Last week, Google announced that it will shut down Stadia, its cloud-based gaming platform, on January 18th, 2023.

For many, it was hardly a surprise. After all, Google has long held a reputation for killing several of its products and services, and its apparent lack of commitment to Stadia — including its decision to close down its first-party game development division before it released a single game — certainly didn’t help matters.

Stadia players, find an important update on Stadia here: https://t.co/IIFRYiIYUu

— Stadia ☁️🎮 (@GoogleStadia) September 29, 2022

Naturally, then, this made Stadia a big punching bag of the industry, especially as both Google and Stadia’s fanbase insisted everything was fine. Indeed, when I wrote about this in January, I received more inflammatory responses than I had for anything else I’ve written, be it gamer entitlement, gatekeeking, criticism of PlayStation or the whole controversy surrounding J.K. Rowling and Hogwarts Legacy. While every platform has its toxic fans, I was surprised it was Stadia, of all things, that got me the most flack.

But I’m not here to say “I told you so” to all of my haters, nor am I looking to celebrate Stadia’s death. On the contrary — I wish things turned out differently. First and foremost, I’m certainly not happy about the employees and developers who were blindsided by this news, especially those who were still making games and features for the platform. Some of them don’t even know if they’re going to get paid, and that’s awful. I’m also all for giving consumers more choices, and Stadia did just that.

“So, here’s to Stadia: a technologically impressive, extremely mismanaged and utterly fascinating gaming platform.”

And even as I’ve been critical of the platform, I’ve also acknowledged its strengths. The core technology is sound, the controller is solid, and the ability to game without dedicated hardware is convenient. Moreover, I’ve always been a big proponent of streaming, and I’ve praised both Xbox and PlayStation for their measured approaches to the technology. But that was all let down by Stadia’s inherently flawed conceit as a platform centred around streaming games you predominantly had to buy à la carte. It banked on people being content with a platform that only allowed you to stream, in a market in which streaming is still novel. Xbox and PlayStation, meanwhile, give you the ability to stream, download or use physical discs. Even Nvidia GeForce Now, a cloud-only platform, lets you stream games you’ve purchased from other storefronts, which expands its catalogue significantly beyond Stadia’s relatively meagre library.

Google Shuts Down Stadia, Shocking Gamers Who Assumed They’d Already Done Thathttps://t.co/YLuxum52uH

— Hard Drive (@HardDriveMag) September 29, 2022

Stadia’s core foundation, however, is something I hope people build on. “We see clear opportunities to apply this technology across other parts of Google like YouTube, Google Play, and our Augmented Reality (AR) efforts — as well as make it available to our industry partners, which aligns with where we see the future of gaming headed,” Stadia boss Phil Harrison — a perplexing man who continues to fail at every company he’s worked for — wrote in a blog post about Stadia’s demise. I don’t have a lot of faith about how Google might salvage some of Stadia’s tech under Harrison, but I’d love to be wrong. In any case, the potential is there. I’ve said it before, but I always think back to hypothetical Stadia use cases proposed by Canadian games producer and former Stadia exec Jade Raymond, which include Stadia-powered interactive YouTube documentaries or Duplex-boosted NPC dialogue. It’s that sort of out-of-the-box, cross-platform thinking that could be truly innovative.

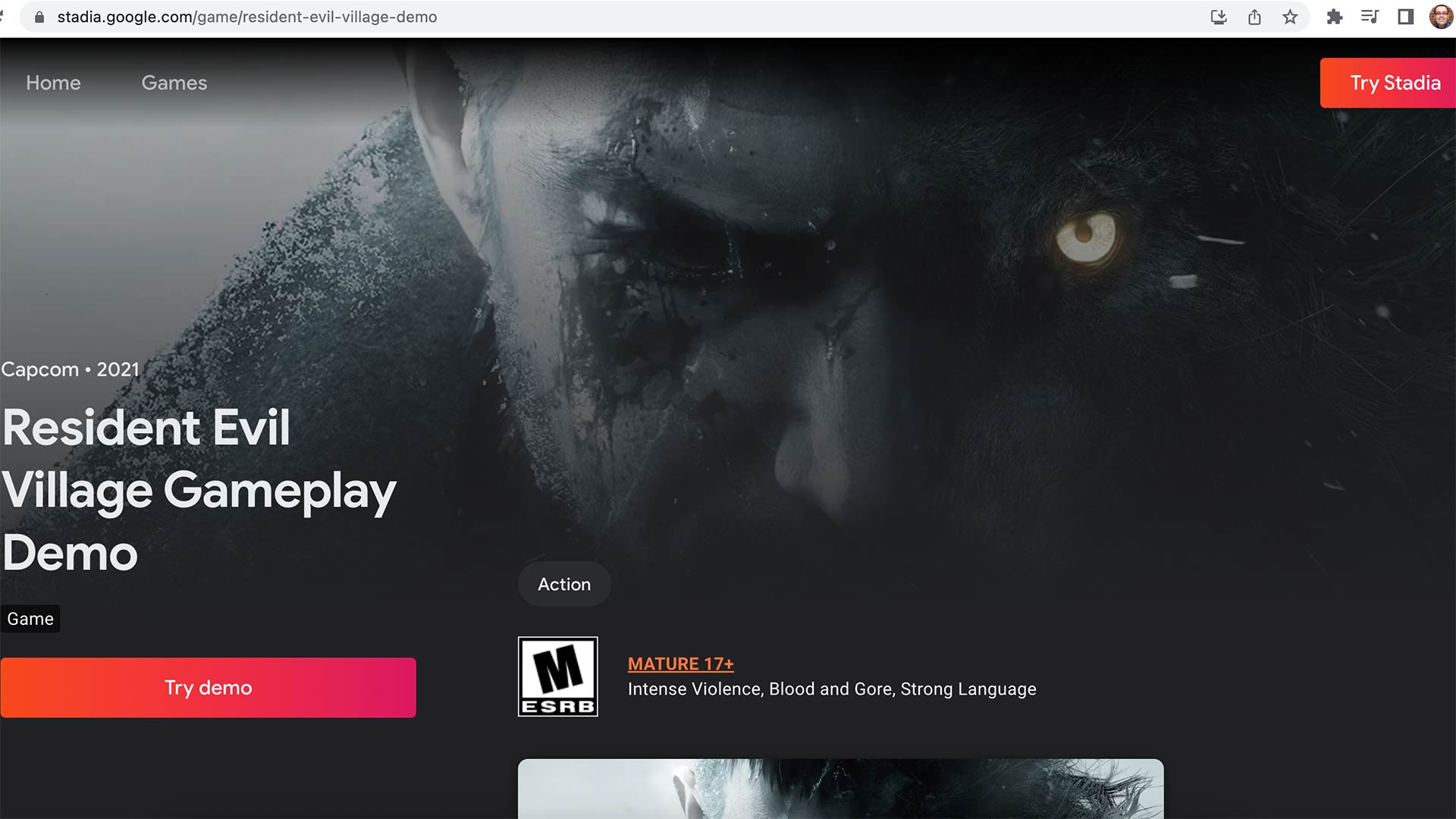

But even if Google itself doesn’t want to do anything itself with Stadia, I hope it continues to use the tech to help other companies. It’s already been selling Stadia tech to companies like Capcom, which has rather cleverly used it to let people stream a Resident Evil Village demo from their browsers. That’s to say nothing of developers like Bungie that found Stadia’s infrastructure to be an asset during remote development amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidently, Stadia doesn’t have to be a gaming platform itself to actually achieve success. Google refocusing its Stadia efforts on licensing and other partnerships, rather than selling games themselves, makes much more sense. A big reason why events like the Game Developers Conference are so important is that they give game makers a chance to share knowledge, and, in turn, help the broader industry, and hopefully, Google can do something similar with Stadia. A rising tide, as they say, lifts all boats.

Being able to play a demo for a big game like Resident Evil Village right out of a browser is wickedly cool. Image credit: Google

This is all just for the foreseeable future, too, mind you. As more companies push towards streaming and the technology continues to improve, it’s easy to envision cloud-based platforms becoming heavily adopted. In fact, we’re already seeing that happen. Newzoo, a reputable analytics firm, just published a report detailing how the games industry is set to generate approximately $2.4 billion USD (about $3.3 billion CAD) in cloud revenue this year.

On the one hand, that’s not much when you consider it’s set to make an estimated $200 billion USD (about $274 billion CAD) this year, which shows the market’s clearly not where Google wanted it to be for Stadia. But it’s also a 74 percent increase year-over-year, and represents about 31.7 million consumers paying for cloud gaming. Therefore, it’s in companies’ best interest to further invest in this space, and learning from Stadia’s mistakes and leveraging its considerable technology will only help with that.

So, here’s to Stadia: a technologically impressive, extremely mismanaged and utterly fascinating gaming platform. There’s never quite been anything like it, for better and worse, and hopefully, it can help pave the way for better offerings.