A federal court has agreed to hear an appeal by Bell regarding a decision the CRTC, Canada’s telecom regulator, issued last year.

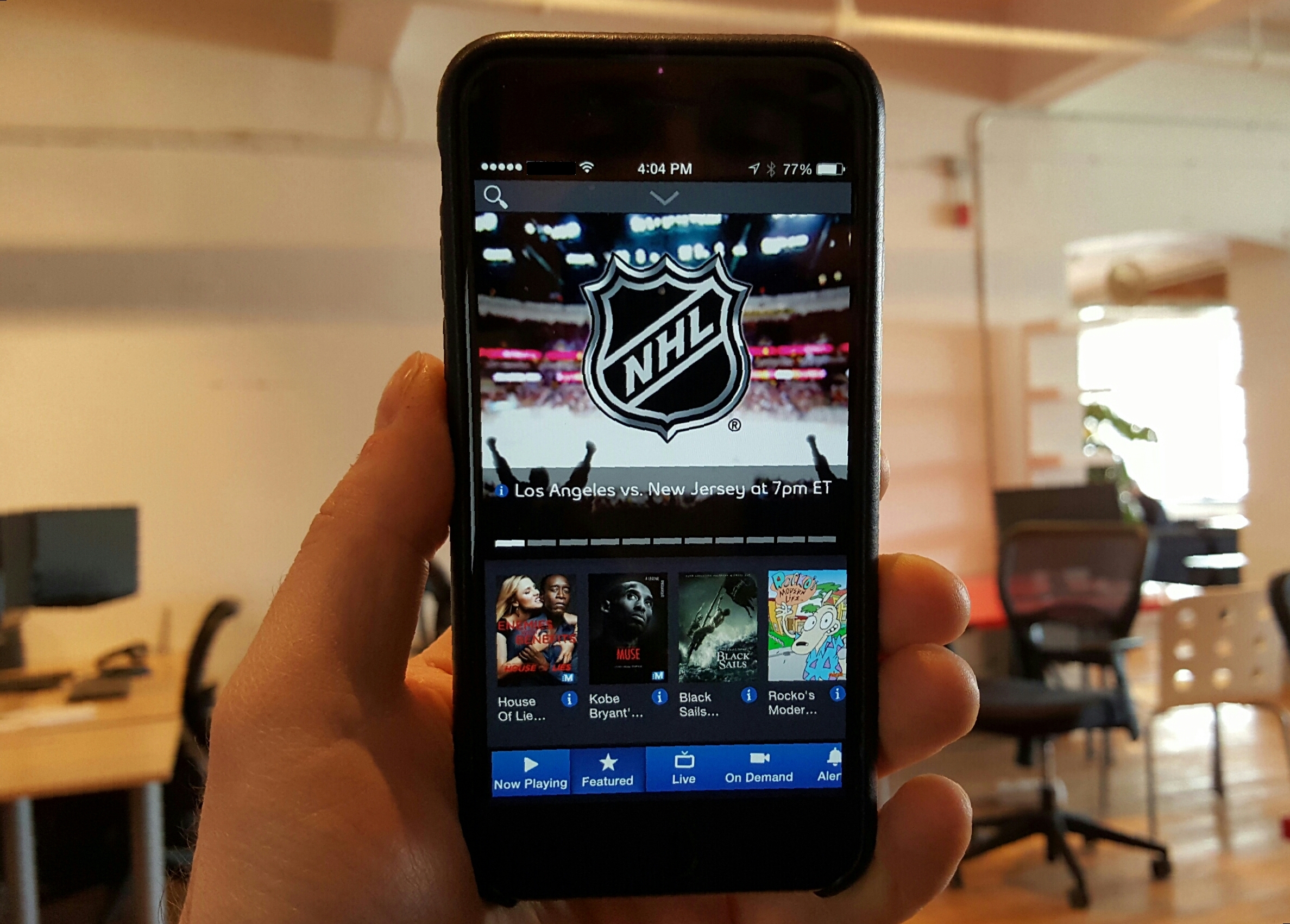

At stake is the definition of what constitutes a common carrier for television broadcasts, and whether, by preventing Bell from exempting its Mobile TV app from mobile subscribers’ data buckets, the CRTC has limited innovation among Canada’s vertically-integrated telecom companies.

Just under a year ago, the CRTC found that Bell showed its mobile TV service ‘undue preference’ by exempting bandwidth used by the service towards a customer’s monthly bill. Under the Telecommunications Act, such a move would count as “zero rating,” which undermines the idea of all network traffic being treated equally by a common carrier — in this case, Bell Mobility.

But Bell took the CRTC to court, arguing that its Mobile TV service should be regulated under the Broadcast Act, which has no such net neutrality stipulations. This week, that court agreed to hear the argument, though it is not expected to rule until closer to mid-year.

In those introductory hearings, Bell’s lawyers reiterated what the company has been saying for months: that mobile TV, as it sees it, is a mere resubmission of what constitutes regular television content — that is, strictly speaking, the same content one would access through a regular cable, satellite or IPTV subscription. That one has to download an app, from either the Google Play Store or Apple’s iTunes, has no bearing on whether it functions as a conduit for broadcasting, according to the company.

Even with that logic, the CRTC and its supporters say Bell used its position as a common wireless carrier to preference not only its own customers, but by virtue of the company’s media properties, its own content, when broadcasting mobile TV, violating the Telecommunications Act.

During the hearing yesterday, the Attorney General of Canada made the distinction between Bell’s actions as a carrier and as a broadcaster, saying that the regulator was right to penalize the telco, since the issue was not with the content, which is determined by the Broadcasting Act, but the fact that Bell knew it was treating the traffic itself — that is, the ones and zeroes — differently for its customers than those of its competitors.

Regulators in both Canada and the U.S. have kept a keen eye on what vertically-integrated telecom companies have been doing recently. Last month, the T-Mobile, the third-largest carrier in the States, defended its BingeOn service, which exempts certain video feeds from counting towards customer monthly data allotments, saying that it was an optional service and did not unduly preference any particular video provider.

“Binge On is a VERY ‘pro’ net neutrality capability,” said John Legere, T-Mobile’s CEO, in a blog post. “You can turn it on and off in your MyTMobile (sic) account – whenever you want. Turn it on and off at will. Customers are in control. Not T-Mobile. Not content providers. Customers. At all times.” And though the FCC has repeatedly said that it will protect the rights of internet users through the Title II classification of the Communications Act, it has heretofore not found anything impermissible about T-Mobile’s zero-rating strategy, since the company does not own the audio or video content that passes through its network facilities.

In Canada, Quebec’s Videotron has undertaken a similar service for audio, Unlimited Music. Under the program, data generated by streaming music services Spotify, Google Play Music, 8tracks and Deezer doesn’t count towards a customer’s monthly data pool, but critics have said that by entering into deals with only the largest, often U.S.-centric, companies, Videotron disadvantages nascent startups that have less brand recognition.

For Bell, the narrow scope of the CRTC’s ruling, which is meant to keep in check vertically integrated corporations, is a blow to Canadian innovation. The telco has said that after the decision was passed that it was forced to raise prices on its Mobile TV add-on, from $5 to $8 per month, since it is now less attractive to the average wireless customer. The company has said that services like Mobile TV (in its ideal form) will go a long way to competing with international behemoths like Netflix, which this week announced that it now has 75 million customers.