The router market hasn’t changed all that much in the past few years. Standards like high-speed 802.11ac have made things faster, and boxes with myriad antennas have somewhat improved in-home coverage, but the router as an idea — the thing that connects your internet to all the thingies in your home — has not evolved.

Well, scratch that. It has evolved, but to something else entirely. In Canada, most telecom providers, such as Rogers, Bell, Telus, Shaw, Cogeco and many others that own the actual pipe between your home and their central depots, have attempted to make it more difficult to interfere with their hardware. That’s because the modems they rent you to connect to the internet are, in the purported name of simplicity, also routers.

But those routers are usually terrible demon boxes that need to be reset every couple of days. And the software they run, at vexingly impenetrable local addresses like 192.168.1.1, username cusadmin, password k3k5b94naa83n303, are not exactly user friendly. Hell, there’s likely a reason the modem/router in my apartment is made by a company called Hitron, because I’ve nearly hit that thing so many damn times it shuts off in self defence whenever I approach.

Thankfully, Rogers does allow you to turn off the Gateway (read: router) functionality of its modems, as do all other combo network boxes sold or rented by telecoms, turning them into dumb pipes to which you can attach a real gateway, with actual user-friendly software.

But for whatever reason, any dedicated router, be it from Linksys, D-Link, Netgear, TP-Link, Asus, or any other company, has just not worked right with my Hitron modem. After a day or so, I’ll need to reset both units — one at a time: modem first, then router, or heaven forbid the router is issued a local IP address and then you have to do it all over again — to regain the speed I coveted for a few hours when the reboot was fresh, and so the cycle would continue.

Until now.

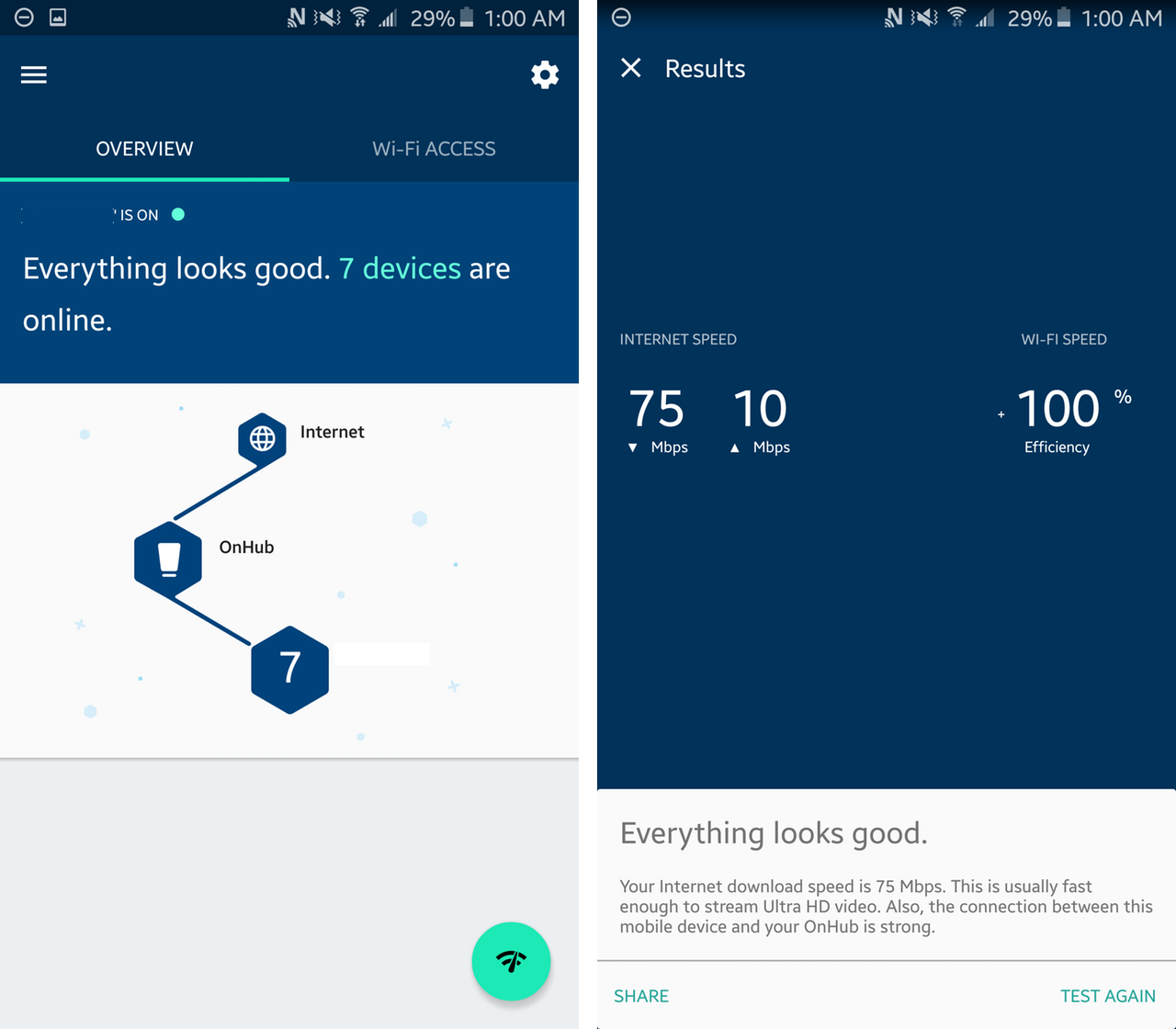

I don’t know what kind of heavenly magic powder Google has worked with TP-Link, its partner in the first On-branded hardware venture, to place inside the OnHub router, but it just works. I’ve been using it, connected to that damned Hitron router, for just over two weeks now, and I haven’t needed to reset it once. Not only that, but every time I run a speed test, be it at 3am or 9am, I report nearly maximum speeds of 75 megabits down and 10 megabits up — the speeds Rogers guarantees I will receive every month.

But let’s back up for a moment. The OnHub is not just a router: it’s Google’s self-branded Trojan Horse into the smart home space, and one that the company says is the first of many On-branded devices to be released over the next few years. At this point, the OnHub itself isn’t much more than a bare-bones gateway, which is why, performance and stability aside, I can’t really recommend it to any but the earliest of early adopters. But wait a year, or even six months, and this thing could be the key to solving your home’s “smart” problem.

Measuring around 19 centimetres tall and 11 centimetres wide, the cylinder tapers towards the bottom, with a plastic facade that can be removed to access the WAN, USB, power and, unfortunately, single LAN port. The OnHub, as I quickly discovered, isn’t a router for the wired generation, so you’ll need a switch to connect all your legacy devices.

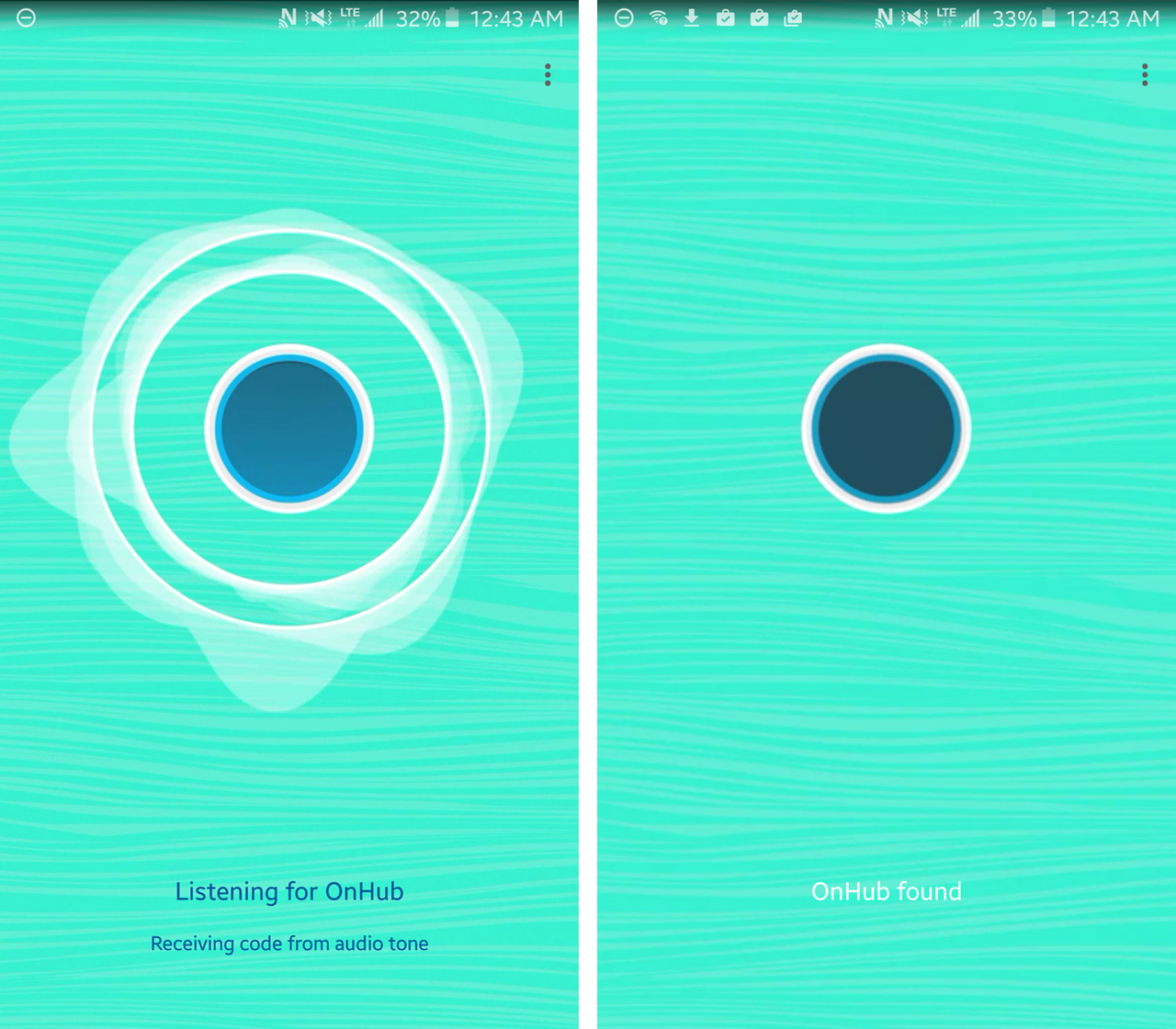

Setup was relatively painless, consisting of an iOS or Android app and a series of musical beats that match the phone to the automatically-generated wireless network. A circular LED flashes a variety of colours, which are ironically detailed on a piece of paper inside the box, indicating the router’s status: green for all good; red for set up problems.

The app is simplistic to a fault, and it is the only way to access the router’s various features. While it was to some extent a relief to avoid the terrible browser-based interfaces of browsers of yore, completely lacking such an option is short-sighted, and likely to be amended in a future release. Companies like Linksys, which provide both user-friendly web interfaces, mobile apps and advanced controls to those who want it, provide the best of both worlds.

The Advanced Networking features of the On app consist of DNS settings — Google’s or your ISP’s — or setting a DHCP server over a Static IP. Port Forwarding settings are available, too, for those who want to ensure services like Plex function without issue.

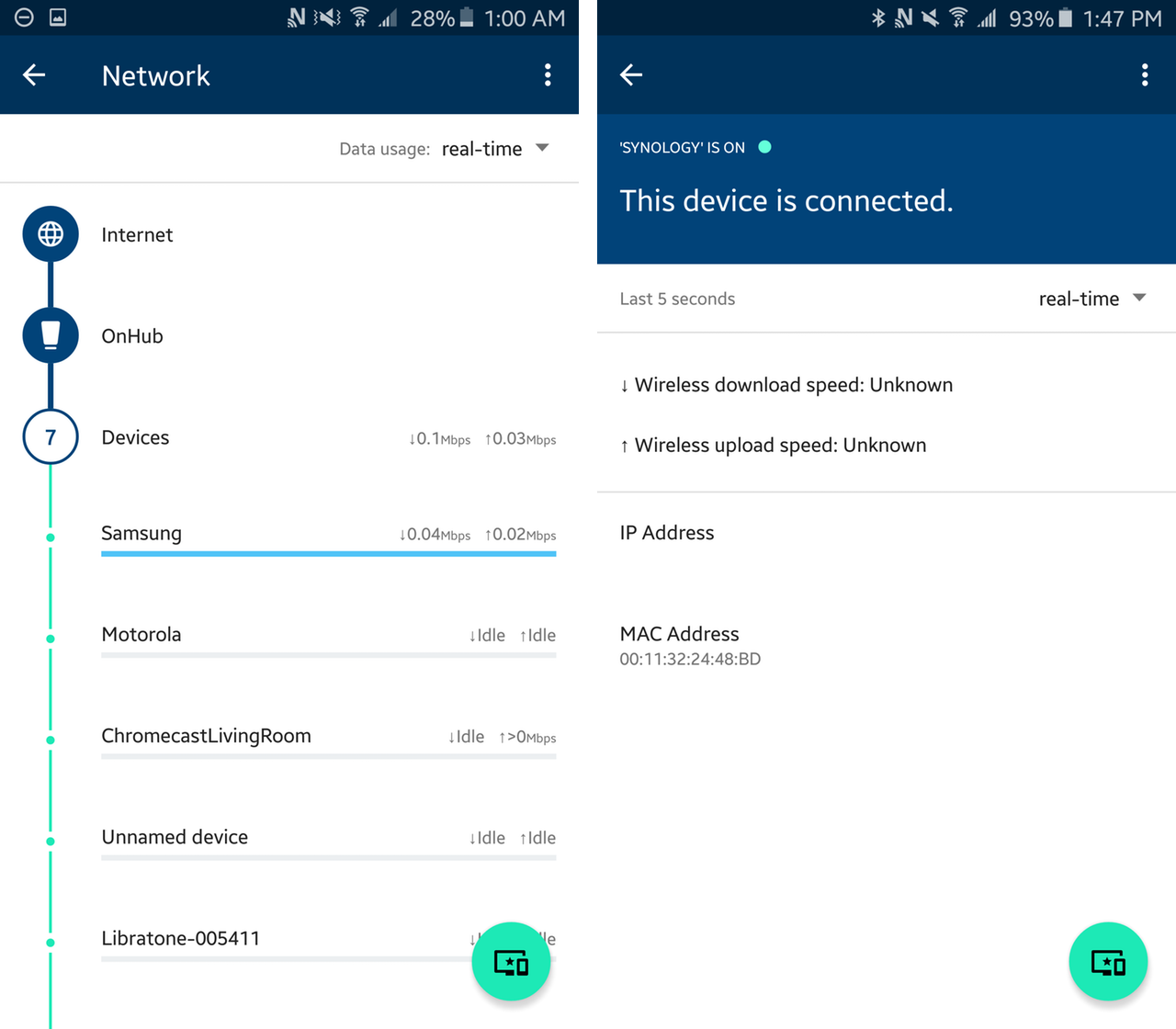

I did experience a problem with my Synology NAS, which was plugged into the sole LAN port of the OnHub for my testing period. While the router detected that the NAS was connected to the internet, it would be display its IP address, which at first prevented me from accessing the device through its web interface. The solution was simple — issuing it a static IP — but it was nonetheless frustrating to have to go through the process.

That said, the mobile apps are attractive and functional, built to Google’s Material Design specifications. What you need to know is the first thing you see: that the router is connected to the internet, and that all the devices connected to the router have an IP address and ample throughput. Google’s goal for the product is to self-regulate: you shouldn’t ever have to access the On app unless something goes wrong, or you want to share access with a visitor.

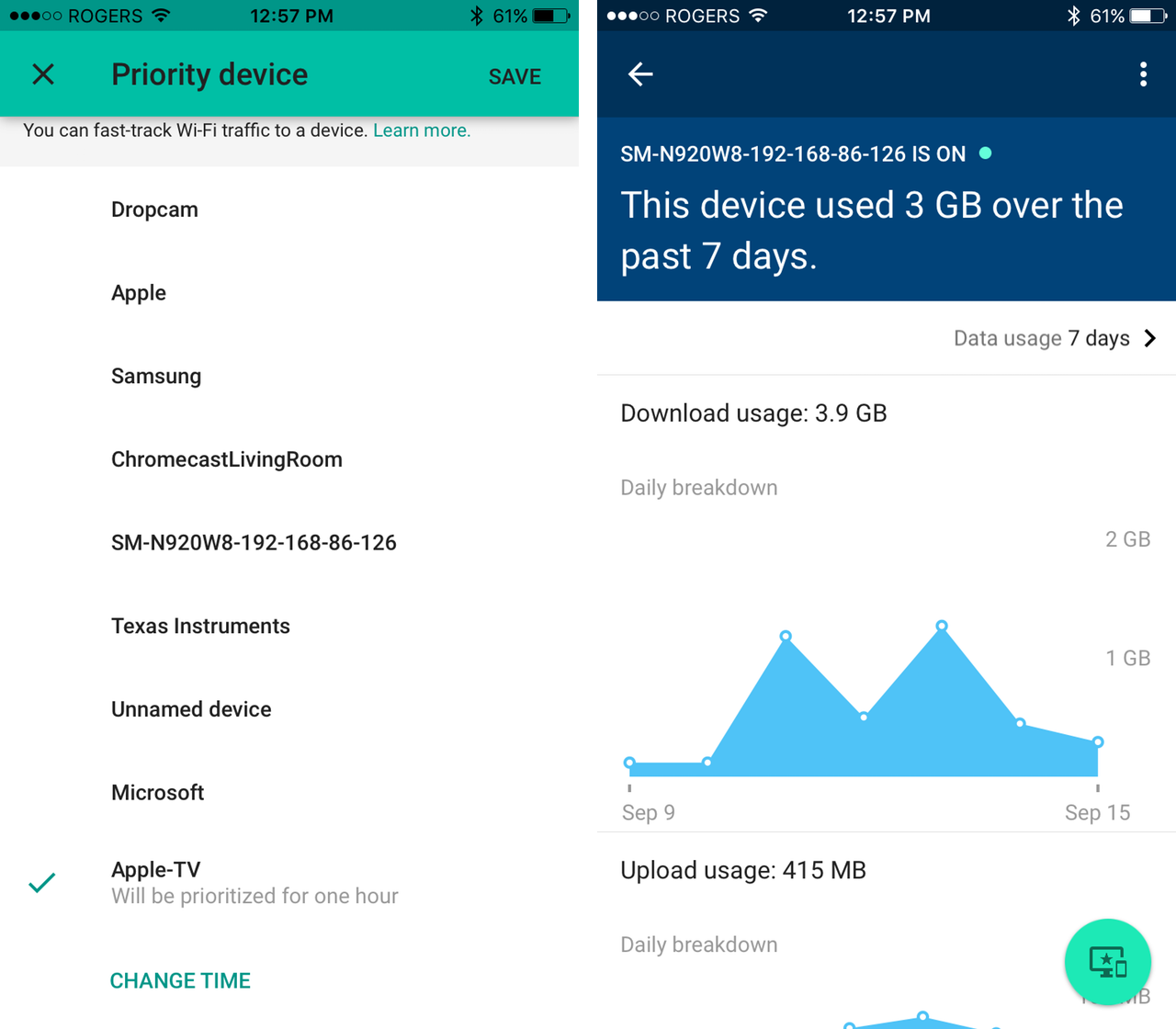

What is really useful is the ability to set bandwidth priority to a particular device on your network for a period of time. With one click you can make sure that Game of Thrones streaming through your Apple TV or Xbox One will not be disturbed in case your smartphone decides to automatically download a huge update in the background. It’s also really helpful to see usage per device in real time, or over three days, seven days or 30 days.

To that end, Google has implemented a number of future-proofing scenarios into the OnHub’s firmware. The router engages in auto-updating directly from Google, which admittedly got my privacy hairs all a-tingle, but the company had laid bare its privacy and data sharing policy to allay those concerns. “The Google On app and your OnHub do not track the websites you visit or collect the content of any traffic on your network,” it says, admitting that it does track what types of devices are connected, and how often a customer opens the OnHub app.

The privacy implications of a company like Google controlling the very conduit by which people connect to the internet is not insignificant, but it’s also overblown. The OnHub is not a modem, so it cannot influence the speed or type of service you receive from your ISP, and it doesn’t set the policies around what kinds of websites you can visit or how you are tracked on the internet. Google’s ad business does enough of that anyway, but don’t expect the OnHub to alter the way the internet works. Except for one main area.

Google automatically overrides your ISP’s default DNS (domain name system) server in favour of its own. You may have at one point or another been told by family or friends to change to 8.8.8.8 or 8.8.4.4, Google’s two connection points for domain name resolution. If a website changes its service provider, or is for whatever reason issued a new IP address, DNS servers the world over receive that new information and propagate the appropriate web address. Occasionally, though, DNS servers are influential in pulling traffic away from illegal or, in certain countries, anti-government web pages.

Earlier this year, for example, the Quebec government decided to use DNS blocking to prevent citizens from visiting out-of-province gambling webpages. It’s unclear what role Google has to play in influencing what websites one can and cannot visit — from what I understand, the company complies with government requests in specific jurisdictions but prioritizes speed above all else — but switching back to your ISP’s (likely slower and less complete) DNS server is a simple toggle in the On app.

As for performance, the OnHub is merely average. But its coverage is excellent, thanks to 13 antennas covering both the 2.4Ghz and 5Ghz ranges, plus a congestion-sensing antenna to quickly change channels when speeds are low. Though my Toronto apartment is relatively small, I was able to obtain nearly the same internal speeds across the apartment, through a brick wall, as standing next to the router itself.

When I say performance, I’m talking about internal networking speeds — the speeds between devices on the network. The OnHub supports 802.11ac, with speeds of up to 1900 megabits over 5Ghz. In reality, those speeds are influenced by a number of factors, the least of which involve the products on the other end. My 2014 MacBook Pro, for instance, has a maximum throughput of 1300 megabits, but it regularly connects to the OnHub at 878 megabits, less than half the router’s theoretical top. And then there’s overhead, which accounts for five to 10 percent of slowdown, plus interference, distance and a whole crop of other factors. OnHub certainly has the technology inside it to be a great performer, but Google is focusing on the experience instead. (Internally, the machine is similar to a smartphone from 2013: it has a dual-core Snapdragon S4 Pro chip, 1GB of RAM and 4GB of storage, which is far more than any boring router requires to function normally.)

The OnHub is more than just a router, as I alluded to earlier. It not only supports ZigBee, a burgeoning low-power wireless standard for smart home devices but Bluetooth 4.0 as well. It also has a USB 3.0 port that, at this time, does nothing. The implications for a router that acts as a hub for all your other products is huge: most ecosystems, from WeMo to Wink to SmartThings require an intermediary to communicate with one’s router, because so few on the market support ZigBee and ZWave, another low-power standard competing with ZigBee. (It’s unclear why OnHub doesn’t support ZWave but, like many standards wars, from Blu-Ray and HD-DVD to PMA and Qi, Google appears to have chosen sides.)

At $269, OnHub is expensive, and right now it’s a shell (pun intended) of what it could be. I spoke to Google’s Melissa Domingues, whose Waterloo-based team designed the OnHub’s mobile app for iOS and Android, who told me that OnHub was built to be perpetually upgraded behind the scenes. Google’s really good at doing this too, at least with its Chrome brand. Think about how many times the Chrome browser, or your Chromebook, has been silently updated behind the scenes, with important new features highlighted only when necessary. She told me that the goal of both the hardware and software team behind OnHub was to make the experience as “magical” as possible. This philosophy applies to any hardware partner Google works with in the future, be it TP-Link, Asus, D-Link, Linksys, or Netgear. Think of the On platform as the Nexus of smart home devices.

The Google OnHub router is available for $269 CAD from Best Buy and is coming soon to the Google Store.

Pros

- Inspired, frictionless set up process

- Nice aesthetics in a small form factor

- Functional, if sparse, mobile apps for iOS and Android

- Automatic upgrades for future-proofing

- Excellent coverage

- Decent performance

- ZigBee and Bluetooth support allow smart home features

- Runs very cool

Cons

- Only one LAN port

- No desktop web access at all

- Barebones functionality as a router

- Lots of features require future update

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.