Already — through text messages, YouTube videos and targeting voters based on personal data — the next generation of political campaigning has arrived in Canada ahead of the 2019 federal election.

But according to the latest rules from Elections Canada released last week, some of these new campaigning techniques are exempt from registration or regulatory requirements. Experts say that leaves grey areas in the laws surrounding the upcoming national vote. Much of this gap has to do with how political campaigns take advantage of the fact that everyone has a smartphone. It turns out it’s a seismic shift in the electoral playing field.

“When the lawmakers went through to update and modernize the Elections Act, they were working from the base assumption that political advertising, sharing political messages or paying to share those messages still happens in this kind of broadcast model,” said University of Ottawa professor Elizabeth Dubois. Dubois studies the impact social media has on the democratic process.

Dwayne Winseck, professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University, agrees. “[The new regulations are] applying the rules that we’ve had for the last 40, nearly 50 years now, that we’ve had in the broadcast and publishing environment into the online space,” he said.

And as we’re quickly learning, what worked then may not work now.

“We actually know that there are those kind of standard broadcast type approaches that can happen online or offline. And now both online and offline count under our laws. But we also know that there are ways to share political messages and promote them that don’t fit that,” Dubois said.

Online platforms key targets of new rules

The new rules from Elections Canada state that English websites with an audience of at least 3 million unique Canadian viewers will need to record and report all the names of the people who paid for and authorized political ads on their platforms, as well as the related advertising content, and hold it for two years.

“The purpose of the ad registry specifically is to provide more transparency so that people, if they see a political ad on a website or on Facebook, can click on that ad or they could go to the registry and see what is the organization behind that ad,” said Elections Canada spokesperson Natasha Gauthier over the phone to MobileSyrup.

Though the ad registry is not without its own hiccups. Google announced early March that it would not allow political ads on its various platforms, as it said it would be too keep track of the registration requirements. Later, the Minister for Democratic Institutions Karina Gould said she would ask Google to reconsider. Facebook’s system was launched later that month. The federal government previously indicated it wants to have further oversight over social media platforms.

The movement towards more transparency feels like a critical change since the 2019 federal election will be the first nationwide contest for the control of the House of Commons since the 2016 Presidential election in the United States. The effects from the blend of social media and advertising amplification became obvious during that period.

The alleged use of Facebook ads by external forces to spread misinformation and sow divisions is something the federal government sought to proactively avoid. While it did enact rules to limit the influence of foreign actors by updating Canadian Elections Act with the passage of Bill C-76, it’s much harder to put limits on domestic players.

New campaigning styles are already a factor

There are four main categories of political communication exemptions to the registry requirements: text messages and emails, user-generated content posted for free on social media, editorials and news content, as well as content posted on a campaign’s webpage or a free service like YouTube or Facebook Page. The ad registry rules also make no effort to account for the way ads reach people these days: targeting based on personal information collected through a variety of sources.

But it would be short-sighted to say these types of communication won’t be used for political messaging, as it has already started. MobileSyrup reached out to the Office of the Minister of Democratic Institutions for comment about these exemptions. A spokesperson said the interpretation of the legislation was up to Elections Canada.

The Elections Canada website characterizes a political ad as any election-related message with a placement cost during the election period. The exceptions to what is considered an ad is laid out in a 2015 document.

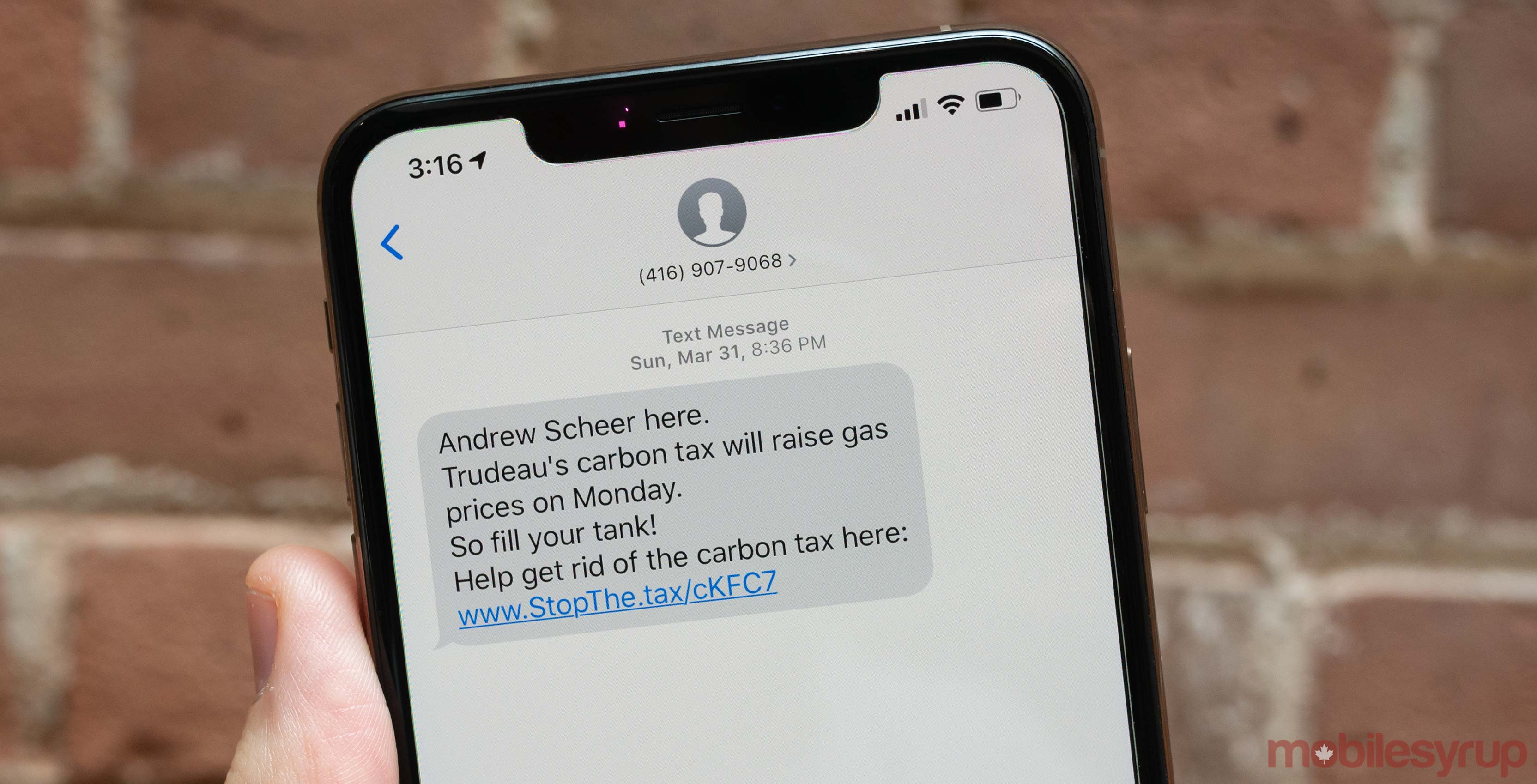

The lead up to the provincial vote in Ontario in June 2018 saw the use of text messages from political parties as well as third-party groups to reach new voters. More recently the federal Conservative party tested out political messages over SMS.

In fact, recent reports from the CBC have the Conservative Party confirming there will be more text message outreach closer to any election. Other experts told the CBC that the other parties aren’t far behind in the use of text messages. Though text messages do not need to be included in the ad registry, parties still need to report any campaign expenses related to disseminating them.

Additionally, the use of free social media services like Facebook Pages and YouTube videos has emerged as an effective way to connect with people. The third-party group Ontario Proud recently registered as Canada Proud to help remove Prime Minister Justin Trudeau from office.

The third-party group follows the mould of right-wing groups from the US, embracing the art of deploying controversial material to get people’s attention. It’s an approach that can pay off with viral dividends on Twitter, YouTube and Facebook. But that’s not what has regulators concerned.

In December 2018, the House of Commons Ethics committee demanded financial information from Ontario Proud. Turns out, the group had been funded through large donations from property developers in the province.

Without a full registry of information, it’s hard to see where this content is coming from and who is paying for it. “It’s really about making sure that we have a good understanding of the campaigning processes that are taking place around elections and making sure that they’re not tainted by corruption. And, you know, big money bags essentially using undisclosed or dark money to influence outcomes,” said Winseck.

“There are some very legitimate reasons why we wouldn’t want user-generated content on social media to be considered political ads,” said Dubois, citing the lower cost threshold for small parties and the similarity of text messaging to door knocking.

Oversight of personal data use by political parties is almost non-existent

The successful election of François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) in Oct. 2018 occurred after the party spent over a million dollars on Coaliste, a platform which targets and identifies potential voters using very specific data points sourced from the already-concerning surveillance economy. Political parties use information collected from their smartphone apps, and companies like the beleaguered AggregateIQ use data to help target political ads to voters on social media platforms.

This isn’t necessarily uncommon as the use of platforms like NationBuilder, which creates databases of voters personal data to help campaigns with getting their message out, grows. In terms of advertising, Facebook has rolled out more transparency for what data may have prompted an ad on your newsfeed.

“It’s down to this idea of the individualization of the political process,” said Winseck. “Campaigning now is not primarily oriented at influencing significant segments of the population and addressing people as members of a population, but increasingly focusing in on individuals as individuals. The smartphone has enabled this highly precise targeting of individuals.”

Not just missing from the Elections Canada rules, personal data collected by political parties ends up almost entirely unregulated. Parties don’t fall under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (though it barely keeps private companies in check). Instead they need to issue a privacy policy under new requirements found in Bill C-76.

“But it’s quite high level there and there isn’t a mandatory format that it needs to look like in terms of how detailed it could or should get,” said Dubois. “There isn’t really recourse for elections Canada or another entity if you are not complying in terms of following through with the statement.”

Because the problem of data is so wide-reaching, it’s hard to assign responsibility for it, says Dubois.

“In the discussions around Bill C-76, there was a bunch of back and forth in terms of should election Canada or should the privacy commissioner be the one dealing with these data issues,” she said.

Minister Gould said the lack of data regulations on political parties is a concern, but has yet to make any changes to the rules after the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada called for more stringent oversight.

Voters need to stay vigilant about what they see and hear online

What can the average person do to navigate this new political environment?

“I think that users need to be aware that there are groups that are trying to influence elections and may be using dubious or unreliable information to do so,” said Jaigris Hodson, who is the program head at and associate professor at Royal Roads University in Victoria, B.C. “It’s important that users understand that social media tends to psychologically work to amplify our differences and divide us.”

Hodson recommends voters seek out information from a diversity of sources, especially outside the internet. “‘Traditional’ Media is subject to libel law so they tend to be a bit more concerned about spreading misinformation,” she said. “That said, they’re not the be all end all. Variety is key.”

Winseck believes that these rules, although firmly in place for the next election, can and should be updated frequently.

“The bottom line here is the integrity of the electoral process, knowing who is spending what in a bid to influence who for what purposes,” he said. “It’s integral to the whole question of democracy and making sure that we don’t have some kind of star chamber-like quality where secret forces are behind the scenes manipulating outcomes in ways that would basically be antithetical to democracy.”