In September, Chicago-based Waking Oni Games released Onsen Master, a hot spring customer management simulator.

While the premise and overall aesthetic draw heavily from Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away, the game was developed primarily by Black creators. It’s that intersectionality between Black experiences and Japanese media that Waking Oni’s founder, Derrick Fields, finds so interesting. For the game designer and Northwestern University professor, it’s an opportunity to help further representation in the industry for both BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ communities.

MobileSyrup sat down with Fields to learn more about his work on intersectionality, Black representation in gaming and how we can all help bring more Black creators into the industry.

Question: To start, can you tell me a little about your journey into game dev? What are some of your earliest memories playing games and when did you decide that you wanted to pursue this as a career?

Derrick Fields: My experience in gaming and memories go way back to Sega — like the Sega 16-bit and all of that. But I think where it was really instilled in me was playing the RPGs, mostly from Square Enix, as they arrived on PlayStation. Behind me is a little figure from Final Fantasy IX [a plushie of the Black Mage character, Vivi] and that’s probably the most beloved Square Enix experience that I had growing up and certainly resonated with me. I think it was maybe sometime around then that I continued to be really enamored by JRPGs and understanding that genre, specifically.

But it wasn’t until I was in university that I was pursuing a degree in illustration to go into character design and that sort of thing. But it at one point clicked, and I said, ‘Oh, right, people make video games — all of the stuff that you’ve been enjoying, of course, there’s somebody behind it.’ But I think it really clicked, and I made a decision to pivot into 3D modeling and animation to pursue a creative career in gaming.

Q: You talked about being a fan of JRPGs like Final Fantasy, and I know you’re big into anime, like Spirited Away. And, of course, your game is Onsen Master. What is it about that intersectionality that speaks to you? What is it about the Black experience that meshes with Japanese media and culture?

Fields: I have to announce in this interview that I’m wearing an anime shirt, which was not intended, but it seems to be something splattered across my closet. [laughs]

When it comes to these intersections, this is something that I pursue heavily and a conversation that I pursue heavily. And that realizes itself in a couple of different avenues. I’m a part of the Japanese Arts Foundation here in Chicago, and most recently became the president of that non-profit. And so what we do is create a lot of events based in the community of Chicago that celebrates all the different intersecting cultures that come together to discuss and take joy in participating in Japanese media — games, anime, film. And when it comes to that intersection in Black culture, this is a conversation that I’ve pursued a lot — to the point that we’re at the research paper point in that area of discussion.

Intersections with Black culture and Japanese media have been happening for a while. We see these types of resonance or examples in media such as Cowboy Bebop with the inclusion of jazz [and] more obviously in Samurai Champloo with hip-hop and samurai coming together for its melody. And then, of course, just as prolific with Afro Samurai, really just putting it right in front of you. There’s been a gap since that time and media has still been explored until we came all the way up with Carole & Tuesday, Cannon Busters, and, most recently, Yasuke [a story about a Black samurai], which included LaKeith Stanfield. And so these conversations are happening in media and there’s a clear impact of anime and most likely anime from Toonami era, as most of us grew up with that in high school, and now we’re in the position to be able to create media that is inspired by that.

This doesn’t come without acknowledging the impact of shonen shows like Dragon Ball Z or Naruto on the Black community and how we might code certain characters as Black, even though they might not on the surface represent that. One example is Piccolo [from Dragon Ball Z]. Piccolo is ubiquitous as a Black dad among at least my peers, and certainly those who I interact with online. And then, of course, just the matchup of Naruto and its entire series.

But to get into why that intersection happens and maybe why that has a resonance — I think of it in two different ways. A lot of these shonen shows present a story that characterizes somebody who is coming from nothing but develops their ability or strength or mindset to come up against opposition, and I think that is a goal that is prominent, certainly, within individuals like myself. And then another example that I think maybe helps to characterize this relationship is actually another documentary, Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks. [Editor’s note: while it’s on Netflix in the U.S., it’s only available on PVOD platforms like iTunes and Google Play in Canada.] It’s really great. It establishes the relationship between both Japanese and Chinese martial arts films on the Black community in the Bronx, and how that influenced an entire genre of Blaxploitation films, black stunt artists, and even furthering that in its community. So there’s a lot to be observed, and I really enjoy making a concerted effort to identify this conversation.

Q: When you take on something like Onsen Master, there’s an inherent risk in tackling a culture that isn’t your own. When you go about making a game like that, how do you avoid issues of appropriation and handle that subject matter respectfully and earnestly?

Onsen Master (Image credit: Waking Oni Games)

Fields: Certainly. I think in some of the examples that I shared, that is, in my opinion, one of the better routes to pursue. And that is not to be, say, a Black individual that is making intrinsically Japanese content, but find ways to include Black representation in media that is sort of inspired by it. Onsen Master, yes, does include these fantasy towns on a fantasy island that is very much embedded in Japanese lore with the inclusion of Yokai or Japanese spirits. But where the representation occurs is by including characters of different skin tones and genders within the denizens or characters of this game.

It’s not my goal to, say, tell a specific Japanese story. I think that’s where it starts to tread into the territory of being a little more appropriative, or at least needing to be much more conscientious of it. And so I think of Onsen Master as really the start of that conversation, but ultimately wanting to build more games and more media that lean even further to automate inspired content that is ultimately representative of Black individuals and Black stories. And so, you know, Boondocks and some of the other examples also fall within media that is derived from that same conversation,

Q: Your work with intersectionality is one facet of representation. What are some other good examples of Black representation in games in terms of the characters and stories being told?

Fields: When it comes to Black stories and Black characters, I think one thing that’s important to acknowledge is Black representation in games doesn’t have to always come with the story being intrinsically Black; the inclusion of Black characters without Black stereotypes is an important thing to acknowledge. And so when I think of stories that are successfully doing it, it’s representing not just Black characters, but Black and Brown characters in a normal environment that is reflective of our own realities, diverse communities and spaces. Marvel’s Spider-Man: Miles Morales, of course, I have to champion that one in its representation, feeling so natural for Miles’ life. When he steps outside of his home and you see his interactions in the city, and that being inclusive of both his Black and Latin backgrounds. I think that game is an incredible example of how things can be done successfully.

Marvel’s Spider-Man: Miles Morales (Image credit: PlayStation)

Taking it in a slightly different direction. I love how Deathloop has included, so naturally, two different characters that are just a part of the story, but neither of which are stereotyped as being caricatures of Black culture. And certainly, there are many others. I’m glad I can say that we’re at a point of being able to represent many others. And there are indie developers that are doing a lot of work to create those representations as well and show the diaspora of how many spaces and environments we can take up.

Q: On the flip side, what are some areas of improvement when it comes to the industry’s Black representation? For example, I remember a conversation about Elden Ring‘s limited character customization options for Black hair.

Fields: I’m glad you bring up character creators because it ends up being a space that, from a Black experience, is kind of that first engagement, that first barrier, of ‘can I be represented in this game?’ Elden Ring is a great example. But when it comes to other games, historically… I did sort of laud Square Enix for being a game company that inspired me to jump into games and show me these magical worlds. But the relationship with one of my favourite game companies is somewhat contentious because it wasn’t until later that I started to acknowledge that it wasn’t representing Black individuals as well as other cultures very well. And so that’s an area — and certainly the area of JRPGs — that could do a little bit better.

But I say this with a bit of trepidation because I don’t necessarily put the onus of a Japanese company, with predominantly Japanese studio members, to represent Black culture well. That’s a systemic result of there being no Black individuals within that space to speak to how they could be represented better. And so I would at least say, or nominate the responsibility — if a studio is endeavouring to represent diverse cultures in a game or include those, then certainly consulting with those same groups could be one starting step to representing those spaces. We might have seen better examples of, say, Sazh in Final Fantasy XIII. And, hopefully, arrive at a milestone that studios that are endeavouring to create diverse short stories also reflect that inside their company — that there are diverse team members contributing to those titles so that they can inform much better things like hair texture and skin tone.

Q: On a larger note, there are obviously many Black people who play games, but we don’t see that reflected on the developer side. What are some of the ways the industry can collectively help bring in more Black creators?

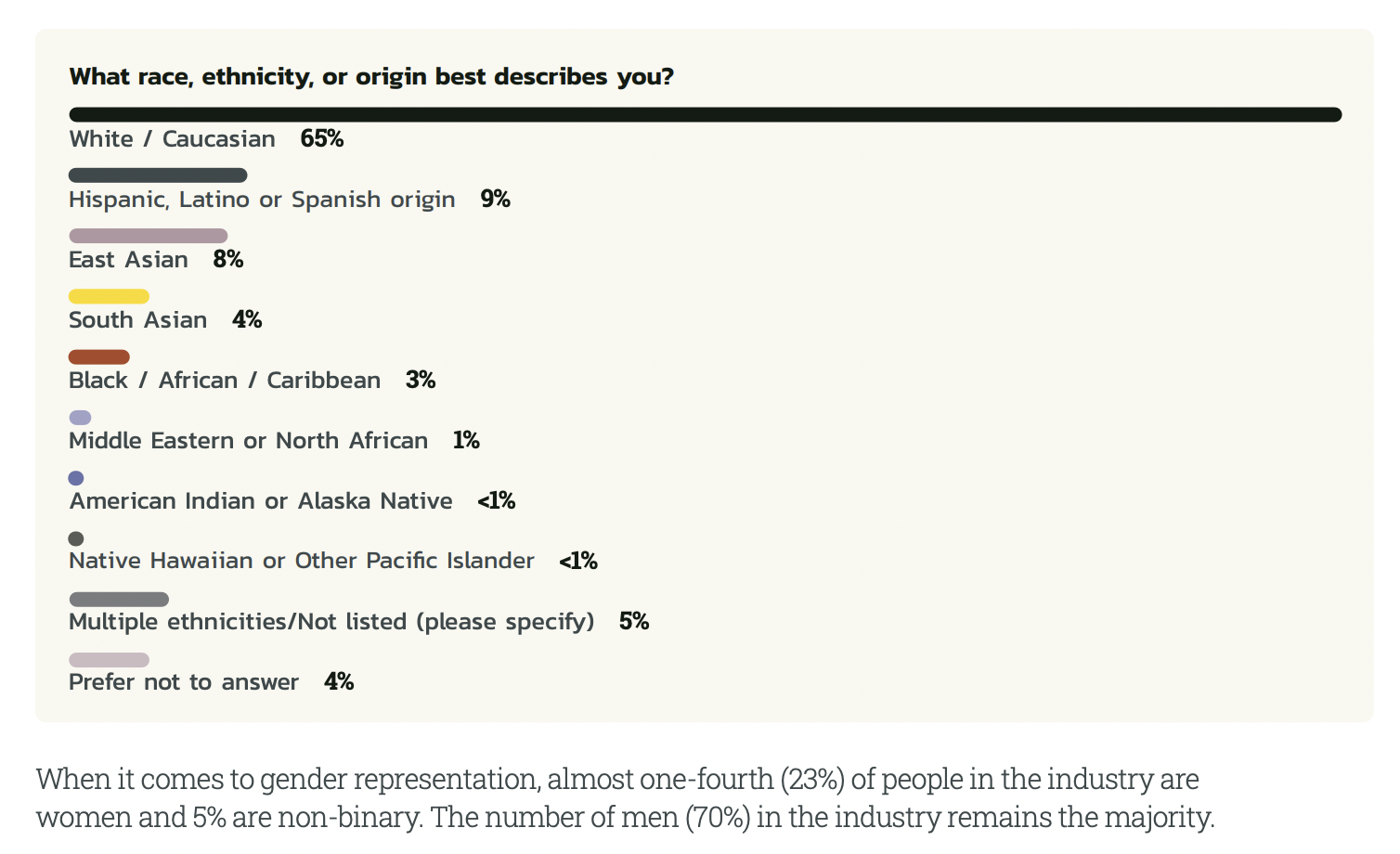

The most recent Game Developers Conference survey shows the lack of diversity across the board | Image credit: GDC

Fields: It’s kind of abysmal. The last International Game Developers Association report said that Black individuals made up about four percent of the industry. And then some other statistics, I’d have to check where it came from, but it was like 0.1 percent or 0.01 percent of the industry is made up of Black executives. And so when it comes to the answer of how can we position more developers in the industry in both of those spaces, studio roles and executive roles? On one end, it certainly comes with funding opportunities. I think publishers, especially in the wake of Black Lives Matter and the murder of George Floyd, came out to say that they wanted to support Black-led teams and studios. I personally am curious — what results of that were rendered, and if there were other developments that come from that? I personally didn’t see a lot of communication then after. And so it does leave me curious. But I think funding is certainly one example.

And then finding ways that we can give more resources into STEM [science, engineering, technology and math], and the accessibility of tech roles on the high school level. Finding ways to include games is a good starting point — to engage students that they can be involved in games as well. For those who are already burgeoning in their careers as developers and indie developers, it goes back to those funding opportunities that I think should be leveraged for smaller teams, and certainly those who are new to the space. As far as executive roles, just flat out hire more Black individuals and put those individuals in leading roles so that they can inform more diverse outcomes.

Q: On a larger level, what are some of the ways that schools and other organizations can help foster an interest in games?

Fields: This is something that my studio and I are trying to tackle, personally. In Chicago, there are not a lot of game studios, but there are a lot of high school programs, especially for students who are coming from underfunded neighborhoods, to be able to engage with the resources that help inform the career opportunities that are available. And so that includes STEM and that includes art. I’m trying to navigate and understand how we can include video games in that conversation, and ultimately develop a studio that can participate with the organizations that are providing those outcomes. And so this is kind of the beginning of that conversation. And I think, in getting an answer, it’s still forming. But for now, I’m very interested in how game studios personally can participate with, say, non-profit organizations that are making that concerted effort to connect with high school students. Because that’s where it begins. Video games are the thing that is most successful [in terms of] being played by students on mobile phones on their consoles all the time. They’re engaging with some sort of content that is derived from that media. And so it would be incredible to be able to see more studios connect with non-profit organizations doing that.

Q: The term “ally” is thrown around a lot. For anyone who isn’t Black and wanted to learn more and show support, what are some suggestions you would give?

Fields: It comes with these types of actions that have been taken, similar to how this conversation came to fruition — being invited to share my experiences to help inform how we can create, other outcomes, other futures. Extending into other spaces… in some ways expressed a little bit of exhaustion at some of the more clear outcomes of, say, just simply inviting those individuals — Black individuals, brown individuals, queer individuals — to the spaces that you’re curious o hearing from them. And so if that’s a game studio who’s saying, ‘how do we become more diverse?’ Well, come on — just hire those individuals or include them in that space. I think it certainly starts there. But again, it doesn’t make true waves, true change, unless some of those individuals are at those executive levels or at those decision-making levels so that they can continue advocating. It doesn’t mean much if, say, you are a publisher or a funding opportunity who wants to support Black-led teams, but there are no Black individuals part of your curatorial team or advisory team to be able to understand and sort of have some of that bias towards the games that you might be curating.

Q: What advice would you give to Black kids who are interested in games and want to break into the industry?

MARK YOUR CALENDARS!!

We are back with another showcase, where we celebrate Black Game Developers and creatives in this space 🤩

Tune in on the 27th of February @ 10am PST ➡ https://t.co/e2zukgrEL5

Watch this space for more exciting announcements 👀#BlackVoicesinGaming pic.twitter.com/KnWZ6FEShQ— Black Voices in Gaming (@BVIGaming) February 16, 2023

Fields: Well, I have to acknowledge a handful of things. This comes down to resources and their accessibility. By asking the question, I wonder if that same high school student would be in a space to bump into this conversation, this interview, or any others that are having those types of outlets that are serving these types of conversations and trying to promote it. But how can we get the information to that student so that maybe, for MobileSyrup, they know that there’s this type of conversation happening. And so it comes down to resources, and kind of that provision of resources, I think of those non-profit organizations that are really active in trying to give access to art and the tools to make art or engage with STEM. But for the student who maybe has bumped into this article, or bumped into this conversation, or similar conversations, because they’re already engaging with game design and media, I would heavily recommend engaging with the free resources that are already available.

And so, if that first hurdle is a laptop, or the hardware to be able to produce games, that means navigating to a library or another environment that hopefully can offer at least the base level to be able to utilize software such as Unity or Blender — both of which being available for free. And then certainly tapping in with a lot of the YouTube tutorials, but also communities that are celebrating these conversations in a very big way. I think of an organization that I’m a part of, Black Voices in Gaming, where we already reach out on social media often to connect with the indie developers who are creating new projects and maybe just breaking out into that social space.

This interview has been edited for language and clarity.

Onsen Master is available on Xbox consoles, Nintendo Switch and PC (Steam/Epic Games Store).

February is Black History Month, an annual observance of the legacies of Black communities in Canada, the U.S., and other countries. More information can be found here. Some relevant initiatives to check out include Mynno, a diversity-focused Canadian gaming organization, Black creators promoted by Xbox and the women-led diversity group, Paidia Gaming.