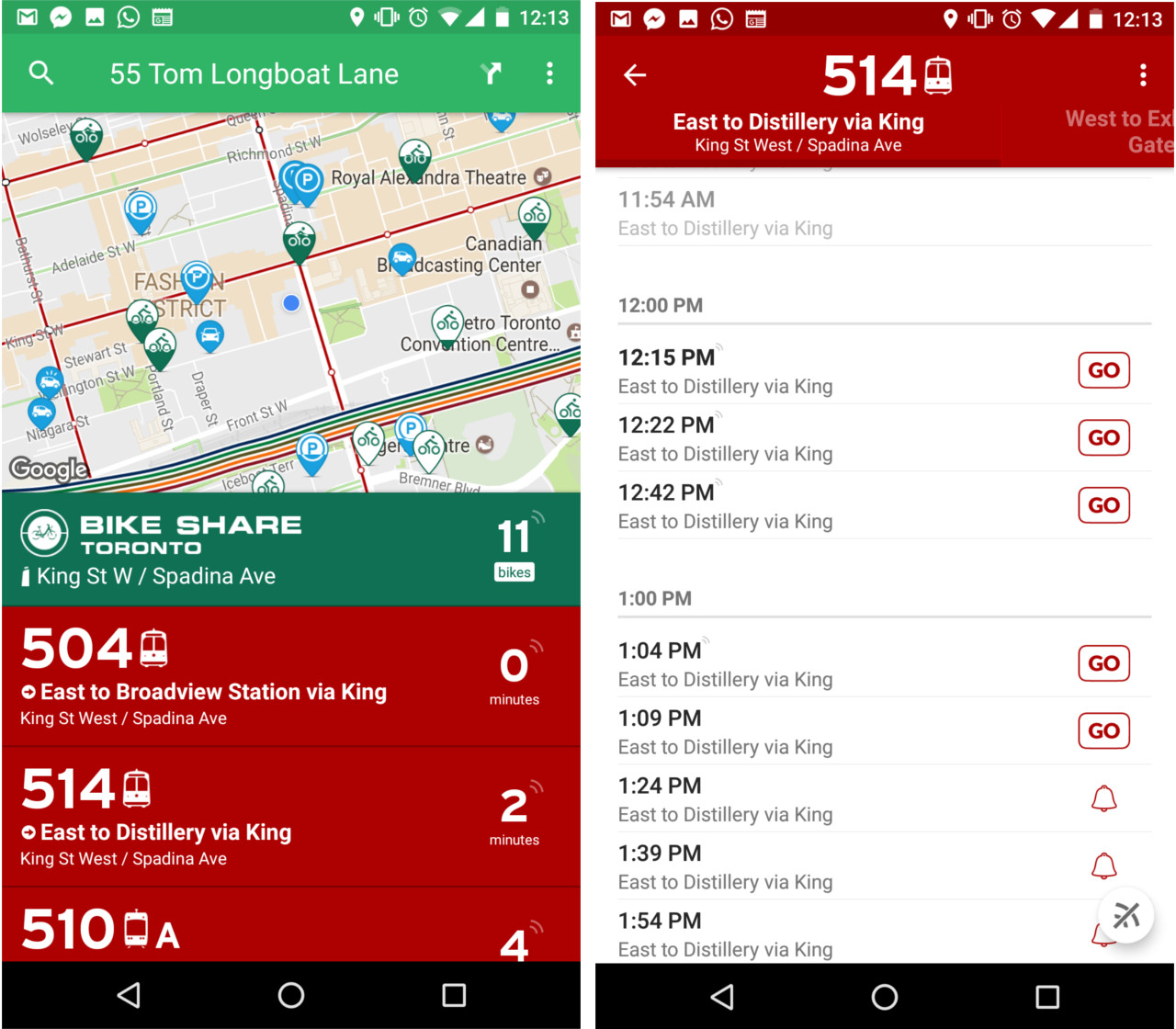

When Montrealers Sam Vermette and Guillaume Campagna were looking to build an app that compiled bus routes and transit times, they decided to go straight to the source: The Montreal Transit Corporation (STM).

Vermette and Campagna didn’t have to set up meetings with the city’s public transit officials — at least, not initially.

Instead, the two developers consulted the City of Montreal’s open data portal and compiled the STM’s publicly accessible data manually.

The openly accessible transit data was enough that Vermette and Campagna were able to build and subsequently release Transit App.

Now, Transit App is available for download on Android and iOS in nine countries, including Canada, the U.S., the UK, Italy and Germany.

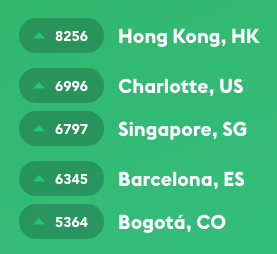

The company is also currently hosting a competition to figure out where the app will launch next.

The top three contenders are Hong Kong, China; Charlotte, U.S.; and Singapore.

While Transit App as a company is now large enough to establish relationships with local public transit partners, much of the app’s data is still compiled by accessing and processing data open data portals around the world.

While Transit App as a company is now large enough to establish relationships with local public transit partners, much of the app’s data is still compiled by accessing and processing data open data portals around the world.

“Even though we get the data…from transit authorities, there’s still a lot of work to be done with it,” explained Jake Sion, Transit App’s COO. “We process it, clean it, reformat it.”

For Transit App’s developers — and for developers building similar apps in the communities where the Transit App is not yet available — open and accessible data is an absolute blessing.

What is ‘Open Data?’

Government websites — for reasons including security and privacy — have never really been “open” or “accessible” in the conventional sense.

For example, you can usually learn more about when an election is set to take place, but it’s quite rare to be able to access individual voter data to figure out how, when, and where citizens cast their ballots.

A curious citizen looking to learn more about their community usually needs to consult a specific government source to access public records, and even then, there still exists the possibility that data is missing, or incomplete, or — worst of all — uncompiled.

As citizens embrace the Age of the Smartphone — and the Age of the Openly Accessible Internet — governments are also entering a new digital age.

Enter the Age of Open Data.

“This is one of the highest levels of engagement you can have in the 21st Century,” said David Rauch, a strategic planner on the City of Edmonton’s open data team.

The Government of Canada’s definition of open data says it all:

“Open Data is defined as structured data that is machine-readable, freely shared, used, and built on without restrictions.”

Simply put, it’s publicly accessible, statistical data, compiled, and curated to reflect almost every conceivable subject that can be classified as a matter of governmental record.

Everything from public transportation to recreational activities to gas line and water main accident rates to the number of trees in specific public spaces in a specific geographical region to the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder rates in veterans can be accessed in some form through an open data portal.

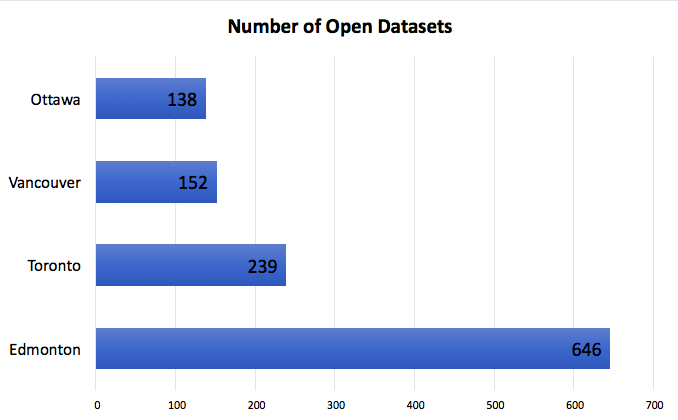

The cities with the greatest number of open datasets are Edmonton, Toronto, Calgary, Montreal, Vancouver, and Ottawa.

Who curates a government’s open data framework?

Make no mistake, open data is openly accessible from any Internet-connected device around the world, but the information contained in each dataset is checked, double-checked, and then triple-checked to make sure that it conforms to municipal, state, and federal privacy and information laws.

For example, the City of Toronto’s open data team employs two different kinds of curators to ensure that data is properly organized and catalogued: Data stewards and data custodians.

Stewards are “responsible for the integrity and quality of the related data,” according to Lan Nguyen, the City of Toronto’s deputy chief information officer.

Data custodians are the ones who gather specific datasets and specific data points, in order to catalogue information as per the suggestions of the stewards.

“The Data Governance Model framework is a comprehensive approach to manage the quality, consistency, security, availability, and accessibility of data across the City of Toronto,” said Nguyen.

Together, the two groups of curators ensure that, for example, a dataset highlighting hockey registrations for children between the ages of eight and 10 does not provide any specific individual information.

And it’s not only because such a dataset would contain information about children.

Even datasets containing adult citizen information need to conform to privacy and information laws.

In Canada, this means that citizen data cannot violate the federal Privacy Act and Access to Information Act, as well as specific provincial privacy and information acts.

“Every dataset goes through a privacy and legal evaluation before it makes its way into open data,” explained Rauch, about the City of Edmonton’s open data releases.

“The question is ‘Do we have legal justification to be able to share this information publicly?’ Every time someone gives information…we have to have their permission.”

In addition to federal, provincial, and municipal laws, open data initiatives have their own best practices.

The Government of Canada, for instance, subscribes to the Sunlight Foundation’s ‘10 Principles for Opening Up Government Information’:

- Completeness

- Primacy

- Timeliness

- Ease of physical and electronic access

- Machine readability

- Non-discrimination

- Use of commonly owned standards

- Licensing

- Permanence

- Usage costs

How do you solve a problem with Open Data?

In many ways, open data is like a compendium of solutions for problems that communities might not have even considered.

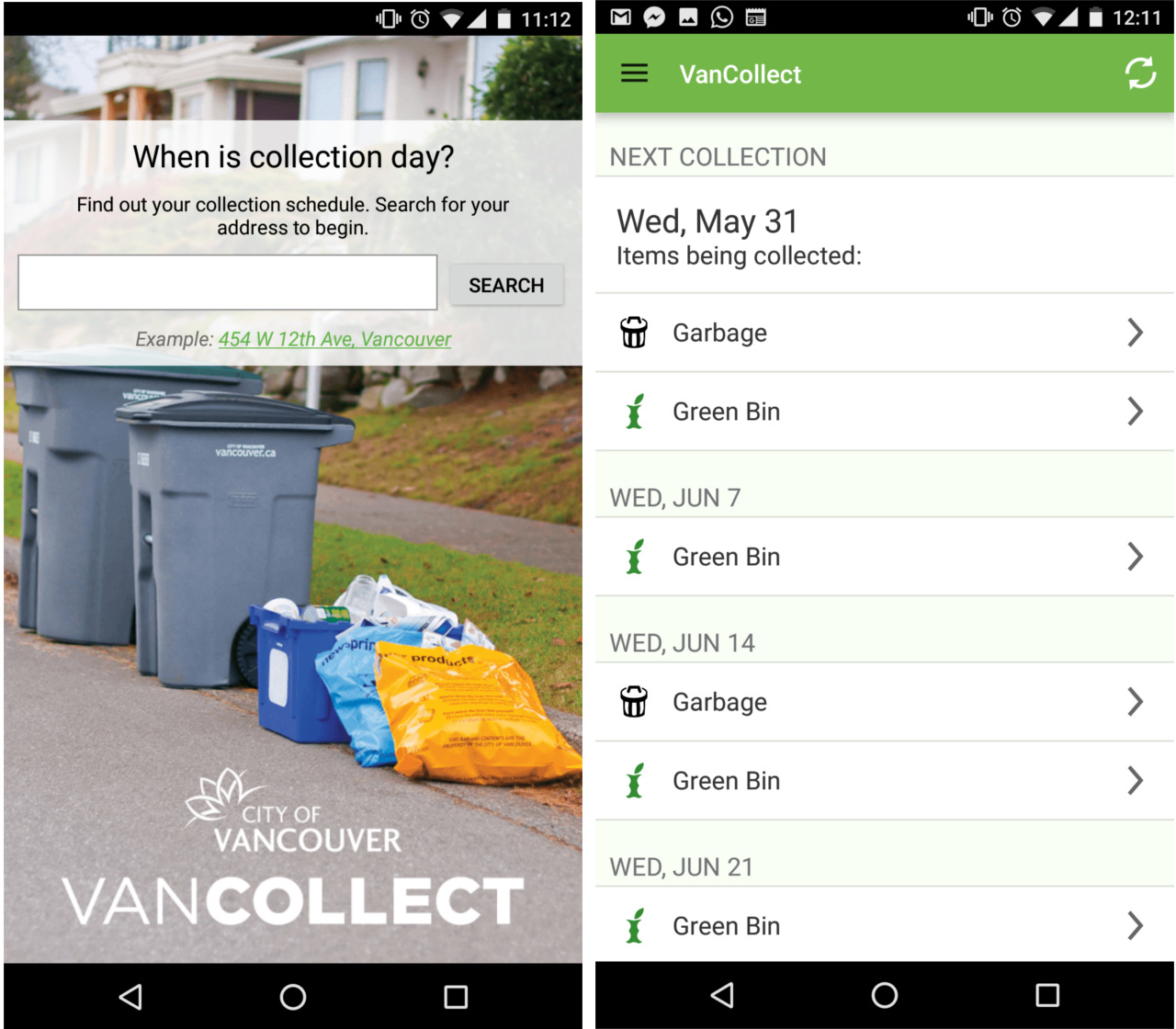

Take VanCollect — the City of Vancouver’s official garbage collection schedule app.

It’s an app that allows users to figure out their neighbourhood’s garbage collection schedules, and it was built using waste data provided by the City of Vancouver’s open data portal.

The company that developed VanCollect — ReCollect — now also licenses the software to the City of Victoria, British Columbia; the City of Kingston, Ontario; Ontario’s Halton Region; and several other communities across Canada.

“From the digital services perspective, there’s unrealized value in the datasets that a city holds,” said Tadhg Healy, the City of Vancouver’s senior manager of digital services.

“We have a huge amount of data and just one single example around our garbage collection data has spawned a very successful digital platform business that has captured markets all around North America.”

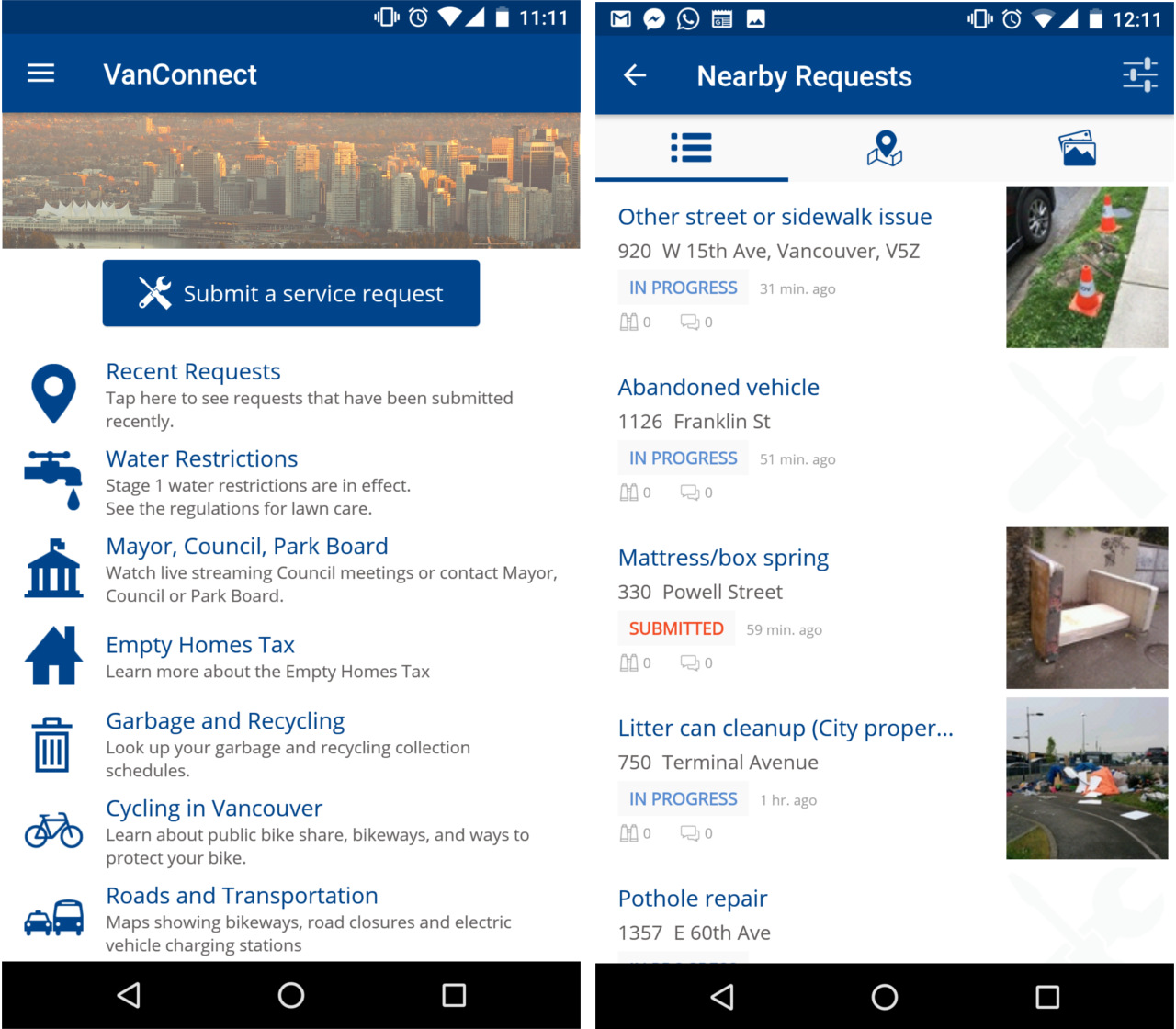

In Vancouver, the City’s open data portal also contributed to the creation of VanConnect — a public services app that allow citizens to submit service requests directly to those best suited to solve the problem.

For governments across the country — including the Government of Canada — open data portals are a way to build actual resources that citizens need and ones that they can actually use.

Looking beyond the valley of the apps

According to Connie McCutcheon — the incoming president of the Municipal Information Systems Association of Canada’s Ontario chapter (MISA) — enabling access to open data puts power and knowledge in the hands of the people who can actually do something with it: Citizens.

“I’d actually say that’s the great thing about [open data]…municipalities tend to gather data for a single purpose, when it can have many purposes when it’s released to the community,” said McCutcheon.

What this means is that datasets pertaining to neighbourhood food prices, career opportunities, and farming can be used by developers who might not have even cared about these subjects until the information became accessible.

For McCutcheon, connecting citizens with their government’s openly accessible data means providing citizens with the opportunity to learn more about their communities.

It’s an optimistic point-of-view, but it’s a view shared by Rauch, Healy, and Nguyen, as well as the City of Ottawa’s Robert Giggey — the program manager for web services.

“The more information the public has, the more knowledgeable they are when it comes to being involved in civic decisions, and helps put everyone on the same page,” said Giggey.

As for McCutcheon, civic engagement is more than just building and marketing apps — it’s about a noble idea of connectivity and collaboration.

“I have never seen collaboration at this level across all levels of governments as we have [seen] with open data, which is absolutely wonderful,” said McCutcheon.

What comes next — the future is in your hands

As an idea, open data is predicated on the two-way interaction between citizens and their governments.

Sure, governments across the country consistently release data about parks, recreational services, and public transit, but in many ways, it’s up to citizens to fill in the remaining blanks.

Open data initiatives, therefore, welcome public input as much as possible. After all, without the public holding its government accountable, there’s no way for the government to bridge the gap.

“The public requests access and wherever possible we want to be able to provide it,” explains Giggey.

Ultimately, the future of open data — should governments continue listening and engaging with citizens — is a continuous stream of information released to a continuously engaged citizenry.

For developers, like those at the Transit App, open data isn’t just a noble idea — it’s a way of life.

“Open data is key for building what we build, but it’s [also] about taking that data, cleaning it, and compressing it — making it look beautiful to the end user and building all the processes to digest this information,” said Transit App’s Jake Sion.

Update: Article updated to reflect that Connie McCutcheon is the incoming MISA Ontario president.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.