’s like, ‘oh, we should probably shine a little light there or something just a little more.’ So you’re right: it’s really challenging to know exactly where that cusp is between being too obscure and too demanding that you poke around every corner. And being too, ‘here’s this text on screen, have you tried walking down this corner here instead?’ Like, we don’t want to be quite like larger companies that are very ‘spoon-feedy’ about the problems. Myself, I like suffering for a while and finally getting that realization — like, ‘oh, I solved the puzzle.’ And sadly, some of the games I play sometimes will tell me within, like, five minutes of effort, ‘hey, you should put that block on that button, eh, player?’ [laughs] We tried to trust the player as often as possible. And yes, it led to some pain points here and there but we tried to smooth those out as much as we could.

Q: This is for Kevin, primarily, but feel free to chime in, too, Andrew. Since Tunic doesn’t have a traditional text-based story or voice acting, you have to rely more on elements like the fictional in-game language you helped design, and, more specifically, audio cues and the like. From your perspective, how do you even approach designing audio for a game like this?

Ragamy: Yeah… It was a choice very early on to have the fox be silenced, kind of [Half-Life protagonist] Gordon Freeman-style, where you have the player as the fox. We didn’t want to imprint any kind of personality or gender identity or anything on the player. Just — you were the fox. I recall the [Xbox] E3 presentation, in the trailer, the fox yawns upon waking up and I was like, ‘Andrew, we need to make a sound for the yawn?’ [laughs] The only vocalization in the game is this yawn — so silly!

But absolutely — audio cues are a big part of everything. We want to make sure that players are rewarded for that poking around and part of that is the sound, certainly. If they bomb a wall, we want that classic Zelda [sings the iconic “Zelda secret sound”] when it happens. And they might be tantalized, like Andrew says, to explore further. So in general, having each area of the world kind of act as a character unto itself. Where you walk into a new area, and there’s new music — Terrence Lee and Janice Kwan, the composers, were very receptive to an early idea of ‘let’s have a lot of music and maybe make them shorter sometimes.’

We can judge how long a player will probably be in this area and we won’t make a five-minute amazing, elaborate, evolving track; we’ll make like a 20-second track because we’re gonna be here briefly and walk out of the room again. But this room will be kind of its own little character when [the player will] walk in, and the fact that this keeps happening — I don’t know if it’s something that players would acknowledge actively, like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna walk in this next room, there’s new music.’ But because you have this kind of ongoing story being told, and you’re being introduced to these new characters and different scenes and rooms that you’re going into, I think it just implicitly invites the player to explore further. So I’m really happy with where it ended up as part of the soundtrack as long it’s a lot of music that stood together. And I’m very happy with how it feels to travel the world and discover all these areas.

Q: I was reading a CBC piece about the Nova Scotian game development scene, and you were the focal point. That speaks to the higher-profile nature of you and Tunic, and it’s also cool to see since it’s usually Quebec or Ontario that gets most of the recognition. Other provinces don’t always get some of that attention. For you, what’s it been like for you to be the sort flag bearer for the Nova Scotia game development scene and get that larger, even international recognition?

Shouldice: I don’t know, I’m just a guy! [laughs] This just happens to be where I grew up and live. I don’t know. It’s very cool. I don’t think that this project would be where it is if it wasn’t for the sort of community of people that exist — not just in Halifax, but across the world — of indie developers being willing to help one another. And there’s a certain amount of privilege that’s required to be able to travel to events and the like, which is a complication now, obviously. But if you can do that, then there are people there that are willing to help and willing to introduce you to folks, and I feel very fortunate to have been able to do that.

Q: Looking back on everything, what were some of the big lessons you took away from making Tunic?

Shouldice: Ah, good question. People often say after one project, ‘I really want to work on something small.’ And I really want to work on something small now, I think. But we’ll see. I think the thing that I am still digesting and understanding and have come to understand a little bit better over the years is where my weaknesses lie and where it’s important to get help with things, whether it be audio and music or business development and that sort of thing. But yeah — understanding what I can and can’t do and how important it is to work with other folks.

Regamey: I think it was a bit of an experiment with this game for me, personally. People will often say, ‘Well, how deep does the rabbit hole go for this project?’ It seems like every corner you poke into, there’s something there waiting for you. And one of my favourite things in games is when you do something that you thought was perhaps not predicted by the developers — some edge case thing you’re doing, but the game responds. There’s something there — ‘we see you, player; we see what you’re doing there.’ And that feels really special. It’s a really special part of interactive media in general.

And the thing about me is I love putting obscure stuff in games for people to find — like that one percent of players. And I have gone so obscure, because again, back to ‘is this possible in the indie game scene, because indie games, etc.’ But yeah, you can do weird stuff in indie games, because there’s no boardroom of people who are saying, ‘this is our bottom line, etc.’ You can just do whatever you want to put the game.

The thing is, though, when you’re doing obscure secrets, we’ve said in past interviews that perhaps there are things we want 90 percent of players to see or 10 percent or 50 percent or whatever that number is, we’ll try to like move the ‘How Obscure We’re Making This Scale’ to suit. And there are secrets in Tunic that the vast majority of players will never see. And that’s totally fine. But oh, man, there are things that I thought were maybe too obscure that were found on like day five. [laughs] So I keep recalibrating how obscure I think I can make something without being too obscure, and I just keep being wrong. It’s just wrong. [laughs] So I feel that next project — perhaps that very small project, Andrew — we can go ridiculous on it and just see what happens.

Shouldice: [laughs] Yeah, that’s another good takeaway — the community of people that have played this. I mean, it’s day one on Xbox Game Pass, meaning there are just millions of people who are able to play this thing. And the realization, the takeaway, for me — or one of them — is that even though you think your weird, niche game about not telling you what to do and having secret languages and that sort of thing is something that people are interested in. There are people out there that love that sort of thing just as much as we do!

This interview was edited for language and clarity.

Tunic is now available on Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S, PC and Mac. The game is also available on Xbox Game Pass for consoles.

Image credit: Andrew Shouldice/Finji

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.