As of November 7th, 2017, a mud house in the Kenyan village of Metipso will be the first in the world host to a full-fledged digital broadcast.

Interestingly enough, however, the story of this Kenyan mud house doesn’t begin in Metipso.

Instead, it begins in the Northern Ontario city of Sudbury.

Sudbury: 1988

Ask Toronto-based visual artist Joel Richardson how his career began, and he’ll take you back to a pivotal moment in 1988.

Athletes from around the world had descended upon Sudbury, Ontario, for the bi-annual World Junior Championships in Athletics.

There was a palpable energy in the air, and citizens of different nations interacted with one another in what was — for many of them — the first time that they’d had a chance to meet someone from a different part of the country, let alone a different part of the world.

Richardson, however, doesn’t remember 1988 because of a particular race or athletic event. At 16, his younger self was a “running fan,” but wasn’t actually a competitor.

Instead, 1988 was the year that Richardson met Matthew and Jonah Birir — two Olympic-class athletes from a village in Kenya called Metipso.

The Birir brothers met Richardson through a simple twist of fate. Though they initially had little in common other than their mutual love of sport, the three young men quickly struck up a jovial camaraderie.

“We exchanged addresses and they said you should come train with us in Metipso,” said Richardson, in a phone interview with MobileSyrup. The young Richardson decided to that the opportunity granted to him by the Birir brothers, and traveled the almost 13,000-kilometre-journey to Metipso.

The young Richardson decided to that the opportunity granted to him by the Birir brothers, and traveled the almost 13,000-kilometre-journey to Metipso.

“When I went there, [Matthew’s] family took care of me like I was their own,” said Richardson.

Richardson helped the Birir brothers train for their Olympic debut, living with the family and learning some of the language and the customs of the people of Metipso.

Four-years-later in 1992, Matthew Birir won the Olympic gold medal in the 3,000-metre steeplechase.

Metipso: 28-years-later

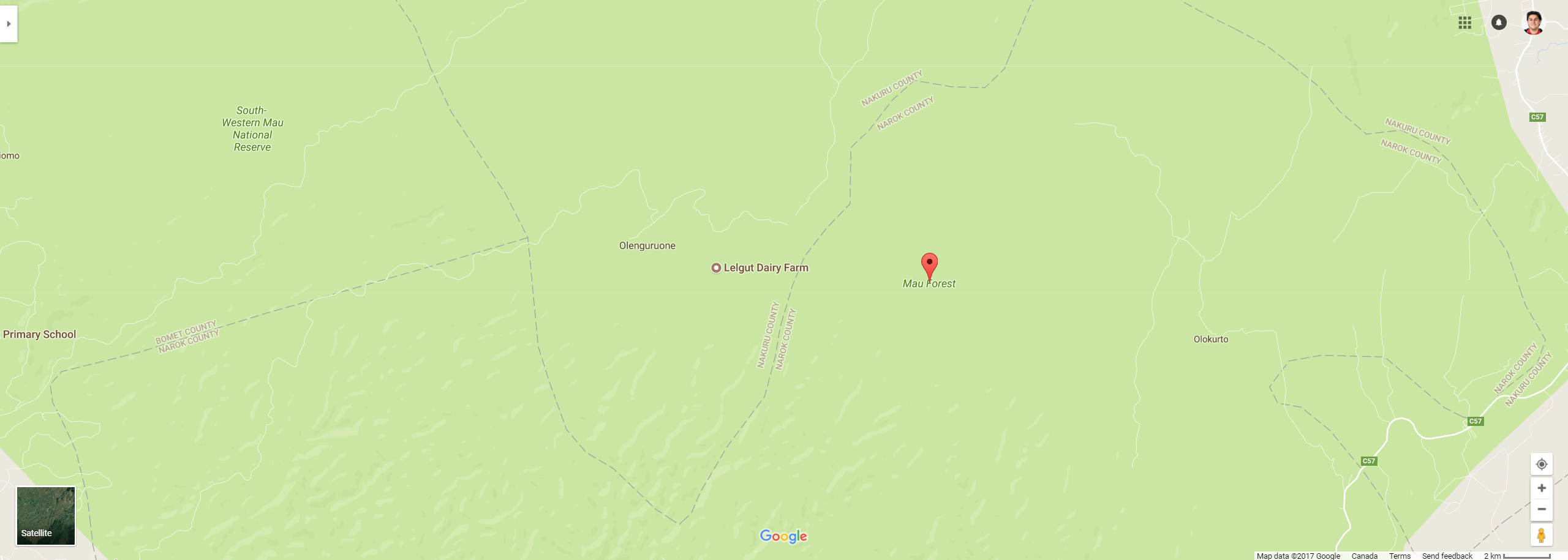

The Mau Forest is a forest complex that rests at the heart of Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, in the western part of the country.

According to the African Wildlife Foundation, the forest “serves as a critical water catchment area for the country,” with many of the rivers flowing through the forest acting as “lifelines for much of western Kenya’s wildlife and people.”

Search for the forest on Google Maps — indeed, look at any map or any photograph of the forest — and you’re greeted by an abundant ocean of green. Within this ocean of green is a bustling forest ecosystem that’s also populated by a number of human settlements.

Approximately 12 kilometres west of the Mau forest is the small village of Metipso.

It’s the home of Matthew Birir and his brother Jonah — who, it should be mentioned, placed first at the 800 metres at the 1988 competition, as well as fifth at the 1,500 metres at the 1992 Summer Olympics — along with their brother Solomon and the rest of their family.

However, the village of Metipso is also home to the Metipso Portal — a radio tower thats broadcast from a traditional Kalenjin mud house. The idea to build the portal emerged in 2016, when Richardson returned to Metipso with his son.

The idea to build the portal emerged in 2016, when Richardson returned to Metipso with his son.

Having spent most of their adult lives apart, Birir and Richardson wanted to find a way to connect Metipso to the rest of the world.

For Richardson, it would be an opportunity to give back to the community that helped shape him during his formative years. For Birir, it would be a chance to give back to the home that so greatly influenced his career.

Most importantly, Richardson and Birir wanted to accomplish their goals without sacrificing the village’s traditions, its language and its Kalenjin culture.

“Part of the charm and the beauty of the village was the traditions and culture.”

Matthew Birir himself is Maasai on his father’s side and Kalenjin on his mother’s side — one of approximately 4.97 million Kalenjin who make up Kenya’s approximately 48.46 million population.

The people in Metipso speak a combination of Kalenjin and the African continent’s lingua franca, Swahili.

So when it came time to decide on the structure through which Metipso would broadcast itself to the world, it only made sense to use a traditional Kalenjin mud house.

“Part of the charm and the beauty of the village was the traditions and culture,” said Richardson. “That’s how we came up with this idea for this traditional Kalenjin mud house.”

Wireless connections don’t come cheap — and neither does broadcasting equipment

A typical Kalenjin mud house is “typically a patched grass roof and there is mud in the floor and the walls,” according to Birir.

“We have to maintain the house, so every now and then some ladies will come and apply fresh dung and mud… [they use] traditional skills to maintain the structure,” said Richardson.

Of course, what makes the Metipso Portal station so distinct from the usual Kalenjin habitats is the noticeable metal telecom tower jutting out of the earthen structure.

This contrast between traditional and contemporary — analogue and digital — lends the Metipso Portal a distinct character that harmoniously blends two very specific forms of technology.

Still, while the cost of maintaining the mud house might be more manageable, the cost of building a radio tower — as well as the cost of cameras, computers and microphones — isn’t something you can just wave away.

To begin with, Birir and Richardson partnered with Kenyan national telecommunications provider Safaricom to establish a microwave antenna that would boost Metipso’s wireless signal.

Then, Matthew financed the construction of the tower out of his own pocket, while he and others from Metipso built the tower themselves. “One day on Facebook, I saw that Matthew was building a tower with no engineers or anything,” said Richardson. “They got the steel [and] they welded it at the village at Matthew’s saw mill.”

“One day on Facebook, I saw that Matthew was building a tower with no engineers or anything,” said Richardson. “They got the steel [and] they welded it at the village at Matthew’s saw mill.”

The Metipso tower’s signal wasn’t initially strong enough to reach a nearby signal tower. So Safaricom installed an additional antenna on the neighbouring tower to boost Metipso’s signal.

Thanks to some extra technical help that Matthew’s brother Solomon has been providing from Kansas, the Metipso Portal has been running relatively smoothly since then.

“They got the steel [and] they welded it at the village at Matthew’s saw mill.”

As for the cost of equipment, Richardson explained that the project has had to start small, relying on support from Richardson himself, as well as friends and family with spare cameras and other equipment.

“So far, it’s all been just personal donations,” said Richardson.

Of course, building a broadcast station was only the first step. Once everything was ready, Birir and Richardson had to figure out what to do with the whole setup.

They decided to launch Metipso TV — a digital media channel hosted on YouTube that would produce content specifically catered to the people of Metipso, as well as the rest of Kenya.

“Metipso TV is just a platform,” said Richardson. “Our goal is to create correspondence in the village that can start telling their own stories.”

Among Metipso TV’s segments is one on fashion, which Richardson is especially excited about.

“Kenyans are very stylish people,” he explained.

Growing pains, but a steady start

Birir and Richardson spoke with MobileSyrup a few days before Kenya’s second 2017 presidential elections, on October 26th.

While there was quite a bit of uncertainty about the country’s future — as well the country’s overall political stability — both Birir and Richardson explained that due to Metipso’s geographic location, the village itself was actually quite safe.

“The political situation is not really stable… the citizens are concerned about this, otherwise it will be okay,” said Birir.

“A big part of what we’re developing is our technology team.”

Ultimately, the elections took place with protests in some of Kenya’s largest and most populous cities, but Metipso was relatively untouched by the furor.

“[We’re] far away from the trouble,” said Birir.

As of right now, Birir and Richardson are working on building up a dedicated team of skilled workers who will be able to operate the station and work out some “bugs with our transmission,” according to Richardson.

“A big part of what we’re developing is our technology team,” said Richardson.

Both Richardson and Birir also believe that setting up a Patreon fund will also allow them to afford better equipment, as well as a dedicated station manager capable of making sure the whole operation runs smoothly.

As one can imagine, Birir and Richardson are nonetheless proud of what they’ve been able to accomplish.

“We’ve been friends for a long time and we have a lot to do for Metipso and my country and also to connect Metipso in terms of technology,” said Birir. “I think there’s a lot we can do.”

It might seem strange, this broadcast station in a mud house. In many ways, however, it’s evidence of the kind of work that can be accomplished from a simple act of human connection.

On it surface, the Metipso Portal is a story about something wonderful achieved by a man from Canada and a man from Kenya. At its core, however, the Metipso Portal is simply one of many stories made possible by the fact that there is no greater accomplishment than one forged from a bond of friendship and familiarity — even if those bonds are forged halfway around the world.

Metipso TV will be broadcasting live from the village of Metipso from November 7th to November 10th, 2017. Each hour-long broadcast will be hosted by Canadian actor Benjamin Blais.

If all goes according to plan, this strange experiment will seem completely ordinary — and that’s what makes it so extraordinary.

Images courtesy of Metipso TV.