Just over a week ago, Google announced its latest Chromebook. Built with the goal of reducing power consumption, heat, size and price, the laptop shocked many with its $249 price. Like many of its straight-for-the-heartstrings marketing strategies, the tagline associated with the ARM-based notebook is “the Chromebook for everyone.” To many, it is true: we live in the browser, and Chrome has proven to be a most capable vehicle. Add to that the many apps, native, and otherwise, available in the Chrome Store, and you’ve got yourself a pretty capable machine for under $300.

Yesterday’s announcement of the Nexus 4 has taken a page out of the Chromebook, um, book. Indeed, the LG-built phone could be called “the phone for everyone.” Priced at just $309CDN for the 8GB model and $359 for the 16GB version, the Nexus 4 is by far the most powerful device available to Canadians under $400. The equivalent LG Optimus G, by comparison, which uses mostly the same internals, retails for over $200 more outright. Of course, most Optimus Gs will be sold, subsidized, through the carrier, a practice Canadians are far more accustomed to.

When the Nexus One debuted in early 2010, it was touted as a developer phone. Google sold it through direct channels, and while it was an admirable device for the time, its $529 price ensured a relatively small market share. Google reworked its Nexus strategy later that year, offering the follow-up Nexus S as a subsidized device through multiple Canadian carriers. Due to baseband limitations, two versions were offered: an AWS-compatible i9020t and a UMTS-capable i9020a. While the Nexus S was a great phone, it too lacked widespread adoption, and was never sold by Google directly throughout its life cycle.

Google never sold the Galaxy Nexus directly to Canadians. It took on a strange hybrid status, offered to customers overseas in the form of a pentaband yakju variant. In the United States, Verizon was the sole provider of the Galaxy Nexus for many months, offering a CDMA/LTE version dubbed “tuna”. Eventually, a GSM takju model was offered directly on Google Play for $349, but to many users it came too late. And what about Canada? We got the strange, carrier-influenced yakjuux, beholden more to Samsung than Google. It looked and acted the same as its yakju sibling but for one major flaw: it wasn’t updated directly by Google. Because Samsung controlled the rollout of its over-the-air updates, Canadians were often months behind their international counterparts.

With the Nexus 4, Google has taken back control, but many potential customers will be perturbed at the device’s lack of LTE capabilities. While this is rightfully disappointing, there are a number of reasons Google omitted this important feature, and many of them are out of its control.

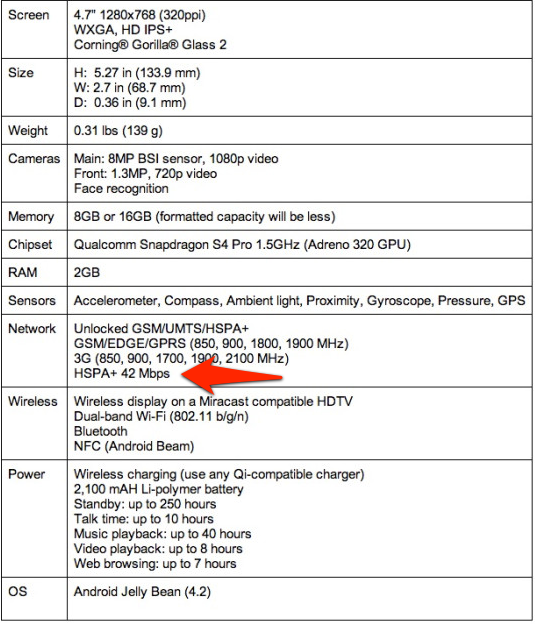

The Verge spoke to Andy Rubin upon the device’s launch, who cited two major reasons for not providing LTE support in the Nexus 4. The first reason is battery life: the Nexus 4 employs a quad-core Qualcomm Snapdragon S4 Pro SoC with a very high-performing graphics processor. Due to the chip’s die size, the baseband must be a separate low-power chip. In other words, it increases energy output inside the device. While both the CPU and baseband chips are manufactured using an energy-efficient 28nm process, the upshot is higher power consumption than the equivalent dual-core Snapdragon S4 SoC which, due to its relatively smaller size, consolidates CPU and baseband.

Of course, the LG Optimus G does have LTE support and initial testing suggests that battery life is not greatly affected. So there must be another reason, right? Rubin’s second justification is perhaps more contentious, but also more important. Cost and carrier interoperability. LTE networks are deployed in such diverse ways that most North American phones are not cross-compatible with those in Europe and Asia.

Rogers, Bell and TELUS employ Band 17 for LTE, also known as AWS frequency (1700/2100Mhz). Next year, once the 700Mhz spectrum is auctioned off by the Canadian government, they will add Band 4 to that list. That combination is used today by AT&T, while Verizon calls on just the 700Mhz spectrum to power its LTE network. But Verizon, like Sprint, relies on aging CDMA technology for its voice service, precluding unlocked GSM devices from being added to their networks.

Overseas, carriers use combinations of 800, 1800, 2300 and 2600Mhz in their LTE rollouts. In other words, the situation is a bit of a mess and isn’t likely to get any more sensible until companies like Qualcomm build chips capable of carrying five or more LTE signals on a single chip. Currently that limit is three. Apple found itself facing the same problem when it rolled out the LTE-capable iPhone 5: the North American GSM version uses Band 4 and 17, while the Verizon and international models use the more sprawling Bands 1, 3, 5, 13, 25.

Google faced such a carrier clustermuck when it decided whether to include LTE in the Nexus 4. In order to keep costs to a minimum, it has built one model capable of reaching the 3G networks in over 200 countries. These frequencies are ones that any modest tech geek will recognize: 850/900/1700/1900/2100Mhz. A phone with such abilities will work on almost every network in the world; just purchase a local SIM in your visiting country, and you’re good to go.

In order to equalize the situation somewhat, Google has ensured that the Nexus 4 supports DC-HSPA+ up to 42Mbps. This means that on carriers supporting the Dual-Carrier MIMO protocol — in Canada, that’s Bell and TELUS — users will be able to reach real-world speeds in the upper teens. On the excellent Samsung Galaxy II X, for example, I often surpassed 12Mbps down and 6Mbps up in Toronto.

There are other considerations here, too, ones that Rubin would unlikely admit to. While most carriers allow unlocked devices on their LTE networks without explicit registration, they do require OEMs to submit software for review when sold through retail channels. This is why the Canadian Galaxy Nexus was slower to receive updates: carriers had to give Samsung the go-ahead to push out the update. While they had less oversight over the process, carrier intervention is unavoidable when contracts are at stake. Google likely couldn’t work with every LTE-capable carrier to ensure optimal performance over their networks. HSPA+ networks, on the other hand, are mature and relatively universal.

The realization that the Nexus 4 lacks LTE may indeed be a deal-breaker for many North American users, but Google is confident that the benefits of a single, universal SKU outweigh the disadvantages. And when considering you can purchase the phone directly from Google — which guarantees expedited updates and a clean, smooth Android experience — one can see the appeal.

And there’s always the possibility of Google releasing a LTE model in a few months. Then it really would be “the phone for everyone.”