Ubisoft and Riot Games have announced a new partnership on a research project that aims to help curb harmful player interactions in gaming.

The initiative, dubbed ‘Zero Harm in Comms,’ aims to collect in-game data that can be used to better train AI-based solutions to address toxic game chats. According to a 2021 study by game development platform Unity, 68 percent of players say they’ve experienced some form of toxic behaviour while gaming, which includes, but is not limited to, “sexual harassment, hate speech, threats of violence [and] doxing.”

Ubisoft, the French publisher behind franchises like Assassin’s Creed and Rainbow Six, and the U.S.’ Riot, best known for League of Legends and Valorant, are both members of the Fair Play Alliance, an international coalition of game companies aiming to improve in-game conduct for all players. As part of those efforts, Zero Harm in Comms intends to create a database that can be shared across the industry and implemented by companies into their respective games.

To learn more about Zero Harm in Comms, MobileSyrup sat down with the two guiding forces behind the project: Yves Jacquier, executive director at Ubisoft’s La Forge research division, and Wesley Kerr, head of technology research at Riot Games. The pair explained how the partnership started, how Zero Harm in Comms will work, their efforts to maintain privacy during data collection and more.

Question: How did the partnership between Ubisoft and Riot first come about?

Rainbow Six Siege (Image credit: Ubisoft)

Yves Jacquier: It all started with discussions between Wesley and I. We’ve been working separately on such topics of trying to identify toxic contents in chats, in communications, in general. And basically, we had R&D discussions acknowledging that it’s a very complex problem, and that it’s a problem that we would be way more efficient to tackle together. But there is a lot of difficulties to goal — questions such as, how do you share data between two different companies while obviously preserving the privacy and confidentiality for our players? And being compliant with things such as GDPR [Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation], for example? And then, on top of that, how do you create efficient AI to really understand the intention of chat lines to be able to make a recommendation? So we thought that because it’s a complex problem, and it’s an industry-wide problem, we thought that our two R&D departments should partner into a common R&D project.

Q: Can you explain the research project a bit more? How does it work and how will it assist with AI-based moderation tools?

Jacquier: Let’s take a step back. Here is how the chat moderation interval works. You send some contents, a chat line, and then behind that, you have tools that are able to predict whether it’s natural, it’s positive, or it’s harmful content. The problem with the technologies that you can find from the shelf is that, most of the time, it’s based on dictionaries. So you have a long list of profanities that you don’t want to see in a chat. But the problem is that it’s very easy for players to bypass that. You can be very creative at spelling thousands of different ways of certain profanities. And on top of that, you can have new words, new slang, that come out of the communities.

So the idea here is twofold. First, try to find a way to gather enough examples of chats with labelled data. So being able to say that ‘this line is considered neutral,’ ‘that one is considered racist,’ for example, and with these data sets, be able to use that to train an AI with all those examples. So that when there is new content, the AI can make a prediction that this new content is either classified as neutral, racist, and so forth. So that’s really the idea.

Then the question is, ‘how will it have an impact on the player?’ This is way too early to tell, in reality. Because first, we need to make sure that we’re able to create these datasets, which is already very complex. If you want to do something [with] data, which is on the one hand valuable, while preserving privacy and confidentiality… And then it’s an extremely complex problem to try to get the general meaning of a sentence to make a prediction. So you have both a notion of reliability, which means what’s the percentage of harmful content you’re able to detect on the one hand — we want that to be very high. But by the same token, you want to have as few false positives that you that can have. You don’t want to tag an acceptable line as being a profanity, for example. So, before we are able to have clear ideas on that, it’s difficult to know exactly how it gonna directly work into our pipelines.

Q: What does the collaboration look like between Ubisoft and Riot? What’s the back-and-forth look like? Are you working with any external consultants to help bring the project together?

Wesley Kerr: So in this case, we’re starting just collaboration between the Ubisoft and [Riot]. There are at least two phases to the project — we’re in the first phase where we’re trying to identify what data we can share, how we can share it safely to preserve the privacy of our players, and then sort of work towards gathering those datasets that we can share between us and build that central dataset. So that process involves deciding how we want to label the datasets. And then we’re sort of following the framework provided by the Fair Play Alliance to discuss how we we label disruptive behaviours in comms. And then we take our labeled data, we scrub it of any PII [personal identifiable information] to make sure that we are compliant with the most stringent GDPR, etc, those legal risks, and then we take that label data, we put it into a shared place and then we move on to the next phase where we actually start building the models that [Jacquier] mentioned. And then once we start building the models, we see how well we can do. That will probably provide additional signals for what data we need to go gather, collect and iterate there to improve the models until we reach sort of the end of the project, which we scheduled to be around July, where we can talk more broadly about the results of what we’re able to achieve during this shared project.

Jacquier: I would simply add on that: let’s keep in mind that it’s R&D projects, so we take it like that. And we found that we have similar mindsets, in terms of our two teams, which helps a lot when you try to tackle this kind of issue. Which is why we’re not involving consultants — we’re trying to put the best people that we have in both our R&D teams to try to pave the way and create the first learnings that we’ll be able to share next July.

Q: You both touched on the idea of privacy, which is an important subject. Of course, this is still early phases and it’s an R&D project so things are in flux, but what steps will you be taking to ensure that players privacy is being maintained?

Kerr: We’re working to make sure that the only data that we share has all personal identifying information removed. And so we’re using different tools, internally built and off the shelf, to detect those sorts of things and remove them from our datasets. We are also only collecting the bare minimum that we need in order to make progress on that problem, which is sort of why I highlighted that iterative approach. So we’re starting with as little data that we can share as possible. And then we’ll add more if we think it’s needed to improve the models. We’re not just sharing everything carte blanche. And then we will only keep it for as long as necessary and protected each as if it were our own so to ensure that the privacy is there.

Jacquier: I think that covers anything. Also, we’re not specialists of GDPR, right? We’re data scientists, researchers, so we got support from the people who helped us to ensure our compliance as well in what we can do and what we can’t do. So we want to make sure that if we want to ensure player safety, it starts there. It starts by making sure that at the very inception of the project, we do not try to reinvent the wheel. But we try, conversely, to make sure that we are conservative in terms of data information about the player that we have to share, just like [Kerr] mentioned; we want to be to have the the lowest footprint as possible, while making sure we have a very efficient AI at the end of the project.

Q: A key reason you’re doing this it to crack down on toxicity in games, which unfortunately happens a lot. Some players just sort of accept that it’s something that happens, but obviously, we can still do more to try to fix that. As game makers, why is it important for you both to do something like Zero Harm in Comms?

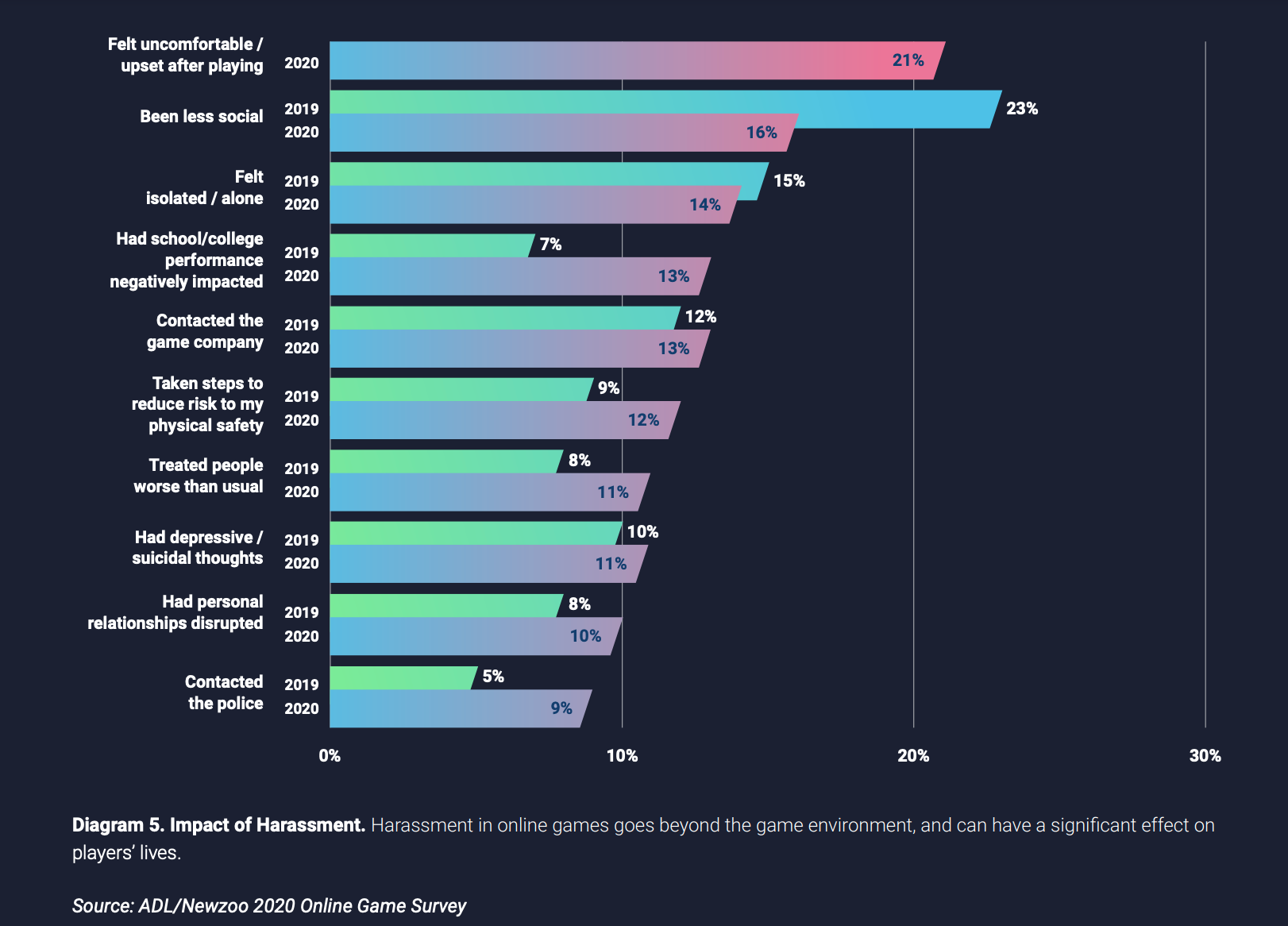

Data from the analytics firm Newzoo, cited by the Fair Play Alliance, that outlines the effects of harassment in games.

Jacquier: I think both Riot and Ubisoft are trying to create the best experience for players. So obviously, there are things that we do not control at all, which is what happens on public forums, for examples, external forums. There’s a thing that we somewhat control, which is the gameplay and the metagame, and whatever happens inside the game itself. And then there is what we want to improve, which is the flow of communication between players, and making sure that we have to acknowledge some players might not behave the way we want them to behave. There’s not much we can do directly on that, except, because we have zero tolerance on that, to try to make sure that we are first able to detect such harmful content, and then be able to create consequences, or to send a clear signal and educate all players in that. But it has to be fun for everybody and it cannot be fun if it’s not safe.

Kerr: I think the only thing we would add is we do aspire to be an industry leader in providing players with safe gaming environments in both client and game experience. We’ve taken lots of different approaches to this. It’s not just this one area. We’ve looked at names, we’ve looked at intentional feeding [when a player purposely dies to help the other team] and leaving… We’ve looked at lots of different ways to try to improve that player experience. This is one more push at that and I think internally, we’ve also built out a dedicated player dynamics discipline that’s looking at the punishment side, as well as the positive side of play. So how do we reward positive play and punish negative disruptive behaviour? And so all of that goes into sort of why why this investment is being made up.

Q: As you said, this is an iterative process — the first step of an early research project. Once you share the findings next July, what are you hoping to achieve in the next step as you open this up to industry partners?

Jacquier: It will depend on the results in terms of blueprints first. If we are able to create these blueprints, then we can start working together in terms of AI, and then it will be easier to imagine what the next steps are. So it’s really what we’re focusing on right now. But because we acknowledge that it’s a complex problem — so complex that most of the time it’s difficult, industry-wide, to go beyond recommendations, to go beyond trying to share good intent on that — if you want to be practical, we need to provide with some sort of practical blueprint. It has to be easy to share data. It has to be safe to share data. And then we are confident that we have find a decent blueprint that assures both sides that it’s easy and it’s totally safe in terms of privacy and confidentiality, then, and only then, we will be able to add new new people to to help in this endeavour. So whatever we’ve learned, we will share that in July. And based on what we’ve learned, we’ll be able to decide on the next steps.

Q: Zero Harm in Comms is trying to handle people in the midst of communication. What sorts of other steps do you think should be taken by the industry at large, not just Ubisoft and Riot, to improve behaviour from gamers before they even start playing? Because Zero Harm in Comms aims to react to that, which is a good step, but what can be done on a larger scale to reduce those sorts of toxic mentalities?

Jacquier: I cannot speak for other companies. All I can say is that for Ubisoft and obviously Riot as well, it’s a very important topic. We’re definitely not claiming that we have the perfect solution to solving this problem. What we’re trying to do is, based on the type of games that we have, the different kinds of communities and games that we are operating, we’re trying to find a common practical solution to solve one key aspect. But in reality, once again, it will be one tool in our toolbox, and the toolbox at Ubisoft is different from the toolbox at Riot. However, the intention of Ubisoft seems to be extremely aligned with Riot’s intention to have zero tolerance on that. So the recipe might be different, but as an industry and even beyond the gaming industry, we need to do something to make sure that we keep the online space safe for anyone.

Kerr: The only thing I’d add to that is our ability to work with partners in and out of industry to share the knowledge and grow our solutions to the complex problems that [Jacquier] has alluded to is going to not only impact our players, but everyone online, because people can take those recipes of what we’ve learned and bring them to their own players in their own communities.

This interview has been edited for language and clarity.

Image credit: Ubisoft/Riot

It should be noted that both companies have been accused of fostering toxic work cultures. At Ubisoft, there were numerous reports of misconduct, especially towards women, that started coming out in 2020. Company CEO Yves Guillemot apologized and promised change, which so far has included terminating a number of accused employees, hosting awareness workshops and appointing a VP of diversity and inclusion. However, employee advocacy group A Better Ubisoft said in September that progress has been “painfully slow” and a number of the alleged abusers remain at the company.

Riot, meanwhile, will pay $100 million to more than 1,000 women as part of a 2018 gender discrimination lawsuit. The lawsuit came about following an investigative piece by Kotaku in which many women accused male employees of grooming, sending explicit images and senior staff sharing a list of which women they wanted to sleep with, among other transgressions. In August, several employees told The Washington Post that significant cultural improvements have been made, although some criticism was levelled at mixed messaging regarding social media policies and diversity efforts.