It’s not uncommon for someone to pursue a second career later in their life, whether it’s because they’re not happy in their current field or simply were inspired to try something different.

For 39-year-old Jaclyn Pope of Oshawa, Ontario, the goal now is to become a full-stack developer to make apps more accessible for the blind and visually impaired. But unlike most people, circumstances completely out of her control led her to this point.

In 2019, after three years of gradual sight loss, Pope was diagnosed as legally blind with all four of the leading causes of blindness in Canada: macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and cataracts.

“When I started losing my sight, I was really, really lost,” says Pope, who had previously been going to school for environmental engineering.

Beyond the general day-to-day challenges that come with vision loss, she says her conditions — which have removed much of her sight — prevent her from properly treating her diabetes. “How do I poke my finger and check my numbers if I can’t see [the insulin pump] and it doesn’t talk to me?” she explains. “How do I check my blood pressure if the blood pressure machine doesn’t talk to me and there’s nobody around to help me? I was a single mom — how am I supposed to do these things?”

As Pope tells it, the medical devices she commonly uses are designed for people with sight. Basic features, such as compatibility with virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, can go a long way towards helping the blind and visually impaired.

“I’ve got doctors yelling at me, ‘do this, do this, do this, do that.’ But none of these things, these medical devices, are actually accessible to me. I still have an endocrinologist who’s going, ‘I don’t think you’re actually giving yourself the right amount of insulin every day.’ Probably not, I can’t see it — I’m doing the best I can!'”

Eventually, the endocrinologist put her in contact with the company that made her insulin pump. When she raised her concerns, she says the company told her it was “not financially feasible” to make its product more accessible in the way she was asking. “That drove me nuts,” she admits.

“And that’s what led me to learn how to read source code — you can read the source code on everything. Even right now, I can just right-click [something], it’ll tell me the source code of what’s going on. And if you can read that stuff, it’s usually a zero or one, a true or false, or a yes or a no. Are you telling me it’s too expensive to get somebody to copy a line of code to make it speak to Apple or Siri or Bixby or Alexa? It’s too expensive? Come on — that’s absolutely ridiculous.”

From there, Pope decided enough was enough. As companies fail to become more accessible, she was going to do her part to make it so. Pope has enrolled in the UX/UI Design program at the University of Toronto’s continuing education program for coding.

Harnessing a wearable medical device to achieve her goal

Thankfully, she’s not alone in her pursuit. Through the Canadian National Institute for Blindness’ (CNIB) scholarship program, Pope has been awarded the eSight 4, a wearable medical device developed by Toronto-based eSight. The organization was founded in 2006 by Canadian electrical engineer Conrad Lewis, who wanted to develop technologies that could aid his two legally blind sisters.

In practice, the eSight is a cutting-edge camera that leverages high-resolution screens and algorithms to provide increased visual information to the brain.

“The device that we have now is really suited for today’s environment, especially for people who are tech-savvy, like Jaclyn,” says Youval Zilberberg, eSight’s manager of client success and customer relationship management. “A lot of people use their iPhones and our device is a connected device, so you’re able to see what’s going on in the eSight. So you can actually share the image that is on the screen on an iPhone, or vice versa — you can see what’s on your iPhone in the screens of the eSight device.”

“For those of us [who grew] up playing video games and had the map in the top left corner, it’s kind of like wearing the eSight device when you don’t have it all the way down. It’s still sitting there, so it’s like that little map, but then you can still see the real world right there — it’s the best way I can describe it,” explains Pope with a laugh.

In using the eSight like this, she can have screens from other devices, like a computer or phone, open and ready to use. This is how she’s able to work on coding projects, as well as manage her online business, Sewing in the Dark.

But it’s also made a huge difference in her personal life.

“I think the first time I put it on, I saw my son’s face for the first time in four years. [From] 16 going to 20 — you can imagine there was quite a difference. And I cried,” she says. “I couldn’t believe my baby had grown. Like, there’s one thing in your mind — he’s growing up, he’s there, and I’d been fighting for so long for everything, for everybody, in the community. I hadn’t realized how much I had actually missed, how much I had lost.”

Pope notes it really became apparent how much she had missed out on when her brother took her to an evening NASCAR race. With the eSight, she could make out so much more of the race than she would have been able to before.

“Previous to that, the best way to explain it was that some of the cars had fluorescent numbers on them, and that’s all I could see. There was no car — it was just fluorescent numbers that were going around,” Pope explains. “When I put the eSight on, it was like the whole picture was painted — I could see everything again. I could even see the sponsors on the board. I could see who was leading in the race. I could pick people out in the stands. I was crying.”

Beyond that, she credits the eSight for allowing her to properly race a car of her own in a video game, go for hikes with her dog Luna, and cook without fear of cutting her hands.

Zilberberg says the device would have also made a big difference in his own life, were it available during his childhood.

“My dad has Stargardt’s [a form of macular degeneration causing central vision loss] — I wish he would have had [the eSight]. Back when I was younger playing hockey, it would have been really great for him to have this device. Because while I remember seeing them there, and it was great to have him at my hockey game supporting me, he wasn’t watching the game, right?” he explains.

“At my older age now, I can kind of give a tip of the hat on that, but now, with the eSight, that’s something that would have changed it for him. He would have been able to watch the game, be closer to what was going on at that time. But unfortunately, [we] had to miss that.”

Making technology more accessible

Image credit: Shutterstock

Beyond medical devices like her insulin pump lacking voice assistant functionality, Pope identifies several other common shortcomings of modern apps that she’d like to fix.

Firstly, she notes that the Worldwide Web Consortium (W3C), the group that develops international standards for the web, needs to expand its guidelines.

“The W3C guidelines are only for websites and browsers. There are no guidelines for mobile apps — period,” she says. “So that’s the number one thing that needs to be fixed. You know, if we’re going to create something, why don’t we have some guidelines?”

She says doing this would help prevent situations where “band-aids, on top of band-aids, on top of band-aids, on top of band-aids” are being put onto apps because accessibility wasn’t considered from the start.

“If everything starts from HTML/CSS, why wouldn’t you make it accessible right from the beginning and make it responsive right from the beginning, instead of adding in all these flashing doodads?” she says.

“I’m tired of going into apps from the navigation bar, just because [on] my Apple phone, I’ve set the text so it’s bigger, so when the text messages come in from my kids, I can read them. Now the navigation bar on the bottom of that app no longer lines up with the buttons. So the button is way over ‘here when navigation is way down ‘here.’ That shouldn’t happen just because I wanted to increase the size of my font within my actual phone. So these are the little things that just should not be happening.”

Pope says this lack of accessibility extends to the technology that is found in schools.

“Four schools have told me they cannot meet my accommodation requests, with the fourth school following up [to say] they wouldn’t even know how to deal with somebody who was blind,” she says.

“I’m just trying to do coding, and I didn’t realize that that was such a barrier. It’s in front of me; it’s words I can learn on my own. I have been learning on my own and I’m trying to get a teacher to teach me, but I can’t seem to get an administrator to say, ‘yes, let her into the school.’ I’ve had full funding opportunities four times, and four times schools have blocked me — I’ve had to turn down those funding opportunities for school.”

She says that even though she has technical skills, schools will regularly not recognize them.

“I have these schools blocking me for these pieces of paper of certification that says, ‘yes, you can do these skills, same as a carpenter, or somebody who went to learn how to make furnaces or whatever else.’ But because I can’t get that piece of paper that says I know Java or HTML or Python or whatever, I can’t get my pay rate to get off of ODSP [Ontario Disability Support Program]. Apparently, it’s politically correct to tell me to ‘go sit in the dark,’ and I don’t think that’s right — I think that’s really, really wrong.”

Fighting misconceptions

In addition to inaccessible technologies, Pope says there’s a general misunderstanding of blindness and the obstacles that those with vision loss typically encounter.

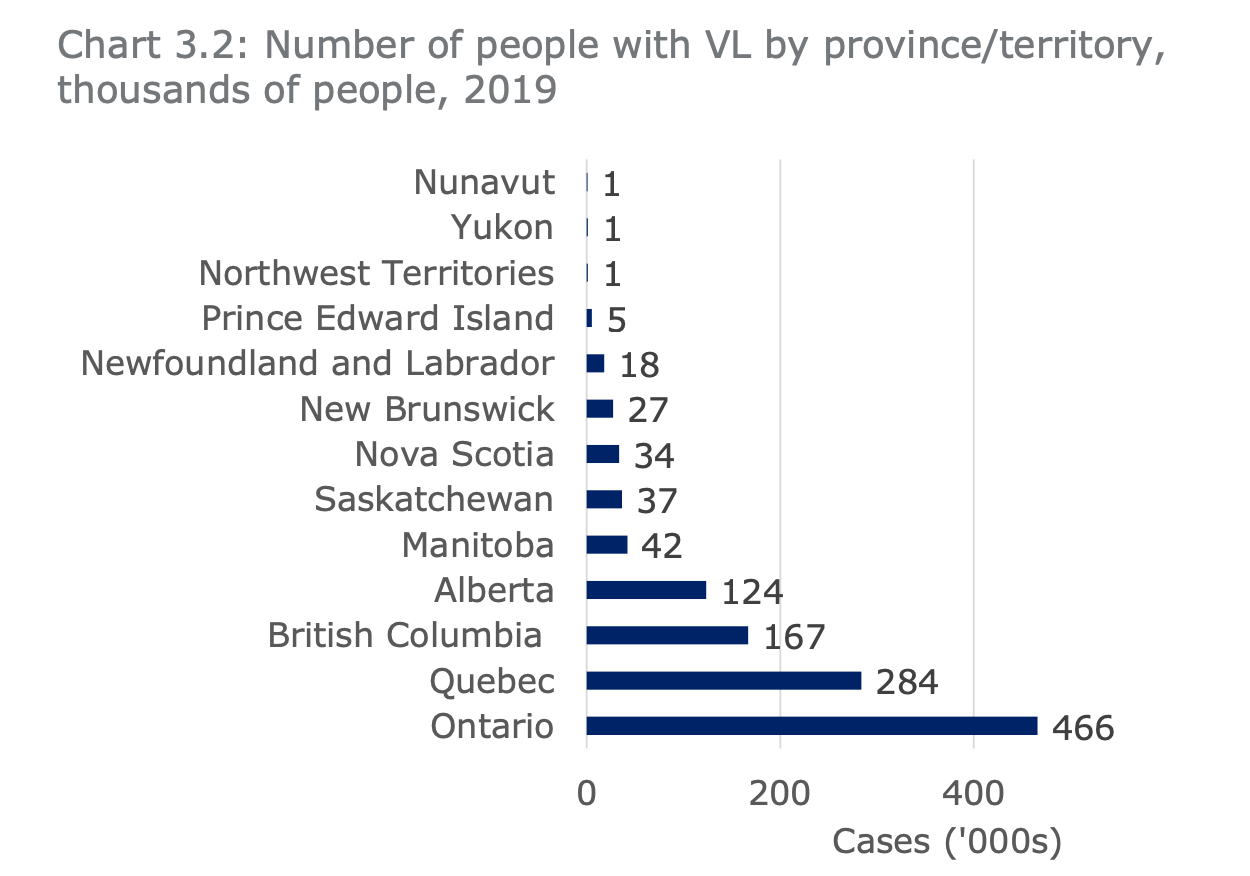

According to the Canadian Council of the Blind (CCB), an estimated 1.5 million Canadians identify themselves as having any kind of sight loss, with 5.59 million others carrying an eye disease that could impair vision.

That said, the ways in which vision loss can manifest can vary. Per the CNIB, a common misconception is that people who are blind have no sight whatsoever. However, the institute notes that blindness comes in many forms; people may experience anything from high light sensitivity and reduced depth perception to blind spots or minimal peripheral vision.

Pope says she regularly encounters those who don’t understand her needs — or, often, even try to. “People assume I’m completely blind, but I’m not completely blind,” she says. “I have little spots, I call them HD spots. And I look through them because I have so many different diseases, so I’m losing my vision in so many different ways.”

She says people often imagine a blind person to look a certain way when that’s not always the case.

“If I’m in a store and I wear regular glasses, I’m told that I don’t look blind. But what does that look like? That’s what I want to know. I can put my regular glasses on now — they’ll look perfectly fine and nobody says anything to me,” she says. “But if I have Luna with me, all of a sudden I’m told, ‘are you training that dog?’ ‘No, I’m not training that dog — she’s there to help me.’ It gets frustrating.”

When the pandemic hit, the employment support group Make A Change Canada gave Pope a grant to turn her office into a fully accessible space. When she went to a Staples to purchase supplies, the store manager yelled at her for not adhering to the markers on the ground to stay six feet apart. Pope, of course, couldn’t properly see them, but she says the manager didn’t believe her, even though she had her black glasses and guide dog. When she sought out another employee, she says she faced even more resistance.

“I remember asking for help, and the person who came over was too afraid to even speak to me. It was almost like I made them sick or something.” A similar situation has happened at a Supercentre location when she asked an associate to get her a smaller cart since the big ones scare Luna. “The guy looks at me as if something’s wrong with me and tells me ‘no, I can’t do that.’ But you’re the actual cart handler, dude — why can’t you do that? Why can’t you understand a small cart, just that one little thing, would make my life easier?”

Shannon Simpson, CNIB’s director of marketing and communications, adds that corporations often have their own misconceptions about disabilities.

“[They often think] creating an accessible workplace is costly — it isn’t,” she explains. As the CNIB notes, some simple ways businesses can become more accessible are by offering software programs that read information aloud, providing screen magnifiers to more prominently display text, keeping common spaces like hallways obstacle-free, or even adding lighting into a room.

“If you are not using these technologies, how can you implement them and use them, if you have no idea what it’s like?”

To help with this, Simpson says companies should look to the Accessible Canada Act, which was introduced at the federal level in June 2019 to make Canada barrier-free by 2040.

“While society continues to create barriers to inclusion for people who are blind or partially sighted, there has never been a better opportunity for government or corporations to further improve accessibility for people with disabilities,” she says. “This framework is a great place for provincial governments, without accessibility legislation, to start developing their own.”

But Pope says the easiest way to do this is to regularly consult and involve members of the accessibility community.

“If you are not using these technologies, how can you implement them and use them, if you have no idea what it’s like?” she says. “So why wouldn’t you speak to the community? Why wouldn’t you put money into the community, when we’re the ones who are using these devices and accessible technologies all the time?”

Doing so, Pope says, might help prevent old-fashioned hiring practices that make it difficult for someone who’s blind or visually impaired to get a job, even if they might otherwise be qualified.

“When a community becomes complacent, and they no longer want to try, isn’t that a sign that something is seriously wrong here?”

“If you look at Procter & Gamble, [in] their very first level of hiring, you have to go through a computer-orientated hiring system, and they’ll actually have little aliens flying up in the top-right corner, and you have to count them. How is that fair to somebody who’s visually impaired?” she says. “They might be able to do that job 100 percent, but if they can’t count those stupid aliens, which has nothing to do with their job, why are they being denied? Why are we putting these restrictions in front of people? That’s what makes me so mad.”

She notes these kinds of barriers can feel demoralizing, and she’s even been discouraged by those in the disabled community to pursue coding or other ventures.

“After all of [what I’ve gone through], to be told in my community ‘it’s okay to just sit there and stop trying, what’s the point?’ These are people within the blind community or disabled community,” she explains. ‘Why push yourself even harder?’ ‘Why have the headaches?’ ‘Why have the migraines?’ ‘Why even keep fighting for these things?’ When a community becomes complacent, and they no longer want to try, isn’t that a sign that something is seriously wrong here?”

She says she won’t let any of that deter her.

“I think we’re behind the times and I think people are afraid and I think enough is enough. I have no problem standing up and screaming, ‘hey, let’s go, come on, let’s make a change,’ says Pope. “And I’m just looking for people to back me behind that so that I don’t think I’m crazy. Because when I’m told to sit on the couch and sit in the dark, be quiet, be complacent and sit on the shelf and do nothing, that’s when there’s something wrong. That’s when we should all be standing up.”

More information about blindness and visual impairments can be found on CNIB.ca and Fighting Blindness.ca.

Header image credit: eSight

Correction: 14/12/2021 at 11:43pm ET — This story originally attributed that a “common misconception is that people who are blind have no sight whatsoever” came from the Canadian Council of the Blind (CCB). However, it should say Canadian National Insitute for the Blind (CNIB) — this story has been updated accordingly.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.